The 72nd OVI

Hah! You thought we were done with this? No way.

Great-Great Uncle Patrick had the gift of gab, and that is why he is the certerpiece of so many family stories about the sprawling history of the Civil War. is stories about his role as a teenager and young man in the War Between the States has been an entertaining thing to follow. He left a literary record that is a lot like talking to the grand old man, who invented his own commission and uniform to wear in the days when the Lost Cause still stirred the blood of Southerners, and the horror of the War had faded into a sepia-toned memory of the might-have been.

I thought walking the field at Raymond with a copy of Patrick’s account of the fall of his Colonel, Randall McGavock, would slake the mental thirst for some closure on that long-ago event. Instead, it opened up something entirely new: the possibility that my Mom’s line of Ohio Irish were on the same field and in the same fight.

Let’s meet Great Grandfather, whose persona is not nearly so dramatic as that of Uncle Patrick, but whose sweat and blood was shed with Company K, 72nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. He wore the Blue for three years, part of an ethnic Irish contingent of immigrants who cheerfully fought for both sides in the War for the West.

After the Griffins settled in Nashville, Patrick’s sister, Barbara Griffin, immigrated to America. In 1864, she caught the eye of Irishman James Foley, who was regimental teamster in the 72nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. He was described in his enlistment documents as ‘”ruddy complexioned, six foot tall, blonde-haired” Irishman.

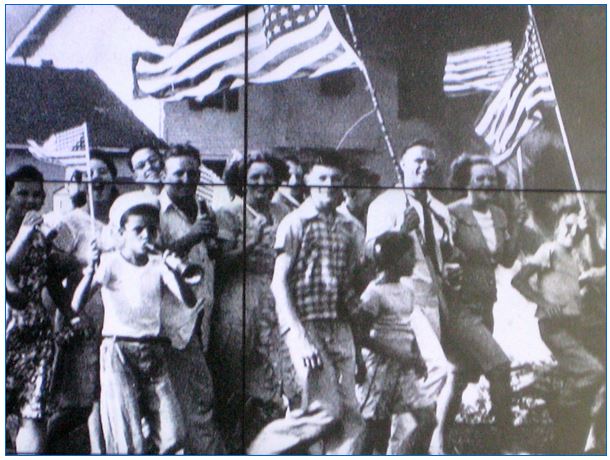

If there is an image of what he might have looked like, it might be that of his grandson, my grandfather, Mike. This image is from 1916 in Bellaire, OH:

In the course of his war in the West, James survived the epic battle at Shiloh and the brutal siege of Vicksburg, but Barbara proved irresistible and much more successful than Pemberton’s defense of the beleaguered river city. But more about that story in a moment.

In terms of the connection, we have relied on uncle Patrick’s remarks to his veteran’s group in 1905. On Mom’s side of the family, the Union side, she remembers Pop as an old man in the late 1920s. Pop was the son of civil war vet James, who lived in Dillonvale and Belleaire, OH, until his death.

I wish I had known more about how this all worked back when I could have done something easy, like ask her.

But all that said, there are some things that are easy enough to put in perspective, like the Regimental diary of the 72nd OVI.

I sat in the National Archives years ago and actually held his service record in my hands. I took extensive notes, which have migrated into some memory hole of another, and will have to look for them in the vast hoorah’ nest of files in the office in the garage down at the farm.

But the places I know James was located include these:

Crump’s Landing, TN

Shiloh, TN,

Siege of Corinth, MS,

Russell House, MS,

Jackson, MS, (two days after the battle at Raymond)

Siege of Vicksburg, MS,

Big Black River, MS,

Brandon, MS,

Hickahala Creek, MS,

Guntown, MS,

Harrisburg, MS,

Tupelo, Ms,

Old Town Creek, MS.

That takes the unit up to July of 1864, when the three-year enlistments were all expiring n masse, and the 72nd appears to have been pulled out of the line for rest, recreation and refitting. Most of the vets who had been with Company K were entitled to a re-enlistment bonus and thirty days home-leave. James took it, signing on Uncle Sugar’s contract and pocketing half the cash bonus and going home on leave.

Problem was that he didn’t come back, and the last card in his service record, after the fancy re-enlistment certificate, is the notation: Deserter.

There is more to it, of course, and he had his reasons. we will take a look at some of the venues of his service before voting with his feet. His departure from the war means I don’t have to research Little Harpeth, TN, Nashville, TN, the Pursuit of General John Bell Hood, and the last combat action at Spanish Fort, AL.

