Operations Against Vicksburg

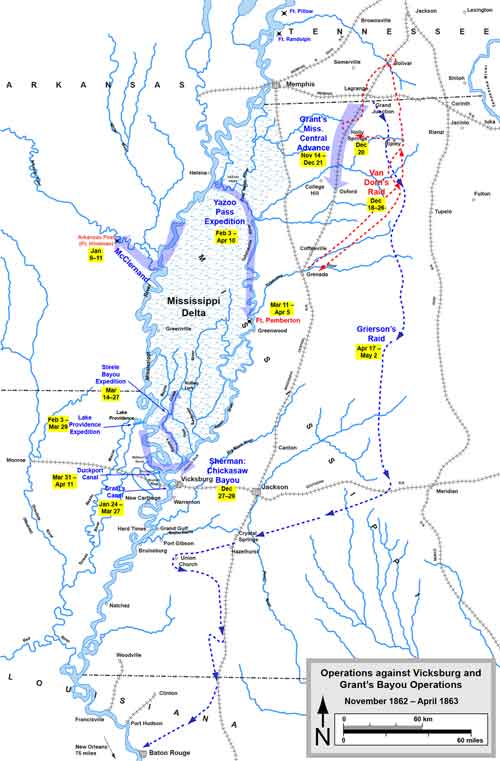

(This map tells it all. Vicksburg is in the middle- literally- just south of the great blob of the Mississippi Delta. Grant’s Bayou Operations are to the are to the west of the City, which commanded the Mississippi River. The trick was to get to the east and across the water so the Union could surround the City and bring it down, cut the South in half, and win the war in the West. Map drawn in Adobe Illustrator CS5 by Hal Jespersen, property USG).

I was looking around for something that would help me understand some details on the exploits of GG Uncle and Grandfather, the men who would become brother (in law) before this sweeping war was over. Two Irish lads caught up in something quite remarkable, the scope of which had never been seen in North America before, and the like of which had never been seen in this world.

The story is, perforce, jumbled. I was on the field at Raymond last month with a good pal- he is back there again, caring for some family business, and I feel a tug to go and see the places where my kin walked and got shot at.

So, having taken Uncle Patrick up the moment of his capture at Raymond, and having covered his escape from captivity before, now we are plowing the ground of the 72nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, where Grandfather drove a team of horses when he was not raising a rifle against his future in-laws.

To further confound the narrative, I realized that the detailed genealogy that Mom had compiled in December of 1963 would be useful, since it would cover the terrain from Ireland to Nashville for Patrick, and from the Auld Sod to the valley of the Ohio River for Grandfather.

I despaired of that, since I have no idea where the ring-binder I have kept since childhood might be. It certainly is not in Arlington. But in the course of doing something else, I found the document on the external back-up drive of a computer I use at the farm. Huzzah! There is too much to discuss about all that- and who cares about the 1934 All-American Quarterback at the University of Pittsburgh, anyway? (Miller Munjas, btw, but there is no time for that now!)

Anyway, to help you through this chaotic passage, we are in November of 1862. Patrick is now on an intensively personal journey as a fugitive that we have discussed before, heading back to Nashville in a circuitous manner without sanction of the Confederate Army, and under wary gaze of occupying Federal forces.

James is with the 72nd OVI, and the unit history places them in Grant’s Central Mississippi Campaign, conducting operations on the Mississippi Central Railroad, November 2, 1862 to January 12, 1863. Then there is a period of duty at White’s Station through March 13, and then ordered to Memphis before being directed to proceed to Young’s Point, La.

As we discussed yesterday, it was all about Vicksburg. The map sums it all up. We will have to talk about Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton presently, the man who commanded the garrison of that citadel town on the river. Grant’s operations to capture the city consist of a dizzying amalgamation of what we would call today joint operations- naval support, infantry maneuver, failed engineering initiatives of amazing scope and eleven distinct battles from December 26, 1862, to July 4, 1863.

Smart people who are not following their family around the various battlefields divide the campaign in two. The first part, which we are talking about today, is termed “Operations Against Vicksburg” (December 1862 — January 1863) and the second par t “Grant’s Operations Against Vicksburg” (March–July 1863).

Grant initially planned a two-pronged approach in which half of his army, under Tecumseh Sherman would advance to the Yazoo River and attempt to reach Vicksburg from the northeast, while Grant took the remainder of the army down the Mississippi Central Railroad. That is the strand where Grandfather James would have marched. Both of these initiatives failed. Grant conducted a number of “experiments” or expeditions that attempted to enable amphibious access to the Mississippi south of Vicksburg’s artillery batteries.

All five of these initiatives failed as well. Finally, Union gunboats and troop transport boats ran past the batteries at Vicksburg and met up with Grant’s men who had marched overland in Louisiana. That included the 72nd OVI, which was at Young’s Point, LA, a major Union supply depot and trans-shipping point throughout the Vicksburg Campaign.

On April 29 and April 30, 1863, Grant’s army crossed the Mississippi and landed at Bruinsburg, MS, marking the beginning of the Battle of Port Gibson. When his 17,000 troops began landing the sole witness to the invasion was a farmer who appeared too confused to flee. The port proved to have a good solid bank, and space for many boats. It was the largest amphibious operation in American military history until D-Day.

We will get to what happened after that presently, but here is how Grant put the accomplishment in his memoirs:

“When this was accomplished I felt a degree of relief scarcely ever equaled since. Vicksburg was not yet taken it is true…but, I was on dry ground on the same side of the river with the enemy.”

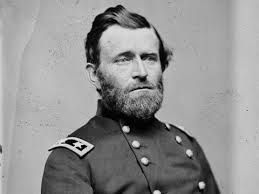

He was a stubborn son of a bitch, no kidding.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socota

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

High and Dry

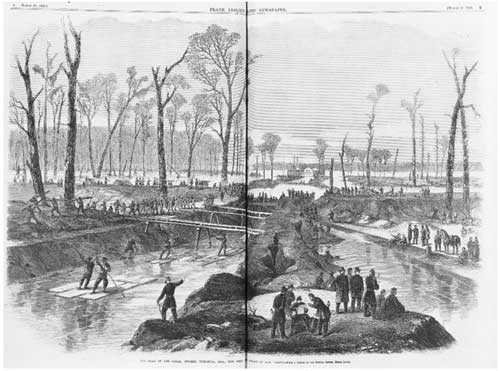

(William’s Canal- later Grant’s- on the De Soto Peninsula near Vicksburg, MS.)

There is little possibility that either Great-Great Uncle Patrick or Great-Great Grandfather James ever saw Major General Earl Van Dorn in the flesh, though they certainly were not far away from one another. In fact, we are coming to a place in the sprawling geography of the civil war in which they were all tantalizingly close to one another.

Van Dorn’s greatest victory might have been at a place that both my relatives knew intimately: Holly Springs. There was a lot going on in the Mississippi Delta country in the winter and spring of 1862-63.

Hell of a legacy, really. Van Dorn was at the bottom of his class at West Point, and had secured an appointment to the Academy because his mother was a niece of Andrew Jackson. He had a successful career in the pre-war Army, and a good showing in the Mexican War and subsequent action against the Empire of the Summer Moon in Texas against the Comanche warriors.

(Colorful Major General Earl Van Dorn in uniform).

Van Dorn got mixed reviews in his conduct as a Confederate officer, though. Dashing and generally successful as a leader of cavalry, he did not appear to have the head to manage large combined forces, or command of logistics. It was the latter that did him in at the Battle of Pea Ridge, in early March of 1862 out in Arkansas when he split his forces and left his baggage train behind in an attempt to get behind the union forces assigned to Brigadier General Samuel R. Curtis.

