03 January 2009

The Light at the End

By July of 1969, Rex had completed his home leave, picked up the ends of his family life, and was back on the job as on the Federal Compound in Suitland, Maryland. Two years of preparation in Hawaii, and a year in sweltering Saigon had riveted his attention on a foe who was implacable, though apparently not invincible.

Harnessing all the tools of gained in his career, he could be justly be proud of his contributions to stabilizing a desperate situation, and then taking the initiative to the enemy.

Focused as he was, perhaps it is not surprising that the changes back home were disorienting in the extreme. His son, Earl Junior, told me something about that.

“The paradox of Dad being so "old school" while being under the tutelage of such a young Turk (as Bud Zumwalt) is interesting. As is true of most people, Dad did become substantially more conservative with age, and what happened in Viet Nam certainly had a profound impact on increasing that effect. I think it was Churchill who said that a man who is not a liberal as a youth, has no heart, and a man who is not a conservative at age, has no mind.”

There is another way to say it, of course, which is that a social progressive is a person who has not been mugged yet, and the city of Washington had been beaten up badly.

The Washington Rex had known when he left for the gentler climes of Pearl Harbor in 1966 had been destroyed by an event as profound, in its way, as the Tet Offensive of 1968 had been. They were only separated by months, after all, like the assassination of JFK and President Diem of the Republic of Vietnam.

When Rex left Washington, support for the war in Asia was general, if being questioned. The massive insertion of American ground forces provided, in the words of General Westmoreland, “light at the end of the tunnel.”

Tet had undermined that confidence on the battlefield of Vietnam, and U.S. combat deaths mounted with the scale of operations, as they are to a lesser degree in Afghanistan today. Before Rex’s arrival, those who perished in Vietnam were mostly professional soldiers and volunteers. From 1966 on, they increasingly were ordinary citizens and draftees: kids from next door, or right down the block. At the end of 1965, the total of American KIA was 636; not unlike that of the early phases of Operation IRAQI FREEDOM.

By the end of 1967, the number had risen to 16,021, four times the number of dead who so galvanized protests against the military intervention in Iraq, and less than a quarter of those who would ultimately die, including Jack Graf.

We are a phlegmatic bunch in uniform, and have a curious phrase that conveys certainly based on experience. It begins like this: “There is no doubt in my military mind….” and continues with whatever observation of a fundamental truth has been discerned. In Rex’s military mind, there was no question that progress had been made in the Vietnam War, and he was right.

SEALORDS was hurting the Communists were being hurt: their casualties far outnumbered those of the U.S. and ARVN, their main force units had been driven deep into base areas along the Laotian and Cambodian borders, far from the centers of population they had sought to occupy in the Tet campaign. By mid-1967 U.S. air power was doing serious damage to the North Vietnamese infiltration net and infrastructure.

A parallel civilian offensive to SEALORDS was being implemented throughout Vietnam; the Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support Program (CORDS) was not unlike the concept of today’s Provincial Reconstruction Teams in Iraq. Rural pacification began to make headway against the Viet Cong, hamlet by hamlet.

(Pentagon Protest 1967)

In anyone’s military mind, this was progress. But Tet had changed the calculus and America writ large has no “military mind,” nor does it wish one. Watching Walter Cronkeit on evening news each night, the horror of combat was splashed directly onto their TV dinners. On 21 October, 1967, some 50,000 anti-war demonstrators ringed the Pentagon.

Something else had changed while Rex was away tending to the nation’s needs. Washington died. The murder of Dr. King at the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis had unleashed a fury that made America begin to reconsider its own conventional wisdom.

As word of Dr. King's murder spread on the evening of Thursday, April 4, 1968, crowds began to gather at 14th and U.

(Stokely Carmichael, 1968)

Charismatic Stokely Carmichael, Howard University graduate and former head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), led members of that organization to visit storekeepers in NE DC, demanding they close out of respect to Dr. King’s memory. Civility declined rapidly, and by nightfall widespread looting and arson began.

The grim quip at the time was that the organization that Carmichael now led was the “Non-Student Violent Coordinating Committee,” but there was little laughter to spare to go around.

The violence wasn’t just in Washington, of course. Thirty other cities commenced their own immolation of central cities. Ash fell like snow on cars parked in Pentagon North Parking. The District’s police (3,100 strong) were overwhelmed by tens of thousands of rioters.

President Johnson dispatched some 13,600 federal troops, including 1,750 federalized D.C. National Guard troops to restore order. Marines mounted machine guns on the steps of the Capitol and Army troops from the Old Guard (3rd Infantry) guarded the White House as rioters reached Farragut Square.

By the time the city was considered “pacified,” on Sunday, April 8, twelve citizens of the capital had been killed, 1,097 injured, and over 6,100 arrested. Additionally, some 1,200 buildings had been burned, including over 900 stores. Damages reached $27 million, which taken in constant dollars, is something closer to $200 million today.

(Aftermath of the Washington Riots, 1968. Newsweek Photo- Leffler)

The riots utterly devastated Washington's inner city economy, and the territory north of the official city became terra incognita. That is the Washington that I knew when I first came to town to observe the massive protest against the incursion into Cambodia on May Day 1970.

It was downright creepy. Magnificent Union Station was dark, and the way from the street to the tracks under the great vaulted dome was channeled by white plywood barriers to keep travelers away from the pools of rainwater on the marble floors.

You can understand that Rex, and a lot of people took a dim view of what had happened to their country while they were away. But he was a professional officer, and there still was a war on. In response to rising unpopularity, the Military District of Washington decreed that uniforms were no longer required for duty days in the Pentagon, Wednesdays, and active duty personnel were encouraged to change into them at the office.