But I might anyway. And there is a love story in here, too, which we will get to in good time.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

While I Was Gone

(Mr. Claude Minnich, almost former owner of Clark’s Hardware on historic East Davis Street in downtown Culpeper. Photo courtesy Vincent Vala, Star-Exponent Staff Photographer).

OK- this is going to be a little disjointed, so forewarned is forearmed, you know?

The trip to New Orleans and Raymond, Mississippi put 2,335.6 miles on the odometer of the Panzer in a week and helped clear my head of the inside-the-Beltway static.

Here it was in a nutshell. There was a distressing amount of Spring roadwork on I-81 down where the dagger of Southwest Virginia spears the flanks of Tennessee and Kentucky. A lane was closed. Drivers of four and eighteen wheelers promptly got over as advised, when able, and for the last quarter mile there was a single lane of us courteously waiting to get through the construction zone. Not one person screamed up the empty lanes to the orange cones to barge in and cut off those motorists who had patiently waited.

When I approached the Capital on I-66, same deal, except the drivers in the lane that was closed increased speed to cut us all off. Everyone one up here is nuts, which I recognize includes me.

It was an amazing adventure in America, with nice people and amazing history. I visited the World War Two Museum near the French Quarter, talking to a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto on the 70th anniversary of VE Day, hanging on the Gulf Coast and later walking the battlefield in Northern Mississippi where Great Great Uncle Patrick Griffin had the experience that shaped his young life.

But there were things going on while I was listening to the satellite radio in a semi-hypnotic state as the new tires on the Panzer ate up the miles.

Attached is an experiment- as you know, I try to publish something daily- and that means sometimes the episodes get spread out across several days. In the case of the Raymond experience, it ran to five linked episodes. I cleaned them up a bit- don’t worry, many of your favorite typos have been lovingly preserved- and offer the collected set as the attached Portable Document File. Depending on what people think, I may start the process of collecting some of the more memorable past adventures in similar fashion so they are all contained in a single discrete and compact place.

We will see.

History continued to be made here. The redoubtable Alison Brophy Champion, longest-tenured local reporter for the Clarion-Bugle, wrote a dramatic article that appeared the morning after I got back to the farm from the road that got me quite agitated.

Well, I was agitated enough from the road, and one night’s rest at the farm wasn’t going to change that. But her story announced that today- the 16th of May- is it for Clark’s Hardware. When the doors close at 5:30 this afternoon, that’s it. The hundred -year tradition of having a quirky old store that has literally everything you could possibly want, maintained by people who know where everything is in the crazy assortment of merchandise, is done.

The Clarion-Bugle is a small town paper, and I know that Alison has to take an even hand with things, but Claude Minnich, the owner of Clark’s since 1980, is being pushed out by the organization that owns the building, the Masons.

Apparently they have plans to renovate the building and go upscale, in keeping with the gentrifying tone of the block that leads down to the Depot, and Claude and his store do not have a place in it. This is a huge bummer. That leaves the big-box Lowe’s the only alternative for stuff you need, and I suffer from Big Box disphoria. Every time I get inside the vastness of the superstore I forget why I came, or launch off on some project I have not thought through and then screw up.

When last I mentioned this sad business about Clarke’s to you, I visited the place to solve a deficiency at the farm: I needed a lid for my cast iron skillet, and when I first learned that a local institution was being tossed on the altar of progress, I hustled in. I am glad I did.

When Claude slapped a 30% sale price on everything, the Lodge cast iron collection was the first category of goods to go. When I got there Wednesday, the last piece of Lodge cast iron remaining was an 18-inch lid that fit nothing I own.

C’est la vie.

The last piece of Lodge is at the left. You can see the paint coming down from the pressed tin ceiling over a much-depleted inventory that used to run to 30,000 items. A copy of the going-out of business flier is at right. Things moved so quickly that the planned auction was called off.

In a separate story, Alison informed us that my favorite local winery is expanding. The Old House people do a great tasting and it is only about four miles from the farm as the crow flies. I have told you before about Belmont Farms, the distillery just to the south of Refuge Farm, and the marvelous moonshine and vodkas they produce in a real copper still.

Well, Alison broke the story that the winery is going to offer some competition. They are adding an Old House Distillery, a still that will produce brandy, vodka, agave and rum while providing distilling services for local wineries to create their own port-style wines.