His men were hungry by the time they arrived in what had been the Union rear, and Curtis had realigned his forces and repulsed the Confederates. That was the beginning of the collapse of the Confederacy west of the Mississippi, but the key to it all was Vicksburg, the last Rebel citadel on the River. Van Dorn was brought back from Arkansas and directed to commence operations to stop Grant’s operations against the last remaining stronghold on the Mississippi. As a field commander, he got whipped at Second Corinth, but in December, he made a daring raid on Grant’s winter Headquarters at Holly Springs, capturing 1,500 Union troops and destroying a Union logistics hub valued a $1.5 million dollars. The raid only delayed Grant a while, who was busy on projects of his own.

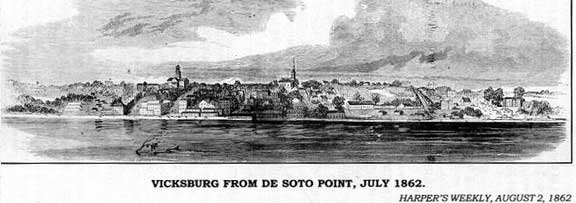

Vicksburg was strategically vital objective for the Spring. Jefferson Davis declared: “Vicksburg is the nail head that holds the South’s two halves together.” President Lincoln knew it, too. During one meeting at the White House, he stated his strategic vision: “…Vicksburg is the key. The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.”

It was the only place where the Confederates still held onto railways running east and west, and it blocked Union transit down the river from North to South. Under control from Richmond, the city blocked Union navigation down the Mississippi; together with control of the mouth of the Red River and Port to the south, it permitted transit with Arkansas and Texas, desperately needed to provide soldiers, horses and cattle.

Vicksburg was known as the “Gibraltar of the Confederacy” because of its natural defenses. The geography was perfect for defense. The Mississippi curled around the De Soto Peninsula on which the city sat, and Rebel guns were positioned to rake any steamships attempting to run by them. North and east of Vicksburg was the Delta of the Mississippi a complex network of interconnected streams and rivers nearly two hundred miles long and fifty miles wide. Even when things dried out in the summer, it was nearly impassible. In the rainy season in which the 72nd OVI waited in Memphis for the offensive to commence, it was literally a quagmire.

And there was the matter of the climate. The winter of 1862-63 was a wet one and all the waterways and bayous were up. The intimidating appearance of the defenses of the inland Gibraltar led to some out-of-the-box thinking. Remember the Bridge to Nowhere up in Alaska?

U.S. Grant had a breathtaking scheme. Why didn’t he just move the Mississippi?

A year earlier, when Union troops made the first attempt to capture Vicksburg, Gen. Thomas Williams began digging a three-mile-long canal across DeSoto Point. He planned on using the canal to bypass the city, but it was never completed. Grant decided to complete the canal and then cut the upstream levee. Engineers assured him that “a wall of water would roar through the ditch and scour out an entirely new channel. Within days the river would shift approximately two miles west of Vicksburg.” If Grant couldn’t capture the city, he would simply make it irrelevant by moving the river.

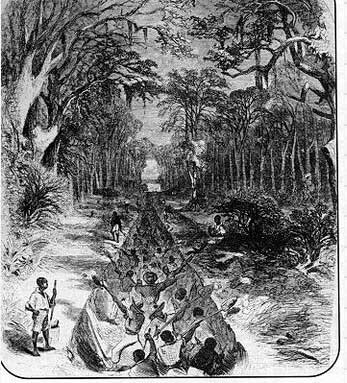

Professor Terry L. Jones of the University of Louisiana put it this way: “Put in charge of connecting the upper end of the canal to the river, Tecumseh Sherman made an inspection and was shocked to find that Williams’s effort was “no bigger than a plantation ditch.” Nonetheless, he began the work with the men of his 15th Corps and an unknown number of slaves confiscated from area plantations.

Continuous rains plagued the workers and caused the flood waters to rise higher. Sherman complained in one letter: “Rain, rain — water above, below and all around. I have been soused under water by my horse falling in a hole and got a good ducking yesterday where a horse could not go. No doubt they are chuckling over our helpless situation in Vicksburg.”

It was a mess. Men sickened in the miasma, and as many as twenty a day died between January and April. were buried in the levee where the corpses often washed out in the pelting rain. Meanwhile, the river was rapidly rising and the swamps disappeared under standing water and transportation on the roads was nearly impossible. I can only imagine the frustration of Grandfather James with his team of horses attempting to travel in the mud. Add the swarms of biting mosquitos and you have a picture of complete misery.

Steam-powered dredges were brought in to help finish the canal, but as Spring of 1863 arrived, the water was coming down, leaving only a foot of water in the canal and barges and boats were left high and dry and abandoned. The press was calling for Grant’s removal.

By late January, Grant concluded that the canal at DeSoto Point would not work. When the flood waters finally receded in the spring, Grant abandoned the canals and marched his army downstream and the Vicksburg Campaign began in earnest.

Grant was roundly criticized for his canal projects, of which the one at De Soto Point was only one of several. The principle was sound, and the climate eventually cooperated to demonstrate that the idea was not crazy. Although the war was long over, the flood of 1876 cut a new channel across the point, not far from the path of Grant’s Canal, and left proud Vicksburg high and dry.

General Earl Van Dorn did not live to see any of it. He was shot in the back of his head by an outraged husband in May of 1863. Not by Yankee troops, but by Dr. James Bodie Peters. He claimed Van Dorn had carried on an affair with his wife, Jessie McKissack Peters. Van Dorn was writing at his desk at his headquarters at Spring Hill when Peters entered the room unannounced and and blew the back of his head off.

It was in May of 1863, when the war in the West was taking a decisive turn imposed by the implacable will of Ulysses Simpson Grant. Van Dorn was the senior Major General in the Confederate Army at the time, and his death cost the service a “useful leader at a critical juncture of the Vicksburg campaign.”

Not that there were not some more interesting events along the way, and the future brothers-in-law in my family were going to be high and dry to see it in person.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

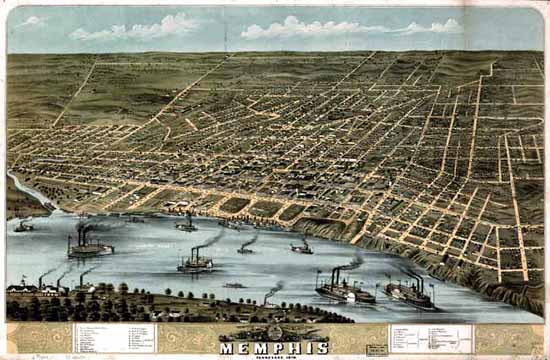

Memphis

The 72nd OVI wearily trudged into Memphis at the end of July, 1862. I am hoping that part of the long journey was via the railcars of the Memphis and LaGrange Railroad, but that space was often reserved for the mounds of munitions and supplies necessary to keep thousands of men in the field.

In the city itself, the population was deeply suspicious of the Yankee military occupation, and there were still many armed men in the countryside who were potential threats to the public order.

As with any occupying force, there is unease, but no real combat. Life in garrison is infinitely preferable to life in a bivouac, after all. The 72nd conducted presence and patrol operations through November as Grant planned to take Vicksburg to the south.

What was life like for the troops? I have nothing from Grandfather, certainly nothing as colorful as the fantastic recollections of Uncle Patrick, who was not far away, but a letter from Captain Charles. W. Brouse, company K, 100th Indiana, to his parents, from the same period (January written from Grand Junction, Tennessee, which is about 40 miles south of Memphis) contains some glimmer of the common experience for the troops:

“On the following Sabbath, at 2 p.m., we were ordered to march immediately, and we marched ten miles that evening by 9 o’clock and camped ten miles south of Holly Springs. Leaving at daylight next morning, we arrived at Holly Springs at noon….