And of course the war ground on. In 1966, more than 200,000 troops were committed to Vietnam, but the number had mushroomed to at peak of 543,000 troops in April 1969.

Despite metrics that suggested progress was being made, the Navy was in a pickle. It was not only running an aggressive unilateral offensive campaign in the Mekong Delta, but also supporting operations elsewhere along the extensive coastline. Warships provided lavish gunfire support to Army and Marine units in contact with the enemy, and close air support fro the Carriers on Yankee and Dixie Stations, north and south in the South China Sea.

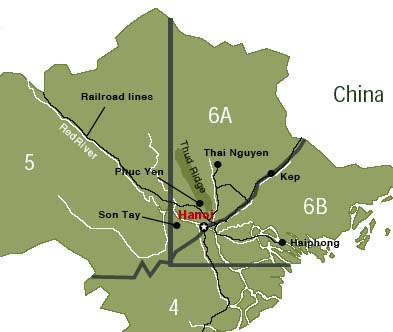

(Route Pack Exclusive Air Operations Routes Over North Vietnam)

Controlling the Air War was an increasing problem. Theater Commander Admiral implemented a scheme called the “Route Pack system” to de-conflict air operations over North Vietnam. The system divided responsibility within North Vietnam into seven different geographic areas, with the Air Force and the Navy each receiving responsibility for portions of the route packs, quite independent of one another. The entities involved were wildly diverse: CINCPACFLT (Carrier aviation), the Air Force’s Seventh (Vietnam) and Thirteenth (Thailand) Numbered Air Forces, and independent sub-unified Strategic Air Command.

(SECSTATE Dean Rusk, LBJ, and SECDEF Robert McNamara, in the Cabinet Room. January 20, 1967. Photo credit: Yoichi R. Okamoto)

There was not comprehensive means to conduct coordinated post-strike assessments, and the targeting process was further complicated by this patchwork of responsibility. Targets were selected in Washington by a small team on the Joint Staff and approved only at the Presidential level. The memory of LBJ on his hands and knees in the Oval Office reviewing target graphics is one that strikes fear into anyone’s military mind.

But in the words of a later Secretary of Defense, you fight the war with the military you have. The Navy did the best it could to answer two critical questions that remained after every airstrike and every fire mission: Did you hit anything worthwhile? Was there collateral damage to friendly or civilian targets?

There was no feedback from the supported units ashore. Sometimes A-1 Skyraider prop aircraft like my Dad flew would provide observer services with binoculars. They were marvelous airplanes and courageous pilots, but prone to a certain subjectivity. Like body-counts, the results were often inflated in significance. (“Great Secondaries!”)

Rex had been ordered back to DC as Intelligence Collection Division Chief, responsible, inter alia, for the Operations Coordination Branch. That activity, headed up by LCDR Charlie Peterson, was responsible for establishing priorities for nominations to the collection decks of the service, theater and national technical sensors.

On 22 August 1969, a staff study on the advisability of the establishment of a collections operations management plot (Navy lingo for watch center, or COMP) was commissioned.

Rex was the man with the most recent experience in the ground war, the sensors available, and the vision to understand what was required by the operational forces.

The survey worked around the clock and delivered a positive report by 05 September recommending establishment of the COMP.

(The Hoffman Center, Alexandria, Virginia)

Two weeks later, the COMP was established in Room 5D718 in the Pentagon, a space now demolished in the reconstruction of the grand old building. Two months later, the whole operation was relocated to the grim Hoffman Building near the approaches to the Woodrow Wilson Bridge in Alexandria.

This whole business had the net effect of raising Rex’s eyes up from the tactical imperatives of Vietnam to the global dance with the Main Adversary whose proxies in Vietnam had caused such distraction.

The Defense Intelligence Agency was widely viewed as being slow on processing Navy Specific Intelligence Collection Requirements (SICRs) which resulted in critical missed opportunities to gain insight into exactly what the Soviets had been up to in the massive worldwide naval operation “OKEAN 70.” The deployment signaled the arrival of the Soviets as a global player on the blue water, and panic for the service that had just completed a transition to brown-water combat.

VDM Bud Zumwalt left SEALORDS behind and became Chief of Naval Operations in July of 1970, and his challenges were manifold. He confronted a service where racial tension in the Fleet resulted in near-mutiny situations. The brown-water war in Vietnam had to be stabilized and transformed into a Vietnamese effort. The Russians were afloat, and increasingly aggressive.

He needed help in transforming his Navy to meet the new threat. He had an idea where he could find men he could trust. His first Z-gram (properly known as a Z-NavOp #1) became effective on 14 July.

Based on strong sustained performance afloat and ashore, Rex was selected for flag on the one star-board in calendar 1970 for promotion in FY-91. Zumwalt was impatient to get on with the transformation. There was still a war on, after all, and maybe more than that.

Rex was frocked to RADM (lower half) in 1971. Admiral Zumwalt had his quirk and he was quite ruthless in getting what he wanted. One of the tactics he employed to ensure that his legacy would survive was to ensure that every flag officer with a lower lineal number (date of commissioning) than his was off active duty before he ended his tenure as CNO.

That was how Rex got his number, and his next major challenge, but I will have to tell you more about that tomorrow. Frankly, this is all a little overwhelming to take so new in a fresh decade. The wind outside is howling, so cold that it burns.

Copyright 2010 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Subscribe to the RSS feed!