The combined beverage-centric offerings on the 75-acre farm will make Old House one of the first winery-distilleries in Virginia.

So, with the loss of one institution we gain another. Life in the country.

And as to life in the city? It was good to be back at Willow in the evening again. Tracey O’Grady is adding some items to the menu for summer. I was talking to Old Jim at the apex of the bar last night, just like he was not about to flee to Las Vegas with Chanteuse Mary as soon as they can sell their condo. Former Willow sous chef Robert was just down the bar with his lovely girlfriend Kay.

Jasper and Sammie were working a pretty good crowd on the patio. Heather 2 was bustling around doing General Manager stuff, and Frankie the bar maid gave me the address to a place in Vienna, VA, that reportedly sells real Cornish pasties just like the ones back in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. JPeter was to my right with Gordon, the alternative energy consultant and Chairman of Lightsense Technology.

We talked enough to let me know that he knows the whole thing doesn’t make much sense, economically, and that a distributed network of thorium-fueled reactors is the way to reduce the use of fossil fuels. He knows where the money is, though, so he is playing along with where the money is. He used to be an EPA bureaucrat, so he knows. We should probably get around to doing something about it one of these decades.

Anyway, Tracey was experimenting with some ideas for next week, and very kindly brought out her latest creation for us to share: Irish Nachos.

It was an amazing creation of hand-cut thick deep-fried potato chips layered with Tillimook melted smoked cheddar cheese, chopped scallions and sour cream.

Robert summed up the reaction for the crowd, and as executive chef at the Tonic restaurant in Foggy Bottom, he is a recognized authority: “Damn,” he said. “Those are good.”

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

Raising the Dead

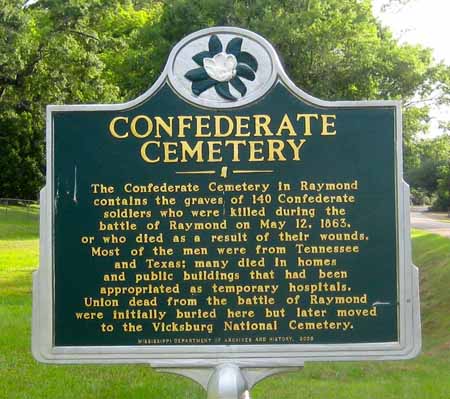

(Those who died during the Battle of Raymond were buried on a hillside in the Raymond Cemetery. The hillside later became the Raymond Confederate Cemetery. Randal McGavock was buried here the day after the battle of Raymond, but later removed. The plot is mowed neatly and well maintained. Photo Socotra).

I felt triumphant that our search had been successful, and what had been family myth was now filled in memory and digital record with a sense of space, and place. The air was moist and gentle on our skin and we turned back on the black-top and drove slowly down to Highway 18 for the right turn north back to Raymond. I took a sheaf of notes out of my back-pack and glanced quickly down Uncle Patrick’s account of the aftermath of the battle, recapping the events that happened after the battle.

“So, Patrick goes back to get Colonel McGavock’s body, which was just where he left it, near the edge of bluff near the sign we found. He got two members of H Company to volunteer to go with him and carry the body. Gregg’s Confederates were beating feet north to escape the Yankees.”

“The ladies of Raymond had made lemonade and a light lunch for them,” said my friend, negotiating off the big bypass road and back onto the human scale of Port Gibson Street. “They could not stop to tarry, and you can say that the Yankees ate their lunch.”

“Uncle Patrick and his comrades were making a slow go of it with the body. They were overcome by the vanguard of the Yankee advance, and Patrick had to threaten his friends at gunpoint to keep them from running. Seeing that capture was inevitable, he let them go. The Union troops gave him the raspberry, but he said he was beyond caring. Eventually the commander of the rear guard, a Captain of Infantry named McGuire, took pity on his fellow Irishman and had the Colonel’s corpse put in a wagon to be hauled to town.”

“Sounds a little like the movie Weekend at Bernies,” smiled my friend, swerving off the road onto the grass near the historical marker at the Raymond Cemetery. We dismounted and walked over to read what was on it.

“A hundred and forty Confederates,” I said. “Where did the Union dead go?”

My friend smiled, a little sadly. ”Look at the terrain, going up slope toward the wrought iron fence around the Confederate graves.” I did, and the lowering sun showed a pattern of shadows revealing oblong dimples under the verdant greensward.