On Monday, January 6th, we marched in a northeasterly direction to Salem, Miss., by 5 o’clock p. m., 16 miles, Major Parrott commanding the regiment. The next evening we camped at Smith’s Mills, where the same rebel force that attacked Holly Springs made an attack on us, but were repelled by one company of Hoosier boys…

We arrived at the Junction on the 10th inst., and camped on the north of the town on low ground. It had rained all day and the ground was very soft. About midnight it commenced raining in earnest and continued until morning. We were without tents. In company with my Lieutenant we had the fly belonging to the Major’s tent for a covering. About one p. m. the water made a break over the ditch around us, and in less time than it takes me to tell it the water was about three inches deep, entirely covering our blankets. You can imagine it was not very pleasant standing in the water pulling on our socks. — When I went to put on my boots they were half full of water. After dressing we stood in the rain the remainder of the night…

Our camp is on the east side of the railroad. We think our position is a good one. We have a block-house made of heavy logs; also a stockade, two bake ovens in which we bake all the light bread we want, and we have plenty to eat. We have just received our tents for the whole regiment, and hope never to be without them again. We have had hard marching, but little fighting…

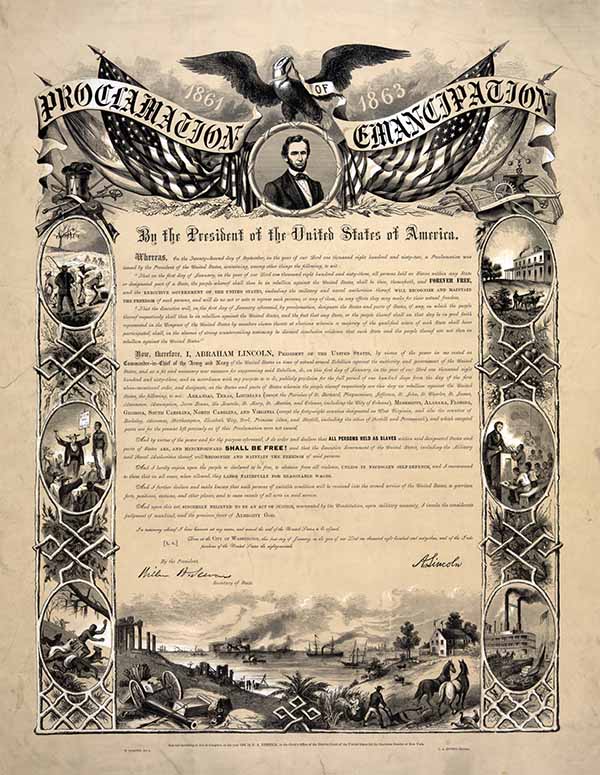

If you could see how this country is laid waste, houses and farms destroyed, it would make your heart ache, but as the boys say, it is all on account of rebellion. Write soon, and tell me how things are going on in the North; how the President’s proclamation is received by the people. It suits us much; we are ready and willing to return home and fight traitors there if it must be so. In this I think I speak the sentiment of almost the entire army.”

The address that Charles Brouse was talking about was the Emancipation Proclamation. Back in the East, at Antietam (or Sharpsburg, if you prefer) the bloodiest single day in American military history ended in a draw, but the Confederate retreat gave Abraham Lincoln the “victory” he desired before issuing the Proclamation that defined the aim of the War plainly and simply.

That was the way it was received by the troops in the field around Memphis, Tennessee, as the second full year of the war began with a new frame of reference. There would be a lot of it to come, and shortly as the 72nd OVI and the men of Grant’s Army moved out for Vicksburg.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

Occupied

Great-Great Grandfather James and his Service Buddies in the 72nd OVI were preparing to move out from their bivouac in front of Corinth. The Confederate decision to withdraw from the city, and leave the critical rail junction to the Federals had changed the calculus of the War in the West.

General Halleck was returned to Washington where “Old Brains” could shuffle paper in the burgeoning bureaucracy, and There was the matter of taking Vicksburg, and the sundering of the South into two pieces, with the Union controlling the Mississippi River from its headwaters to the Gulf of Mexico.

But in the meantime, there was territory that required occupation. Memphis had surrendered, but the imposition of Law and Order on hotbed of secession would require troops. The 72nd was directed to set out for the city on the first of June, via La-Grange, Grand Junction, and Holly Springs, TN.

Here is the situation they would find when they got there:

Memphis, Friday, June 13.

The city remains unusually quiet and orderly, and business is slowly reviving. Thus far, the amount of rebel property seized amounts to only $50,000.

Capt. Dill, of the Provost Guards, estimates the amount of cotton, sugar, &c., concealed for shipping, to be $150,000. This is rapidly finding its way to the

levee.

The number of absentees has been over-estimated. Many have returned, while those who go on upward boats are mostly members of sundered families.

The Mayor and City Council are of Union proclivities, as a general thing, and exercise their functions in harmony with military rule. Their continued good conduct is a renewed assurance of this.

There are only two or three places in the city where either Confederate scrip or Post-office stamps are worth anything. The most prominent rebel citizens will

not take the scrip.

Mr. Markland, agent of the Post-office Department, opened the City Post Office today, and an agent of the Treasury Department is on his way to open the Federal Custom-house.

There have been about thirty applications for the office of Postmaster, by prominent citizens of Memphis. There is, as yet, but one National flag flying from a private residence, and that is from the house of Mr. Gage.

There is but little activity in shipping, although a few dray loads of cotton have been hauled down to the levee this morning. Some 5,000 bales are concealed in warehouses.

The Avalanche, in an article on the belligerents, admits that the South has defended the use of privateer and guerrillas, and charges the North with the commission of crimes at which human nature, in its wildest paroxysms of passion, feels itself horrified. It claims that the legitimate belligerents should settle the questions of war, leaving peaceful civilians to the enjoyment of their rights, and observes that these views are acknowledged by the Federals here, and thinks that this course will win gradually upon the Southern people.

The Argus indulges in a series of rabid and vindictive articles, and should be suppressed at once.

The Avalanche says about 75 rebel officers and soldiers have thus far surrendered to Col. Fitch, the Provost Marshall.

The United States Navy Yard and buildings have been taken possession of by Flag-officer Davis in the name of the Government, and will be occupied as the headquarters of his fleet. The buildings are in good preservation.

The Memphis-Grenada Appeal, of the 10th, says that misapprehension prevails in regard to the Partisan Rangers. They are called into service by the Confederate Congress, and are designed to act beyond the lines of an army as independent fighters, to be provided like ordinary soldiers, and to have all they capture, yet the Appeal insists they are not guerrillas, and hopes the young men will not fear to enlist.

It says, “if the Federals treat them as pirates, President Davis will interfere to protect them”

The Appeal states the facts of the occupation tolerably fairly, admitting that

Col. Fitch is pursuing a system of liberal public policy, yet it indulges in vindictive comments.

Memphis, June 14.

Col. Slack issued orders this morning prohibiting dealing in and using the currency of the Confederate States, and that the use thereof as a circulating medium would be regarded as an insult to the Government of the United States. Persons offending are to be arrested and summarily dealt with.

*******

It looked like the presence of Grandfather and the Boys from Fremont, Ohio, were just what the city needed to help everyone stay calm, and collected in the occupied Volunteer State.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

Missing Memphis

The circuitous route of the 72nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry on their way from Corinth to Memphis, Tennessee, is a matter of some speculation. Their route of march would have put them in places where Yankees were not welcome- and also other places in the upper South that enthusiastically contributed troops to the Union cause.

It must have been curious for my Great-great grandfather and his comrades to troop along the sweltering dusty roads and not know what to expect from the inhabitants of the little hamlets between Corinth and La-Grange, Grand Junction and Holly Springs, TN.

Or the looks from the young men slouched on the porches of the rude homes or hanging around the railroad stations who just weeks before might have been Rebels on the tree line.

I have a line on getting access to some documents that might clear that up at the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center at Fremont, Ohio, and that is near my personal line of advance to the valleys of the Ohio River that set the course of my family’s history in the Civil War later in the summer. So I won’t worry about it just now.

The gentle late Spring of Culpeper captivated me at cocktail hour yesterday. The Russians have erected a pleasure pavilion in the wooden fenced enclosure that keeps the deer and the foxes at bay. The chicken tractor is established, with some pullets growing from yellow chicks to adolescent chickens in the blink of an eye, and the bustle of activity from five hives of happy bees.

