04 February 2011

The Price of Bread

(Lieutenant Khalid Islambouli attacks President Sadat, 06 Oct 1981.)

It is the day that some are calling the Friday of Departure for Hosni Mubarak. I guess the Egyptian Army will be the arbiter of that, but I can’t tell from the balcony at Big Pink and won't try.

Yesterday I sketched in broad detail the career of Anwar Sadat, the President of Egypt who was shot down by a jihadi-inspired junior officer in 1981. I got a mild sprinkling of questions about why I was wasting time with ancient history, but there is a method in my madness. So slice up some nice seven-grain bread for morning toast, slather some fresh creamery butter on it, or maybe some Pond Hill Farm jam and pour some coffee.

One thing about taking things slowly is that I did not know that an old service buddy was actually there in the crowd when President Sadat was gunned down.

My pal was traveling in the official entourage of Lt. Gen. Bob “Barbwire” Kingston, commander of the US Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force (RDJTF), ancestor to the US Central Command that manages our military affairs in the Middle East.

(General "Barbwire" Bob Kingston, 1984. Official US Army photo.)

A small group of officers from the command were on hand to honor President Sadat at the 1981 Military Parade commemorating the Egyptian crossing of the Suez Canal in 1973. My pal was sitting with the General and his aide next to the VIPs stand when Lieutenant Islambouli charged, spraying the distinguished attendees with his AK-47 as he came.

Barbwire Bob’s aide was a Marine Major who thought fast in the hail of gunfire. He pulled the general down, covering him with his body and took a round in the thigh, shattering the femur. The wound resulted in the award of the Navy/Marine Corps Medal and a medical discharge for the Major.

That vignette occurred in an ancient place, a city with five millennia of history and drama as its heritage. One aspect I did not mention has particular bearing on the tale of unrest, both old and new. It is the price of bread.

After the Yom Kippur War, President Sadat waged a charm offensive in the US. He courted senior Christian religious figures such as the Pope and Billy Graham in a successful attempt to humanize himself with American voters. His visit to Israel in 1977 earned him a Nobel Peace Prize along with the wrath of the Arab Street. But his celebrity in the West could not conceal his problems at home.

The same year he visited Tel Aviv, there were bread riots in Cairo. Sadat tolerated no dissent on the home front, and like Nasser before him, never put himself before the citizens in a fair and open election. With the Canal closed for eight years and no oil to export, his public policy options were limited. His economic policy was termed the “infitah,” which in Arabic literally means “open door.”

After the 1973 war, Sadat began relaxing government controls on the economy. In this way, he hoped to encourage the private sector and stimulate foreign investment. Part of that liberalization, coupled with the strictures of an austere budget, meant deep cuts to government subsidies to foodstuffs.

The reduction of flour, rice, and cooking oil subsidies triggered the bread riots of 1977. Sadat was forced to re-institute the subsidies, trapped between the rioters who wanted more food and the IMF who wanted their loans paid back.

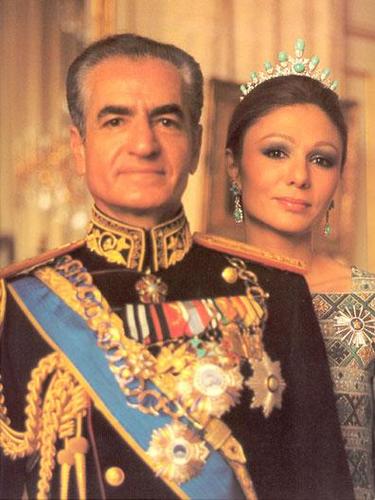

(Mohammad Rez? Sh?h Pahlavi, Shah of Shahs and wife H.I.M Farah, Empress of Iran. Official photo.)

Did I mention that the Shah of Iran was a good pal of Mr. Sadat? He made his first stop in Egypt after abdicating his throne, and spent his last days in Cairo, after a stay in the US for medical treatment that infuriated the new Islamic government of Iran, and may have provoked the storming of the US embassy in Tehran.

The Shah returned to Egypt in March 1980, where he ultimately died from complications of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. President Sadat gave the Shah a state funeral, with internment in the historic Al Rifa’i Mosque. The last royal rulers of two monarchies are buried there, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi of Iran and King Farouk of Egypt, his former brother-in-law. I have no idea if they will continue to rest there when the new regime establishes itself.

(Tomb of the Shah of Iran in Cairo. Photo Ahmad Badr.)

Hosni Mubarak kept to the Sadat agenda of pragmatic peace with Israel and vague support for the American agenda in the Middle East. He survived six assassination attempts along the way, and got a big payday from George H. W. Bush in 1991. The American President forgave twenty billion dollars in Egyptian debt in exchange for support to Operation DESERT STORM.

By then, Mubarak was able to play the stability card as the anchor to peace. The West was more than willing to overlook the repression that went along his Mubarak’s rule in exchange.

The global financial crisis orchestrated by the Too Big To Fail crowd on Wall Street had major ripples across the world. We focus on our problems here, naturally enough. But the economic slow-down hit Egypt hard, just as it did Tunisia. There was a triple whammy of consequences: high unemployment, rampant food inflation and low wages.

And that is where we get to the heart of the matter. I will not try to dissect the tactical picture on the ground this morning. Al Jazeera can help you better with that. But according to people who are supposed to know these things, World food prices reached the highest level ever recorded in January of this young year, and will keep rising for months.

The untold story behind the turmoil in Tunisia and Egypt and the rest of the Arab world is the pressure on the working poor and underemployed. Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and Hosni Mubarak are just the first leaders who have felt the ire of their people.

They are not going to be the last.

Regrettably, I have to be a hundred-odd miles down the road this morning for a meeting, and will have to leave it at that for now. But tomorrow we will take a stroll through what is going to affect us all soon enough.

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

vicsocotra.com | Subscribe to the RSS feed!