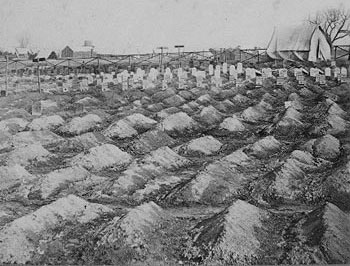

“They were all here, too. There was no provision for a Graves Registration Service in either of the Armies. After the fight, combat troops were detailed to bury the dead before they putrefied. There was no embalming for most of them. There wasn’t any specific provision for it, unless a Suttler following the Army was there to provide the service at private cost. The threat to public health was the biggest deal in what we know now as the first modern mass war.”

(This is what the cemetery at Raymond would have looked like in the days immediately after the battle. This image is of the graveyard at the City Point Hospital near Richmond, VA. Collection of the New York Historical Society, nhnycw/ad ad35012).

“No wonder most of the casualties were from infection or disease. But if the Union dead where here, where did they go?”

“Probably to the National Cemetery in Vicksburg. That is a story in itself. The number of soldiers who died between 1861 and 1865 is estimated to be north of 600,000.”

“Wait, that is more than all the other wars in American history until Vietnam!”

My pal nodded. “Yep, and they were buried where they fell. That lead to a bold plan devised by Army Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs to find, disinter and re-bury the Union dead in a new system of national cemeteries.”

“I knew he directed the first burials at Arlington, partly out of revenge for the death of his son in combat. But I had no idea he was behind an entire campaign to dig up all Union Corpses and bury them together.”

“Aside from the War itself, that was the first big government social program. As Reconstruction was rolled out, resentment was growing across the South. Union cemeteries in the southern towns were becoming an emotional issue. General Meigs dispatched teams to all the major battle sites in a six-year massive Federal program to locate, disinter and rebury the Union dead. Ultimately, well over 300,000 bodies were reinterred in 74 new national cemeteries. They tried their best to identify them, eventually naming more than half. Clara Barton ran her own agency to locate and identify the dead.”

“That boggles the mind, no kidding. Clara’s vision for the Red Cross came out of her experience in Fairfax County and the search for the missing after the war. I saw that her Missing Soldiers Office in DC has become a museum. I will put that on my District Bucket List. Was that only for the Union Dead?”

“Of course. The South was vanquished. Identifying and memorializing the Rebels was a local or State matter, and there was no money for that. Outraged at the official neglect of their dead, white southern civilians, mostly women, mobilized to accomplish what federal resources would not. That is where the cult of the Lost Cause began in the sense of violation. The ladies of Columbus, Mississippi began to decorate the Southern graves in 1866.”

We unlatched the wrought iron gate and walked slowly down the rows of Confederate graves. They are marked with distinctive stones that come to a gentle point, unlike the Union markers that are gently rounded. It is said they were carved that way so that Yankees wouldn’t sit on them.

“And the whole Memorial Day holiday flowed from that, right? But even that is controversial. Some people claim it was freedmen in Charleston who began decorating the graves of Union prisoners in 1865 to commemorate what the fight was really about.”

“Controversial indeed. In fact, like the social changes brought by World War II, there is one America before 1861, and completely different one after 1865. So, your Uncle Patrick brought the Colonel’s body back to Raymond, and then what happened?”

“Patrick was a prisoner, again. By nightfall he had been taken to a hotel in Raymond that was being used as a prison by the Union forces. The Colonel’s body spent the night on the porch. The next morning, Captain McGuire stopped at the Hotel to deliver a two-day parole. Free to move around, Patrick found a carpenter and paid him $20 to build a plain wooden coffin. He then hired a wagon, and a procession of prisoners under guard gave an escort of honor, and the burial was right here. He got the grave marked so the Colonel’s relatives could find it easily. Then he went back to being a POW.”

“He escaped later, right?”

“That is his story, and he stuck to it the rest of his life. His daring escape from a prison boat and the trip back down the river to re-join his family is quite an epic. Ultimately, he rejoined the fight as a headquarters scout and railway saboteur in the Georgia campaign of that crazy Texan John Bell Hood.”

“Good story,” said my friend.

“Might even been true. Patrick named his daughter Louisa McGavock Griffin after the Colonel.”

“What happened to the Colonel’s body after Raymond?”