It is an exceptional place to relax on a Memorial Day. It reminds an old Vet that there are things worth working for- and fighting for.

When I got back to the farm last night, I contemplated exactly that. It is a day for contemplation.

About this time of the year a long time ago the 72nd marched and sweated their way across Tennessee.

They missed the excitement at Memphis as they trudged toward the city in June and July of 1862. Thirteen miles a day they marched, on average. This is why they were ordered to do it: as a result of the Federal victory at Corinth, the railroads that linked Memphis with the eastern part of the Confederacy had been cut, severely reducing the strategic importance of the city.

Therefore, in early June, the Confederate cabinet in Richmond determined that Memphis and its protective forts had to be abandoned and left to the depredations of the Federals. That was to be the role of the 72nd: presence and occupation. The Confederate garrison of Bluff City was dispersed to join units elsewhere, including Vicksburg, and only a small rear guard was left to make an inconvenience to the Yankees.

The importance of the water lines of communication are a factor that the generations that travel by interstate cannot viscerally understand. There were two means of transit in those days that did not require the use of Shank’s Mare. Rail and River were the means that saved shoe-leather.

The Rebel River Defense Fleet defending Memphis would also have retreated to Vicksburg, but it could not get enough coal in Memphis to fire the boilers. Unable to flee when the Federal fleet appeared on June 6, the decision was left to a binary course of actions: fight, or scuttle the boats. They chose to fight, steaming out in the early morning to meet the advancing Union flotilla and the rams trailing behind it, with the citizens of Memphis cheering them on.

The steamboats were commercial in origin, modified by the addition of heavy timbers placed around the engineering spaces, and cotton bales stacked high to protect the firing positions. This defensive protection earned them the term “cotton-clads.” As they sortied out, the battle started with an exchange of gunfire at long range, the Federal gunboats setting up a line of battle across the river and firing their rear guns at the confederates coming up to meet them as they entered the battle, stern first.

(Line engraving published in Harper’s Weekly in 1862. Ships in the foreground are: Monarch (letter “M” between stacks), Queen of the West (with letter “Q”) and Lioness (letter “L”). In the left background are: Switzerland (with letter “S” on paddle box), Samson and Lancaster. Note cotton bales stacked on deck to protect boilers. Line engraving after a sketch by Alexander Simplot).

Maybe that is the best way to approach this battle of two largely amateur Navies. Three months before, the Department of War authorized the establishment of a flotilla of steam rams for employment on the Western Rivers. Several powerful river towboats were heavily reinforced for use as ramming ships.

Two of the four Federal rams advanced beyond the line of the gunboats and rammed or otherwise disrupted the movements of the Rebel combatants. The others, perhaps wisely, misinterpreted their orders and did not enter the battle at all. With the Federal rams and gunboats not coordinating their movements and the Confederate vessels operating independently, the battle soon was reduced to a melee.

It is agreed by all that the ram flagship USS Queen of the West collided with CSS Colonel Lovell, and then was rammed in turn by one or more of the remaining cotton-clads. The Union commander (and architect of the ram designs) was a hastily commissioned Col. Charles Ellet, who was quickly wounded by a pistol shot to his knee, thereby becoming the only casualty on the Union side.

The remainder of the battle is obscured by more than the fog of war. Several eyewitness accounts are available; unfortunately, they are mutually contradictory to a greater degree than usual. Great-Great Uncle Patrick would have approved of the story-telling. The after-action reporting generally agrees that at the end of it all but one of the cotton-clads were either destroyed or captured, and the Yankee flagship Queen of the West, was disabled.

The sole boat to escape was CSS General Earl Van Dorn, which made good for the protection of the Yazoo River north of Vicksburg. Personnel losses among the Confederates cannot be estimated reliably, and Colonel Ellet succumbed to measles contracted in the infirmary and was the only death for the Union forces.

The battle took less than two hours, and resulted in the immediate surrender of the city of Memphis to Federal authority by lunchtime.

The battle of Memphis was not quite the last battle on the Rivers, but it set the tone for the rest of the war. The ironclad CSS Arkansas would contest the Federal thrust down the Mississippi River against Vicksburg, but for now, the waters were ruled by the rag-tag Federal Fleet, augmented by the real Navy advancing upriver from New Orleans, commanded by the U.S navy’s first Rear Admiral, David Farragut. The river was now open down to Vicksburg, the key to the West. Grant would not be ready to move south until November, and until then, the South needed to be occupied.

And so the 72nd OVI marched to Memphis, arriving in late July. They would stay there until November, when Grant was ready to open the river all the way to New Orleans.

Despite the lopsided outcome, the Union Army failed to grasp its strategic significance.

The battle- one of only two entirely naval mass engagements in the war- represented the last time civilians with no prior military experience were permitted to command ships in combat. As such, it is a milestone in the development of professionalism in the United States Navy, and I applaud it. War at sea- or river- is no place for amateurs.

When the 72nd finally trudged into Memphis in late July, they were on “other duties as assigned,” and stayed in Bluff City until November of 1862. Then they were offered the opportunity to join Grant’s Central Mississippi Campaign.

Just kidding- they don’t call orders “invitations.” Off to see the elephant once more went the lads of the 72nd OVI and we will get to that story when we get to it.

Great-great Grandfather would start with operations on the Mississippi Central Railroad, and stay at it until January of 1863. A detailed appreciation for his time in Memphis will probably require a stop at Fremont, Ohio, where the 72nd was mustered in, and a vist to the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library.

It is going to be a rich summer indeed.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

Happy Memorial Day

I saw a Holiday note this morning that showed a prominent politician eating an ice-cream cone. The caption- it was from one of the parties, of course- wished me a “Happy Memorial Day.”

I have done the same thing- said the same words, though I don’t eat as much ice cream as I used to. I typed the phrase this morning and realized how truly appalling it is.

I go to Arlington on the Memorial Day weekend. I think it is important to pay a small tribute to those I knew in life, and that is the reason for the Holiday, after all. I have been writing a lot of stories about the Civil War. I am blessed to have had some colorful family members in that conflict, and who lived to tell their tales.

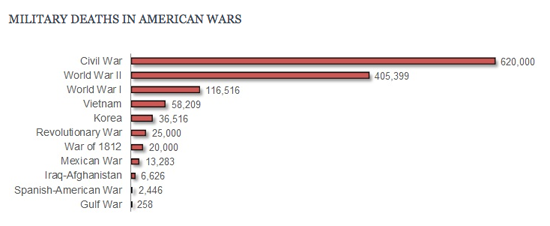

So many did not. So many, in fact, that the total number of military deaths in all other conflicts in which America has fought did not equal the number killed in the Civil War until late in the Vietnam conflict.

So, rather than be a grump about a holiday that has its roots in sorrow, but now is the unofficial commencement of summer, with leisure and pleasurable activities abounding, I try to keep my perspective and take flowers to Arlington National Cemetery.

There are a lot of other people who do the same thing.

Rolling Thunder is in town for the ride through the capital, and there were thousands and thousands of them packed with their motorcycles into Pentagon North Parking.

I snuck in the back gate, the one that opens into the controlled territory of Fort Myer to avoid the throng at the ceremonial entrance. I drove down the long slope, past all those stones: uniformly white, in crisp sight-lines and stupefying numbers.

I visited Vince and Dan first in Section 64, since the marches from the Old Post Chapel to the then-newly excavated graves were the saddest I have experienced.

Then Scotty, in Section 60, best damn fighter pilot who ever lived. His stone is up now, and I think he would have approved of it. They are letting the families put a phrase of remembrance on the stones now. I think that is a good thing, and I made a note to think about what to put on mine.

Finally section 66, and the resting place of a truly Great American: our pal Mac and his beloved wife Billie.

I gave all of them the best salute I can render these days, and left red carnations to brighten the pallor of the eternal stones.

I was comforted by it. And now I can relax, and have a happy weekend. I hope you do as well, but please, remember. We owe it to them.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

Quaker Guns and a First Class Clerk

(General Henry Wager Halleck, Union Commander in the West, 1862).

