29 August 2007

After the War

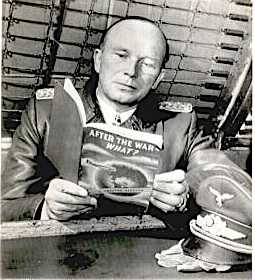

(AP) General Ulrich Kessler does some light reading on U-234, 1945

Unterseeboot 234 (U-234) was a Type XB submarine, configured by the German Navy to carry loads of mines for covert emplacement in the approaches to Allied ports. She was big and slow, which were not useful qualities in the last days of the Reich. She could carry heavy cargo, though, and that was precisely was required as the Red Army invested Berlin, and the Allied armies halted their advance to await the fall of the German capital.

U-234's Captain was Johann “Dynamite” Fehler, a veteran of the surface raider Atlantis, and his instructions were to run silent and on the schnorkel enroute Japan.

His mission was to covertly carry 240 metric tons of German weapons technology to the Empire of the Rising Sun. Lieutenant Commanders Hideo Tomonaga and Genzo Shoji of the Imperial Japanese Navy had scoured the Reich for projects that might help defeat the Allies in the Pacific at the eleventh hour.

They had found enriched uranium, and advanced fuzes for artillery shells, and jet fighters. They had been assisted by their German hosts, beginning the great sweepstakes for the products of Hitler's weapons labs.

General Leslie Grove, chief of the Manhattan Project, had been suspicious about the German bomb project for a good reason, and the Japanese were most interested in The Bomb as a means to escape the noose.

There are many curious happenstances in the last voyage of the U-234. There are those who darkly intimate that there was a plot to cut a deal with the Allies for the escape of senior Nazi officials. There are those who believe that the precious cargo of secrets was never intended to arrive in Japan, but to be transferred as a bribe better than gold.

The end of a war is a messy business, equal in magnitude to the messiness of conducting it. The cloud of confusion and secrecy is impossible to unravel now with any authority; certainly the U-boat was carrying a number of passengers that makes the destination of Japan plausible. That, of course, would be the hallmark of a good cover story in the looking-glass world.

In addition to the Emperor's men, there was the air contingent headed by Luftwaffe General Ulrich Kessler, designated liaison officer to Tokyo. Supporting him was 1st Lt Erich Menzel, a radar specialist, and Lt Col Fritz von Sandrart, an expert in antiaircraft defenses. Gerhard Falcke, a naval construction expert with diplomatic experience, headed the naval delegation. Heinrich Hellendorn, a naval antiaircraft specialist, claimed to be intent on studying the Imperial Navy's tactics at sea. Richard Bulla, a naval aviator, had been sent to observe Japanese carrier naval aviation. Naval Judge Advocate Kay Nieschiling was to be in charge of military justice for the two thousand Kriegsmarine personnel in Japan. August Bringewald, who headed a two-man Messerschmitt contingent, was in charge of ME-262 jet-fighter production. Franz Ruf, an industrial machinery specialist, was to help the Japanese build new aircraft factories.

Dr. Heinz Schlicke, one of Germany's leading electronics experts, was to help Japan develop new radar and countermeasures systems.

Surfacing after darkness on 10 May 1945, Captain Fehlen learned that Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz was now the acting Fuhrer of the Germans, and that he had signed the documents of unconditional surrender to the Allies. He directed his U-boats to proceed to the nearest Allied port to surrender. Fehlen could have returned to Europe; instead he decided to continue to North America.

Fehlen radioed Halifax, and announced his intention to surrender. The Japanese naval officer took overdoses of barbiturates, and were buried at sea with full honors. USS Sutton intercepted the German submarine on 14 May 1945, embarking a prize crew of fifteen Americans, and removing the Germans for processing as Enemy Prisoners of War.

General Kessler made something of a splash as he disembarked in his tall boots and officer's greatcoat with Iron Cross. The Associated Press staged a photo op with him reading a popular book of the day, “After the War.”

Dr. Schlicke was just another civilian in the crowd. After his initial publicity, General Kessler would return to Germany to testify about war atrocities before the Nuremberg Tribunal.

Dr. Schlike was headed for somewhere else altogether.

So was the cargo of the U-234. The enriched uranium vanished from the Navy manifest on arrival at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and two dismantled jet fighters that had been loaded in Germany were missing as well. It is possible that General Groves got the uranium, and it may have been shipped to Oak Ridge for processing in the weapons that were being readied for Japan.

Normally, the prisoners would have been destined for processing at the special EPW camp at Fort Hunt, Virginia, but there was nothing normal, not anymore. The War in Europe was over, and everything had changed.

Some claim that the infrared fuzes developed by Dr. Schilke provided the key to a tough problem the Los Alamos physicists could not solve: the simultaneous detonation of the spherical array required to trigger the implosion device used in the second A-bomb.

The truth might be in a box someplace in the Archives at College Park, Maryland. What is certain is that the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) interrogated the prisoners to determine the state of German experimental weaponry, and inventoried the storage compartments of the U-boat. ONI officers from the New York Naval District Office were stunned to find complete drawings and prints for the V-1 and V-2 rockets, a complete, disassembled ME-262 jet fighter, an ME-163 rocket-propelled fighter, and disassembled jet engines.

A V-2 rocket team was already in US custody, and they were not at Fort Hunt. They were living in a Washington hotel, and complaining about their per diem allowance.

The Navy realized that the most valuable reparation available from Germany could be the brains of its scientists. The various technical bureaus of the War Department began to show intense interest in acquiring the dedicated services of the German technical specialists.

Keeping them in comfort in hotels was clearly not the long-term solution. Accordingly, a castle was found to accommodate them, high on a bluff on the Long Island Gold Coast.

In 1946, the bulldozers completed the eradication of the PO Box 1142 at Fort Hunt. The whole camp disappeared as if it had never existed.

The program known as OVERCAST was compromised, and not surprisingly, the public was not ready for the idea that Nazi scientists were going to be working for Uncle Sam. Accordingly, the program was re-christened with a name as common as a postal box.

In 1946, Project PAPERCLIP got into high gear.

Copyright 2007 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Close Window