“My understanding is that McGavock’s sister Ann and her husband, Judge Henry Dickenson, traveled to Raymond and made arrangements for the body to be brought to their home in Columbus, MS. After the war, the remains were moved one final time to Mt. Olivet Cemetery. On St. Patrick’s Day, 1866, Patrick’s Colonel finally came to his final destination and was interred in a formal Masonic ceremony. They say most of Nashville’s Irish population was there to honor their former Mayor. Far as I know, he has remained there since.”

“He moved more in death than a lot of people do in life. Care for a drink?”

I did indeed. We walked back down the hill and mounted up to drive the back roads back into the future, and presently we found ourselves in the bright lights of Clinton.

We stopped at an Applebees near the Holiday Inn Express. It was Mother’s Day, and the crowd was brisk and very diverse. We sat at the counter in the middle of the restaurant and the server brought us some menus.

“Sweet tea?” she asked pleasantly. “Sunday, no liquor.”

She must have assumed we were ignorant Yankees, but was courteous about it. It is the way of things down South.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

Where McGavock Fell

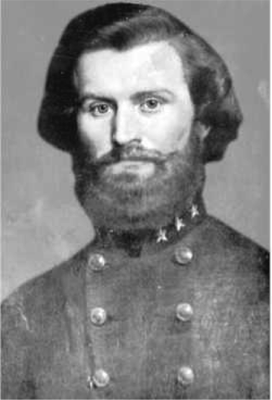

(Colonel Randall McGavock, 10th Tennessee Irish Regiment, CSA)

We walked back up the asphalt path that surrounds the core area of the battlefield at Raymond slowly. Both of us are having some mobility problems these days- I beat my knees into submission and the arthritis is painful, amplified by that damned ruptured quadriceps a couple years ago. My pal took a bad fall in an adventure on his mountain property a few years ago, and the rehabilitation has been long and not complete.

But we were both happy to be someplace where history had been made, and there were stories that were told about what had happened here. A local approached us, headed for the old disused concrete bridge over Fourteen Mile Creek.

“Howdy, all ya’ll,” he said as we passed, and we responded the same way.

“He probably knew we were Yankees,” my pal said.

“I have no doubt. But I had kin on the field, maybe on both sides. I wish I could remember what Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment Great Grandfather was in. I saw on the sign that the 20th Ohio was right here, in the center of the Union counter-attack.”

“Tantalizing thought, but you should be able to do the research when you get home.”

“I wish I had a copy of his service record. I held in in my hands years ago at the National Archives. I was pretty amazed that they were able to whistle it up in a half our. I wouldn’t think there would be that much call for the original records these days.”

We approached his white car in the parking area at the north end of the field. “I will show you the Texas Monument across the road. It is on private land, but the battle itself extended almost a mile in that direction, along the high ground.” He described and arc with his hand. “I trespassed the last time, but the gate was open and the owner showed me up to the signs that describe what happened up there. The Friends of Raymond had them placed there in the last few years.”

“So that is the ‘non-contiguous’ property they were talking about? Do we have to trespass to get there?”

“If the gate is open we can just ask the owner if it is OK. I am sure they will understand if you tell them the story.”

“So, I didn’t get it from Uncle Patrick’s account of the fight. I didn’t understand that the combine 10th/30th Tennessee Irish were the extreme left flank of the Confederate line.”

“Yes, the understrength 10th had been augmented with the 30th to bring up their TOE to something near combat effective. They got here on the 11th, marching from Port Hudson to Jackson, and then the twelve miles to Raymond.”

“They did a lot of marching. They must have been fit- and particularly in those woolen uniforms. I heard that Colonel Randall McGavock bought them for his men out of his own pocket- fine things. Patrick said the jackets and pants were Confederate Gray with a scarlet line running down the pant legs. The hats were gray with scarlet trim. The shirts and insides of the jackets were also scarlet. The officers got crimson and gold trimming on their jacket sleeves.”

“Not many got uniforms that fancy. General Gregg found this position to give fight, with the creek in front and the high-ground to his back. The 10th was up there,” he said pointing. We got in the car and drove back toward the modern route of Highway 18. Directly along what would have been the front lined there was a granite memorial to the right of a well-tended gravel drive with a gate that was firmly closed.

“We will have to try it from the other side,” said my pal. “I think I can find it.”

I said that I needed to get out and see the Texas monument.

“The Texans have been doing that lately for their Civil War battles. I guess it is because their economy is going pretty well.”