It is only about 24 miles from Pittsburg Landing to Corinth, MS, but it can seem a lot further. Maybe it is the state line. Maybe it is the guy in charge.

The front end of the War in the West features General Ulysses Grant as the victor at Fort Donelson and- barely- at the bloodbath of Shiloh. It is a little disconcerting to see him slip back in the hierarchy as the Union Armies of the Ohio and Tennessee Mississippi massed.

Grant, of course, had the Army of the Tennessee. But the magnitude of the force- some 120,000 strong- required an overall commander senior to Grant. That man was Henry Wager Halleck, a long-serving officer noted as a scholar and lawyer, two qualities that Grant would eschew. His Service Buddies called him “Old Brains,” due to his expertise in the doctrine of the military arts.

He was a cautious man, a shrewd property developer and a master of logistics. He believed in careful preparation, not bold acts.

He was above all things an able administrator, adept at administrivia. Later, as what we would call Army Chief of Staff in Washington, he was unable to exert effective influence on his field commander in the East, “Little Mac” McClellan. President Lincoln was exasperated by the lack of aggressiveness, and he disparaged Halleck as “little more than a first class clerk.”

At the end of the war he wound up as Chief of Staff to Grant, a man who had his flaws but knew what war was about when Lincoln selected him as General-in-Chief to scourge the Rebels. But that was later, and after a parade of Union Generals who were too timid or unlucky, and baffled by the risk-taking tactics of Robert E. Lee and his bold Lieutenants.

But my Great Great Grandfather and the 72nd OVI are subordinated to General William Tecumseh Sherman in the Army of the Tennessee , and probably not that concerned with General Halleck.

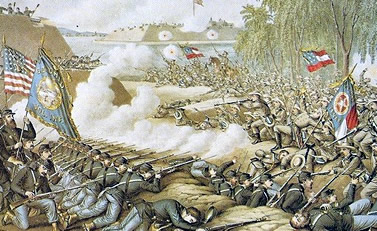

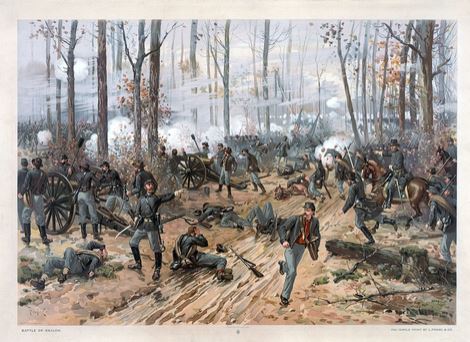

The results of the battle at Shiloh had everyone talking. With more than 20,000 casualties on the field, the whole notion of what the war was about was changing. The crowds that had taken picnic baskets to the field at First Manassas (Bull Run, if you prefer) were suddenly chilled at the magnitude of the violence that had been unleashed.

Halleck was extra cautious. He believed strongly in thorough preparations for battle- I see him from this distance as something like British Field Marshall Montgomery, for whom everything had to be “just so” to move forward. In the aftermath of the carnage at Shiloh, he was determined to follow Joe Johnson’s Confederate Army to the railroad junction at Corinth. Still, his caution leaned toward the value of defensive fortifications over quick, aggressive action.

Although Corinth would have been a single day’s march for Stonewall Jackson’s Rebel “foot cavalry,” Halleck presided over a tedious campaign of entrenching at each advance. By the end of May, he had succeeded in moving only five miles toward Mississippi. The weather was bad, and Halleck entrenched every night.

Eventually , there were seven progressive lines and forty miles of trenches along the way south from Shiloh.

I don’t know what Grandfather might have thought- the realization of the magnitude of the disasters that could happen obviously was as well known to rank and file Union soldiers.

On the other side, Confederate morale was low and General P.G. T. Beauregard’s force was outnumbered two to one. The water was polluted. Typhoid and dysentery rendered thousands of his troops non-combat ready or killed them outright. As the rest of the war would demonstrate, the hygiene of men in the ranks was appalling and deadly. Sickness had claimed as many men as had the fighting at Pittsburg Landing. At a high-level staff meeting, the Confederate officers concluded that they could not hold the rail junction at Corinth, and the best plan was to disengage from Halleck’s forces and withdraw toward Tupelo.

There was an action at Farmington, in which the always aggressive John Pope’s union troops made it almost to Corinth, but were ordered back to consolidate with General Don Carlos Buell’s Center Wing.

The fight at Russell’s House was the one featuring Sherman’s division, and the 72nd OVI. General James R. Chalmers had formed a strong defensive position, and Sherman proposed to hurl two brigades against them, supported by a third. On May 17 the attack commenced as the Confederates responded with a flank attack that nearly succeeded before Union field artillery from the 1st Illinois saved the day.

Widow Surratt’s Farm was contested on the 21st of May in a see-saw battle before the Confederates retired. On the 27th, the Double Log House (a stout cabin converted to a block-house with firing positions created by knocking the chinking out) was the objective for Sherman’s Division, and would have been supported by the 72nd OVI.

Sherman formed an attacking column with two brigades and two more in support. The Confederates rallied and drove Sherman’s skirmishers back, but the counterattack stalled against the main body of the Union infantry. The following day the rest of Sherman’s division (including Grandpa’s unit) moved forward to the new position that offered a good position to gaze into Corinth itself.

(By May 25, the Union Army was entrenched on high ground within a few thousand yards of the Confederate fortifications. From there, Union guns shelled defensive earthworks, supply bases and the railroad facilities in Corinth).

By the end of the month, the Federals had engaged the rebels at Surratt’s Hill and Bridge Creek and were preparing to lay siege to Corinth. At a council of war, the consensus of Rebel thought was that being trapped in a bag was not the optimal course of action. General Beauregard came up with a ruse to cover the strategic withdrawal, using clever tradecraft to feed the Federals with bad intelligence. He ordered three day’s rations be provided to some of his men, who were in turn ordered to prepare for an attack against the Union forces.

(General P.G.T. Beauregard).

Beauregard was counting on the fact that some of those men would prefer not to participate in a foolhardy assault against superior forces. He was right. One or two men defected to the Union side with the information that the Rebels were coming for them. Artillery began to boom as the two armies juggled for position. Instead, the Confederates conducted a strategic deception. On the night of the 27th, artillery and tons of supplies along with the wounded and sick men were loaded on cars of the Mobile & Ohio Railroad and evacuated.

When a train arrived, the troops were directed to cheer as though they were receiving reinforcements and rations. Dummy guns- tree trunks painted black, and known as “Quaker Guns”- were set up on the defensive earthworks and campfires were lit in numbers that suggested a growing force, as buglers sounded regimental calls and drummers beat the cadence.

The main body of the Confederate force slipped away undetected, melting into the night, heading for Tupelo, MS.

When the first Union patrols entered Corinth on the morning of May 30, they found the Confederate troops gone with the morning dew. The Union force dug in for an extended fifteen-month stay.

The 72nd OVI did not stick around to garrison Corinth. They were directed to march to Memphis, TN, via La-Grange (53 miles), Grand Junction (7 miles), and Holly Springs (280 miles), starting the trek on the first of June, and arriving at Memphis (316 miles) on July 21st. That is 656 miles on foot, or an average of nearly 13 miles a day, rain or shine.