This one was relatively small- a little taller than me, and with a dense long inscription on the side facing the highway. The words read:

UPON THIS FIELD ON MAY 12, 1863, SOLDIERS

OF THE 7TH TEXAS INFANTRY, LED BY REGIMENTAL

COMMANDER COLONEL HIRAM B. GRANBURY, AND OTHER

REGIMENTS OF BRIGADIER GENERAL JOHN GREGG’S

BRIGADE FOUGHT WITH GRIM DETERMINATION AGAINST

TWO DIVISIONS OF FEDERAL FORCES UNDER COMMAND

OF MAJOR GENERAL JAMES B. MCPHERSON.

THE UNION ADVANCE WAS PART OF A LARGER

CAMPAIGN DESIGNED TO CAPTURE THE STRATEGIC PORT

CITY OF VICKSBURG ON THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER.

LEADING THE CONFEDERATE ASSAULT AGAINST THE

FEDERALS, GRANBURY’S TEXANS STEPPED FORWARD

AT NOON AND SURGED ACROSS FOURTEENMILE CREEK,

WHERE THEY MET THE ENEMY IN FORCE.

THEY VALIANTLY STRUGGLED WITH REGIMENTS

FROM OHIO AND ILLINOIS, WHILE ALL ALONG THE

BATTLE LINE THE SOUTHERN SOLDIERS OF GREGG’S

BRIGADE FACED THREE TIMES THEIR NUMBER.

DESPITE THEIR COURAGEOUS EFFORT, THE

CONFEDERATE TROOPS WERE CHECKED AND

FORCED FROM THE FIELD AROUND 4:30 P.M.

THE ENGAGEMENT AT RAYMOND WAS A PRECURSOR

TO THE INTENSE FIGHTING TO FOLLOW

DURING THE SIEGE OF VICKSBURG.

IN THE BATTLE OF RAYMOND, THE TEXANS LOST

22 MEN KILLED, 73 WOUNDED, AND 63 MISSING IN ACTION.

A MEMORIAL TO TEXANS WHO SERVED THE CONFEDERACY.

I had to take several pictures of the inscription to get it all in. I got back in the car and we backed up and got pointed toward the highway again.

“I am pretty sure I know how to find the plaques,” he said. “But it might be a long walk in the woods. We turned onto the highway and proceeded north to the first road that seemed to lead in the right direction and drove past some houses. We didn’t want to park in anyone’s driveway, but there was a derelict house almost completely overgrown with some fields behind, revealed by a tractor cut through the thick underbrush.

We pulled into the gravel of what had been the driveway, parked and dismounted. We walked toward the field, passing the overgrown house.

“How is it that something with a roof on it could become so worthless that they walked away?” I asked.

“Maybe it is just the farmland that has any value, or maybe it was part of the battlefield property that the Friends of Raymond bought. I don’t know.”

“Just so long as no one minds we are traipsing around their property,” I said. We walked on to the middle of the field. No markers visible. We didn’t know whether to go left or right at the tree-line, and decided that right was the best possibility. The next field was likewise barren of interpretive signage. I was starting to lose hope when my pal let out a whoop! “There it is! Come on!”

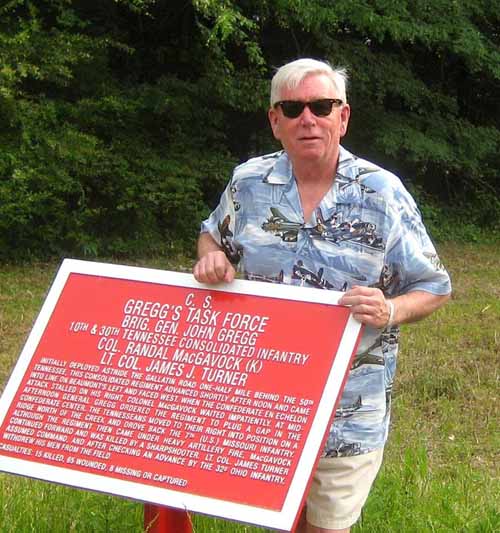

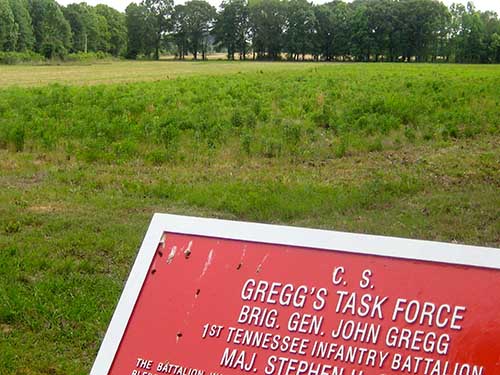

Actually, as we approached, we saw there were two of the red metal plaques set on sturdy poles and sunk in concrete.