Then, the boys were directed to “other duties as assigned” in the Bluff City until November, 1862. At least they got a chance to take their boots off.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

Grant’s Goat

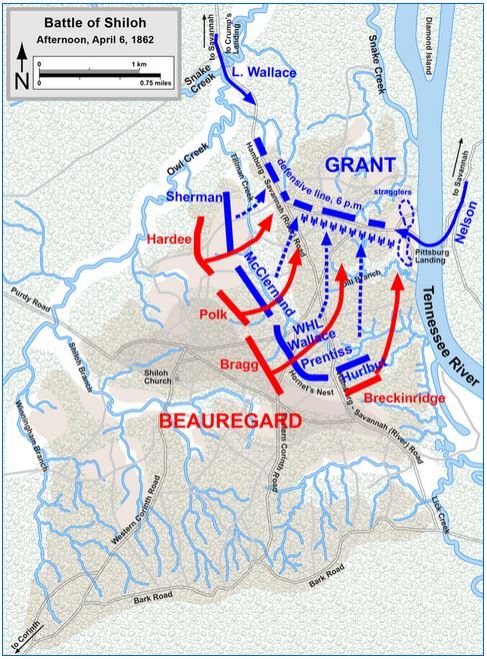

It is all about choice, you know? General Lew Wallace had a choice about the road he took to get to the Pittsburg Landing battle at Shiloh. I showed you a picture of the bend in the Shunpike- the spur to the left would have taken Lew Wallace’s Division to the River Road, and thence south to Pittsburg Landing. The Shunpike offered a direct and less muddy route to the Union right flank, defended by Tecumseh Sherman.

When it comes to Civil War history—or any history for that matter—there is often a vast difference between what actually happened and what people believe happened. There are people who care deeply about all this, and invest enormous emotional capital on what might have been the intentions of the men on the field. So, here is the situation on that muggy morning.

It is nine o’clock. Grant has arrived at the landing to confront a scene of chaos as Albert Sidney Johnson has attacked with decisive force- 50,000 confederate troops. For Grant, the situation has the hallmarks of an impending disaster. He decides to visit each of his commanders in the field, a trip along the lines that took him to Sherman’s headquarters on the extreme right of his line. He told an aide to get word to Lew Wallace that his presence on the field was necessary. Someone wrote it down, and a courier was dispatched to Crumps Landing. When Grant arrived on the ragged right wing, he told Sherman that Lew Wallace was on his way.

The copy of the order did not survive the battle, and the controversy began. Was Wallace directed to take a route, or did he have commander’s discretion in executing the order that Grant never saw written down.

Lew Wallace was a careful man, and apparently a caring one. Before advancing to meet Sherman at the Hamburg-Purdy Road, Wallace allowed his men a light lunch to prepare for the five-mile march down the Shunpike and Purdy Road. Only one major barrier to cross-country movement would hinder the progress of his Division: the Snake Creek.

Before completing the crossing of Snake Creek, staff Captain Rowley reached Wallace with the news that the right flank of Grant’s army was now disorganized and had been pushed back closer to Pittsburg Landing. The Federals no longer controlled the Purdy Road Bridge over Owl Creek, nor the position where the road approached the field of conflict.

Now consider that this was Wallace’s first Division-level Command, and that he was not a professional soldier. In other circumstances citizen-soldiers have ordered arcane maneuvers that worked out pretty well.

I am thinking of Joshua Chamberlain and the 20th Maine at Gettysburg. His position was the extreme left of the Union Line. Knowing that his men were out of ammunition, and judging that another charge by John Bell Hood’s Alabamans would prevail, he ordered an unusual maneuver: he ordered his left flank to advance with fixed bayonets in a “right-wheel forward” maneuver. As soon as they were in line with the rest of the regiment, the remainder of the regiment charged. The simultaneous frontal assault and flanking maneuver befuddled the 15th Alabama, which was broken.

Upon hearing that he could not proceed directly, Wallace decided on a “countermarch” maneuver. sending the lead brigade back through his column. This complex and rarely drilled evolution meant that his forward brigade would have to march through itself (think of a college marching band at half-time) and two other brigades stretched across three miles of road. He could, of course, have just turned the division around, but that would have resulted in a sequence in which the units he intended to keep in reserve would arrive in combat first, rather than last.

In the meantime, Sherman had fallen back to a position near the Hamburg-Savannah Road, determined to hold a bridge over Snake Creek, which he predicted to be Wallace’s fall-back line of advance.

I don’t know what the teamsters of the 72 OVI thought about the unusual maneuver, as the vanguard of the force reversed course and filed back through the line of advance. assumed would be Wallace’s second option. Wallace got his vanguard back to the River Road and moving down to Pittsburg Landing by 1430 as the fighting raged. Grant needed every man to stave off the Confederate on his center, a fury of combat along a sunken road that became known as the Hornet’s Nest.

Grant was agitated, and dispatched two staff officers to find Wallace’s Division, since the 5,800 soldiers might provide the winning margin. Lieutenant Colonel James McPherson and Captain John Rawlins followed a circuitous route to Overshot Mill on the Shunpike where they encountered the rear elements of the formation proceeding to the River Road.

Finding Lew Wallace further down the column, McPherson informed him the situation at Shiloh was dire, and urged him to hurry to support Grant. In curious decision, based on what he had been told, Wallace then told his lead men to take a break until the rear of the column closed up.

This delayed the advance for more than an hour, and he did not reach the battlefield until shortly after 1830 when the day’s fighting had died down. Wallace’s men had marched about 14 miles in nearly seven hours over roads that had been left in terrible condition by recent rainstorms and churned by previous Union marches. Wallace directed them to take up positions on the Union right, as Grant had directed that morning.

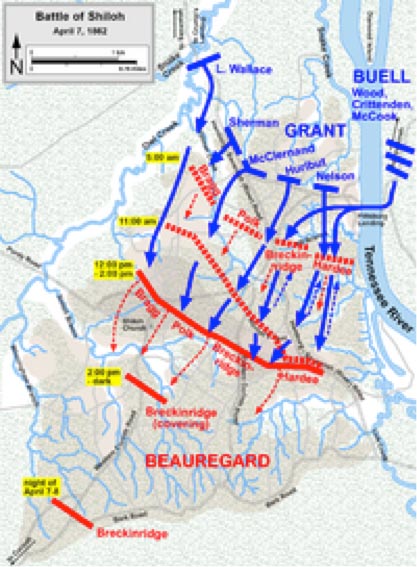

(Map of the Battle of Shiloh, Day Two, April 7, 1862).

The next day, April 7, two of Wallace’s batteries, augmented with another from the 1st Illinois Light Artillery were the first to attack, just at first light. Sherman and Wallace troops helped force the Confederates to fall back, and by 1500 that afternoon, the Confederates were retreating southwest, toward Corinth.

I think the real culprit in the whole affair was probably miscommunication, but it was clearly an example of spin. It’s possible that Grant’s orders, as written, directed Wallace to come in by the River Road, and Wallace, for whatever reason, elected to ignore that part, and take the Shunpike instead. It’s possible that this happened, and I’ve seen it speculated. But we can never really know. But I think it’s just as likely, if not more so, that Wallace simply made an honest mistake.

The Union won the battle, and Grant, as well as his men, had fought hard and well. But Grant did, of course, come in for what may very well have been the most severe criticism he faced during the entire war. The issue was connected to the sheer magnitude of what happened at Shiloh. The two-day battle produced more than 23,000 casualties and was the bloodiest and bloodiest encounter of the war to date.

Actually, it was much more than that. The number of killed and wounded from simply dwarfed everything that had ever come before, in all of American history. Nothing else was even close. People in the North were stunned by the casualty figures.

Keeping in mind here that we’re talking the spring of 1862, before the war had evolved into the bloodbath we now think of, the numbers from Shiloh were almost beyond comprehension. Combine those two things – a staggering number of dead and wounded, and reports in the papers that Grant allowed his army to be caught totally off-guard. It wasn’t true, or at least not completely- but we are aware of how this works in the public mind, and the search for the guilty began.

Someone had to pay for the negligence that led to all that butchery. And that someone was going to be Grant, unless another scapegoat could be found. As it turned out, Lew Wallace was just the man for that. It took years for Grant to relent in his assessment, and Wallace was relieved of command. He did not get another significant field assignment until 1864, when he may have saved the Capital from the depredations of Jubal Early in the battle at Monocacy Creek.

If Wallace had not delayed the Rebels, they might very well have penetrated the District from the north, with the goal of burning the city and perhaps capturing President Lincoln.

Despite that remarkable success, and the many positions of authority he occupied after the war, the “Slanders of Shiloh” were always with Lew Wallace.

My Great Great Grandfather, to the best of my knowledge, had no responsibility for the tardy appearance of his unit on the field. He would have been too junior a soldier to have made an effective goat. Besides, the 72nd OVI had business to conduct at Corinth.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

Stoney Lonesome

Major General Lew Wallace, his division, and my Great-great Grandfather stopped at Crump’s Landing to destroy the tracks of the Mobile and Ohio Railroad. It was one of the things armies did in those days, and I am interested to discover that my ancestors specialized (in appropriate context) the mass destruction of railroad rolling stock and tracks.

It sort of makes you swell with pride, you know?

Anyway, the 72nd OVI was with Major General Wallace because that is what the table of organization said: Fourth Brigade of the First Division of the Tennessee Army under William Tecumseh Sherman. They had marched out from Camp Chase, Ohio, in January and then on to Paducah, KY. From Paducah they were told to advance to Savannah, Tenn., in the first week of March.

It is 155 miles to go the distance- on foot. I won’t bother you with the mileage on every movement, but you get the drift. Consider for a moment that you are wearing a Federal-issue heavy wool jacket and trousers. The nature of the War in the West means you are carrying what you need, and in addition to rifle and ammunition, there is hard tack and bacon and beans to be carried.

Think of the humidity in the places they were marching, hay-foot, straw-foot, mile after mile. From Savannah, they marched 20 miles to participate in The Expedition to Yellow Creek, Miss., and then the occupation of Pittsburg Landing, TN, 15 miles to the north the next week.

That was the reason they were in Crump’s Landing on the 4th of April- to commit some vandalism of the South’s railroad lines.

These stories are not intended to be a version of the ‘Great Man’ theory of history. I despise revisionist historian Howard Zinn, by the way, and am only trying to get to the experience of a young Irish teamster through the lives of the notables. Grandfather left no personal record of his experience in the great Civil War, but these were the events that swept him along.

I must say, trying to get to him, I keep bumping into men who either seized greatness, or had ignominy thrust upon them. There had never quite been anything quite like what was happening in North America in 1862- and with luck, we will never see anything like it again.

Lew Wallace is one of those amazing fellows, a truly remarkable man, and more than the sum of his parts. He was a known attorney, son of an Indiana Governor, Union General, Governor of the New Mexico Territory, politician, diplomat and novelist, whose most famous work was the historical adventure story “Ben-Hur: A tale of the Christ.”

Some have called the 1880 best-seller the “the most influential Christian book of the nineteenth century.” I don’t know about that- there has been a lot of water over the dam since that century ended. I have put it on the list for reading some time in the future, but I did see the movie with Charlton Heston as Judah Ben-Hur, and that is going to have to be good enough for the purposes of why Wallace was at Crump’s Landing, an otherwise undistinguished landing on the verdant shores of the Tennessee River.

Wallace was not a West Point man, like so many of the figures who loom large in this chapter of our common history. Or uncommon, as it may be.

Lew’s father had attended the Academy, though, and he was favorably disposed to uniformed service. When the Mexican War came along in 1848, he volunteered, returning to civilian life when it was done.

He established a legal practice back in Indiana, and when the war clouds loomed he accepted an appointment as Indiana’s adjutant general and command of the 11th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment. He was at Fort Donelson, where Uncle Patrick was captured the first time, and his performance there earned him a promotion to major general. At the ripe old age of 34, he was the youngest MG in the Union Army.

If you want to look at great favor generating hubris, I suppose you can make the case. But what was going to happen at Pittsburg Landing was going to swamp anything that had happened on this continent before, and scapegoats would be necessary.

Lew’s force was left to conduct his anti-infrastructure task by Grant, who ordered the Army of the Tennessee (still known then as the Army of West Tennessee) to move to Pittsburg Landing four miles upstream.

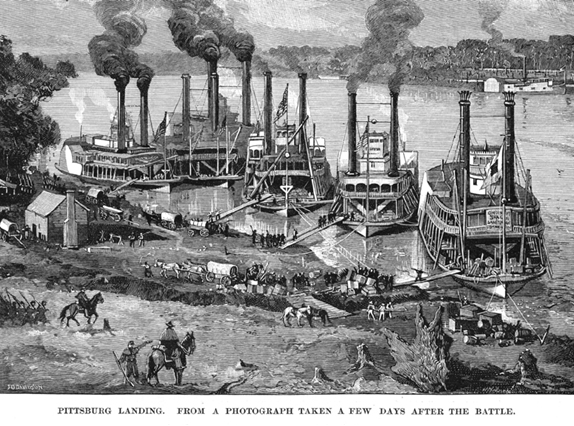

As a retired sailor, I find it of interest that this was an amphibious campaign, with command moving by steamship along the River. Lew Wallace had a boat- the John T. Roe. Grant had one as well- the Tigress- and this is the image of the Union Headquarters ships at the landing a few days after the biggest battle that had ever occurred in the Americas.

They got better at the art of slaughter, but this event was electric in the press descriptions of the scope and savagery involved.

But let’s go back to why scapegoats would be needed, and what Lew Wallace did to become one. On independent duty, Wallace had his cavalry destroy railroad tracks unopposed, but ran into resistance on the stagecoach road between Crumps and the hamlet of Adamsville.

Wallace decided to bivouac two brigades along the road between Crumps and Adamsville, and kept a brigade near his command vessel in the river. His Third Division engaged Rebels in several skirmishes, and for defensive purposes, directed his troops to began improving the road known as the Shunpike. The pike headed south from Stoney Lonesome, a picturesque name for small group of cabins on the stage road. The Shunpike ended at the Hamburg-Purdy Road, to the west of William Tecumseh Sherman’s Headquarters.

Opposing Grant was Albert Sidney Johnson with a force of nearly 50,000 Rebel troops. When he arrived at Corinth, MS, in late March, he ordered Major General Benjamin Franklin “Frank” Cheatham to advance to Bethel Station to prevent further Union raids.

Utilizing the ISR assets of his day- cavalry, mostly, along with snitches, spies and captives- he discerned that Wallace was detached from Grant’s main body. Grant was also waiting for the arrival When he arrived, Cheatham informed Johnston that he was facing Lew Wallace’s division and that it appeared to be detached from Grant’s main force. Johnston knew the Union plan was for General Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio to arrive and combine with the Army of the Tennessee to create an overwhelming force that would drive all before it.

Accordingly, Johnson decided to preempt and attack before the Union armies joined. Johnson was his own intelligence officer, and estimated that with Wallace detached, Grant had only 37,000 troops and he had the edge. Fortune favors the bold, I am told, and though he would not survive the fight he was about to start, Johnson was a bold son of a gun.

At dawn on April 6, 1862 almost 50,000 Confederates hit Sherman and Benjamin Prentiss at Shiloh, driving them back towards Pittsburg Landing. Wallace was awakened in his cabin on the command ship about 6:00am by an orderly. The sound of guns was apparent, and not far away. My grandfather’s horses would have become alert at the sounds, their ears twitching in alarm at what they would be asked to do.

Lew Wallace chose to concentrate his forces at Stoney Lonesome rather than Crump’s Landing because of the improvement his men had made to the Shunpike. Taking it south would be much easier than traveling the alternate route on the River Road, which had suffered heavily from recent heavy rains and the tread of thousands of feet and hooves.

Travelling south from Savannah, Tennessee, in his command ship, Grant met Wallace in the mid-channel of the Tennessee River. He directed Wallace to be ready to move out on command, but to stand firm for the moment. The Confederates had no presence on the river, and Wallace left the landing at Crumps with only a few sentries. Since the Union line of communication was on the water, he left a horse so that a courier could reach him at Stoney Lonesome if orders from Grant arrived.

Grant continued upstream to Pittsburg Landing, arriving about 0900. It didn’t take rocket science to know his forces were outgunned, and he issued orders for Wallace to move out and reinforce Sherman on the Union right. An aide scrawled the orders and dispatched a courier by boat to Crump’s Landing. From Crump’s, the courier rode to Stoney Lonesome and gave the order to Wallace, probably about 11:30 am.