“So this was the extreme left of the line?” I asked.

“It was until the 10th started to move in echelon back toward the creek where we were before. The plaques had additional information:

“At noon, Gregg charged with the 7th hitting the 20th Ohio and the 3rd hitting the 23 Ind. surprising and driving back the Yankees. At 1:00 p.m., the 50th and the 10th were ordered forward. Lt. Col. Beamount of the 50th then saw what Gregg had not yet seen. Two Yankee divisions were massing to attack in his front. He withdrew his regiment to the rear. This left a 400 yard gap in the line with the 10th all alone. By 1:30, the Confederate right began to collapse. McGavock’s vision was blocked by the woods and had no idea that the 50th was gone. When Gregg discovered that the 50th had disappeared, he ordered McGavock to stop the Yankees. With his sword in his hand, he turned toward his faithful Irishmen to signal to advance. With a deafening Irish-rebel yell, they surge into the oncoming Yankees. After making the signal to advance, McGavock turned to face the Yankees. At that moment, a single Yankee Minie ball struck him in the heart, knocking him to the ground, mortally wounded.”

(Patrick Griffin, in the day).

We read the words in silence. “This is where Uncle Patrick comes in, at least according to his version of the story. He said he was standing about two paces in the rear of the line and Colonel McGavock was standing about four paces behind him. They had been engaged for about twenty minutes when he heard a ball strike something. He realized it was his Colonel, wearing that red shirt of his under his gray frock coat. The Colonel was about to fall. He caught him and eased him down with his head in the shadow of a little bush. Patrick knew he was a goner, and asked if he had any message for his mother. The answer was: ‘Griffin, take care of me! Griffin, take care of me! He lived only for a few minutes. Must have been right here. Would you take a picture of me here?” I looked skyward…”Patrick!” I shouted. “It took a while, but I made it!”

We looked around the tree-line, seeing where Colonel McGavock would have led his wild Irishmen, if he had lived.

“So that was it or Patrick’s part of the war in the west. He continued to fight until the ‘Bloody Tinth’ withdrew from the field. Then he went to the Lt. Colonel who had risen to command with McGavock’s death, and told him he was going back to get McGavock’s body. He told him he had made the promise as the Colonel died and he was going to ensure he got a proper burial, whatever the consequences.”

We started the long trudge back to the car. My legs were feeling a little rubbery. “I am glad I am not carrying you on foot back to Raymond,” I said to my pal.

“And I am equally glad that I am not carrying you, my friend. Perhaps we should stop at the Confederate cemetery on the way back to town.”

“I assume that is where Randall McGavock was buried, the first time. At least that is where Patrick put him. The dead used to move around a lot more than they do these days. I looked around the green fields and the shadows from the trees that hugged the high ground.

In a strange way, I felt quite at home.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

Fourteen Mile Creek

We were walking the paved loop around the core battlefield at Raymond. It was a sunny Mississippi afternoon, the air languid and soft against our skin. There was another walker on foot, maybe a quarter mile ahead, and a jogger over by the abandoned concrete road and bridge across Fourteen Mile Creek.

“The Raymond battlefield had remained nearly unchanged for over a century,” said my friend. “Certainly in the time my father lived here. But the sprawl of development even came to sleepy country Mississippi in this new century. The improvement of Route 18- you can hear traffic from it beyond the trees- was resulting in commercial and residential development. That new activity vaulted this field up to one of the Top Ten endangered Civil War battlefields, according to the people at the Preservation Trust.”

“I have belonged to the Trust for a long time, and I am always good- or at least was- for a twenty spot to support good works.” I looked at the remains of what had been a bridge across a little tributary stream. “Do you think that was here in 1863?” I said, gesturing at the tangle of vines and fallen beams.

“I don’t know. This is probably the path of the old farm road,” he said, pointing down the narrow paved lane that ran straight as a die toward the end of the property.

“I donated specifically to the Raymond fund-raising campaign, and a fairly significant check to help purchase the high-ground at Brandy Station, where that jerk built the McMansion Spite House on the site of J.E.B. Stuart’s headquarters,” I said. “It does my heart good to see the crest of that hill naked again when I drive by.”