And what Wallace did then colored the rest of his life, literary fame notwithstanding. He took Grandfather and the horses along with him, and therein lies the tale

(The site of Stoney Lonesome today. Wallace ordered his troops to take the curve to the right. The turn to the left would have taken him to the River Road. Ah, the road not taken…..)

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

twitter: @jayare303

War (And Love)

(Union troops at ease, reading letters and smoking in the field. Image USG).

James Foley was as excitable an Irishman as you can imagine- which is to say, he was a sort of passive-aggressive approach to events that were far larger than any individual, and a determined insistence on doing things his way.

He had emigrated from the green rolling hills of County Galway in the late 1840s, and followed the rails west as they opened the vast and fertile Ohio Territory. Admitted to the Union in 1803, Ohio symbolized the connection of the original colonies spilling over the mountains to the west, and connecting to the vast riverine network that drove expansion to the south to the Gulf and north into the Dakotas.

I was perhaps a little unkind to grandfather’s memory when I noted his decision to absent himself from the 72nd. A combat vet and shipmate wrote me to not be so judgmental. My pal understands a little about the nature of war and love- and he said it this way:

“If I may, don’t be to hard on Grandfather James, and this is from someone who’s been there. I met my bride in Hawaii for R&R in March 1970. I flew in with my pilot from Duc Hoa. He was meeting his wife, too, and we four did all the things associated with I&I. On the last morning, I left a tearful wife at Fort DeRussy to get the plane back to VN, it was the hardest thing I have ever done. I was scared but the futility of what we were doing is what nagged at me. I can only imagine what it must have been like in 1864 for a newly married immigrant; he did his part.”

I had to agree, and I am not sure that I would not have done the same thing that my GG Grandfather did. The other thing I noted after walking the field at Raymond, MS, was to realize what was expected of infantry in the days before vehicles. They literally walked all over the upper and lower South in that lesser known part of the Civil War.

Since James did not write to us here in his future, not knowing that his present would be of interest as our past, I have to look at his service through the lens of his unit. They kept impeccable records.

With the onset of the War, the 72nd Ohio Infantry was organized in Freemont, Ohio, in October1861. The process lasted through February 1862, with private soldiers mustered in for three years service under the command of Colonel Ralph Pomeroy Buckland. The Colonel had something in common with Patrick Griffin’s God’s Own Gentleman, Lt. Col. Randall McGavock, who had been mayor of Nashville.

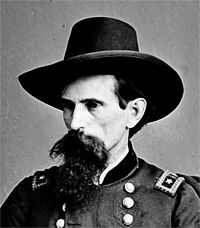

(Colonel Ralph Pomeroy Buckland, as a brevet Major General and Member of Congress. Image Library of Congress).

Buckland was mayor of Freemont, 1843 to 1845, and was a delegate to the Whig National Convention in 1848. He set his sights on state politics and served as a member of the Ohio Senate between 1855 and ’59.

Buckland entered the Union Army as Colonel of the 72nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry on January 10, 1862. Buckland also commanded the Fourth Brigade of the First Division of the Tennessee Army under William Tecumseh Sherman in the 5th Division of the Army of the Tennessee for the battle of Shiloh. For his sustained performance, he was promoted to the rank of brigadier general of Volunteers on November 29, 1862. During the spring and early summer of 1863, Buckland commanded a brigade in Sherman’s XV Corps in the siege of Vicksburg.

Like great-great grandfather, he tired of the war. Buckland resigned from the army January 6, 1865, and returned to Ohio after winning a seat in the US Congress. In the omnibus promotions following the surrender of the Confederate armies, he was given a brevetted promotion to Major General, with a date of rank of March 13, 1865.

So, that was Colonel Buckland’s war in brief. I have nothing like that for grandfather, except that he was a teamster and hence, a logistics specialist with a rifle. That has been a tradition in the family that went down through James’ son Pop to my actual grandfather Mike, who drove trains for the AEF in France in 1918.

But let’s stay focused. The canvas of the war in the West is a vast one, and follows the rivers and the rails: the 72nd OVI was attached to District of Paducah, Kentucky, to March 1862. Here is where they marched in the heat of the Southland:

1862:

Moved to Camp Chase, Ohio, January 24, then to Paducah, Ky.

Moved from Paducah, Ky., to Savannah, Tenn., March 6–10, 1862.

Expedition from Savannah to Yellow Creek, Miss., and occupation of Pittsburg Landing, Tenn., March 14–17.

Crump’s Landing April 4.

Battle of Shiloh April 6–7.

Advance on and siege of Corinth, Miss., April 29-May 30.

Russell House, near Corinth, May 17.

March to Memphis, Tenn., via La-Grange, Grand Junction, and Holly Springs June 1-July 21.

Duty at Memphis, Tenn., until November.

Grant’s Central Mississippi Campaign, operations on the Mississippi Central Railroad, November 2, 1862 to January 12, 1863.

1863:

Duty at White’s Station until March 13. Ordered to Memphis, Tenn., then to Young’s Point, La.

Operations against Vicksburg, Miss., April 2-July 4. Moved to join army in rear of Vicksburg, Miss., May 2–14.

Mississippi Springs May 13.

Jackson, Miss., May 14.

Siege of Vicksburg May 18-July 4.

Assaults on Vicksburg May 19 and 22.

Expedition to Mechanicsburg May 26-June 4.

Advance on Jackson, Miss., July 5–10.

Siege of Jackson July 10–17.

Brandon Station July 19.

Camp at Big Black until November.

Expedition to Canton October 13–20.

Bogue Chitto Creek October 17.

Ordered to Memphis, Tenn., and guard Memphis & Charleston Railroad at Germantown until January 1864.

1864:

Expedition to Wyatt’s, Miss., February 6–18.

Coldwater Ferry February 8.

Near Senatobia February 8–9.

Wyatt’s, Miss., February.

Operations against Nathan Bedford Forrest in western Tennessee and Kentucky March 16-April 14.

Defense of Paducah, Ky., April 14.

Sturgis’ Expedition to Ripley, Miss., April 30-May 2.

Sturgis’ Expedition to Guntown, Miss., June 1–13.

Brice’s Cross Roads, near Guntown, June 10.

Salem June 11.

Smith’s Expedition to Tupelo, Miss., July 5–21.

Camargo’s Cross Roads, Harrisburg, July 13.

Harrisburg, near Tupelo, July 14–15.

Old Town or Tishamingo Creek July 15.

Smith’s Expedition to Oxford, Miss., August 1–30.

Abbeville August 23.

Moved to Duvall’s Bluff, Ark., September 1.

March through Arkansas and Missouri in pursuit of General Sterling Price September 17-November 16.

Moved to Nashville, Tenn., November 21-December 1. James would have been required to re-enlist after his initial three-year obligation expired in October, which came with half his $800 dollar bonus and thirty days furlough. Since his future wife Honora, sister of Patrick Griffin, lived in Nashville, I suspect this is when he made his decision to stay home and see the elephant no more.

The 72nd went on without him:

Reconnaissance from Nashville December 6.

Battle of Nashville December 15–16.

Pursuit of Hood to the Tennessee River December 17–28.

1865:

At Eastport, Miss., until February 1865.

Moved to New Orleans, La., February 9–22.

Campaign against Mobile, Ala., and its defenses March 17-April 12.

Siege of Spanish Fort and Fort Blakely March 26-April 8.

Assault and capture of Fort Blakely April 9.

Occupation of Mobile April 12.

March to Montgomery April 13–25, and duty there until May 10.

Moved to Meridian, Miss., and duty there until September.

The 72nd Ohio Infantry mustered out of service at Vicksburg, Miss., on September 11, 1865. The war was over, and the Reconstruction began.

We will take that as the framework on which to hang the story of a bluff young Irishman in the biggest fight of his generation. We will see where it goes. On the upside, James was a teamster, and someone had to ride in the wagon, you know? How else would the horses know where to go?

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303