“Me too. It was in 1998 that plans were announced to pave over the pastures and put a strip mall fronting the highway. The people of Raymond got alarmed at the idea, and a group of concerned citizens formed the Friends of Raymond. They raised enough money to purchase forty acres that was going to be developed, and started buying other chunks of property along the battle lines.”

I looked to the left, at the peaceful green pasture that had been the line of advance toward Fourteen Mile Creek, and tried to imagine what it would have been like with a Seven Eleven, a gas station and a Dollar Store on it.

“So, they just about doubled the size, to include the area where your Uncle fought. We will go over there later, and I think I can find it. They put up a marker, but I had to trespass to get to it last time. We will have to approach from the south.”

We walked along and I began to sweat. “I am glad we are not here for the actual anniversary,” I said. “I bet on Tuesday there is going to be a big deal. I prefer to contrast the tranquility of the present with the idea of the chaos of the past.”

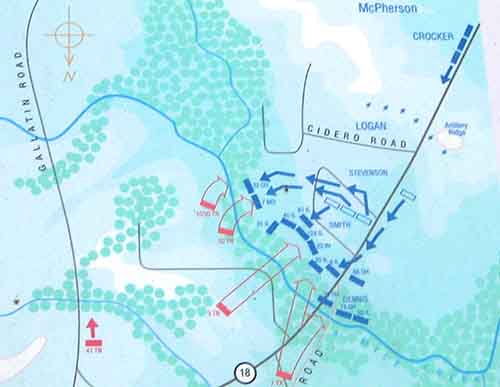

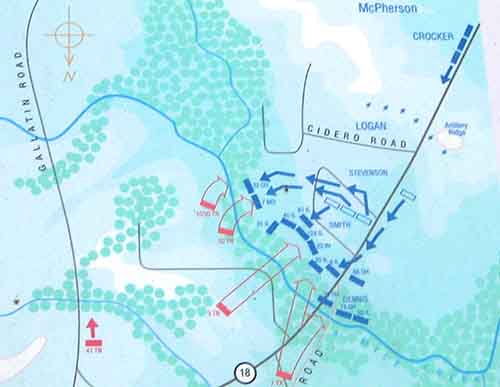

“The terrain hasn’t changed, of course, but the roads and trees have. I think this path was the road the Union troops came up to confront General Brig. Gen. John Gregg’s force. You can see there is a part that goes beyond the park boundary, and the remains of another bridge. The concrete road over there replaced it, I think, and ultimately the new Highway 18 was constructed off beyond the trees. The battle lines ran from off the Battlefield property to our right across the two newer roads. And the trees around us were not here, since we can’t see the Confederate cannon behind us on the bluff.”

“It is hard to figure out what you are looking at without seeing an old-time map superimposed on the modern features.”

My friend nodded as we came to a sign telling us not to go any further down the lane that crossed the stream. Another ancient wooden structure had fallen into the stream, and the asphalt walking path turned sharply to the left, paralleling the creek.

My friend went beyond the sign and told me to come with him. We stood and looked down the steep banks of the watercourse. “This is the major feature of the field. It was a natural trench. Gregg’s men had to cross it, charging the Yankees when they thought they had the advantage on them. The other units were arrayed on the high ground across the modern roads.”

“This is a great natural fortification,” I said looking at the tree sheltered streambed. The steep sides were at least ten feet above the foot or so of water flowing languidly through the rocks and fallen limbs. “But to advance across it and then have to fall back. Jesus.”

“Yeah. Gregg thought he was facing a much smaller force when he launched his attack at the Union front. He thought he was going to roll up a Union brigade. Instead, he was assaulting the front of an entire Union Army Corps. There were 12,000 Federals pouring up the road against his 4,000.”

We walked the quarter mile up to the 1920s-era Paper Moon-style bridge. On the other side of the creek were two cannon, placed to note the flying advance of the Michigan artillery. On the high ground of the field to the south were arrayed the snouts of twenty Union cannon.

“God, this was a killing field.”

My friend nodded. “Yes it was. Look at Fourteen Mile Creek from here,” and pointed to the deep chasm that provide natural protection for the Union advance as the Confederates were hurled back toward Raymond.

“Heavy fighting broke out along the slopes and low ground as the two forces collided in clouds of smoke and dust. It was a fog of war,” my friend said thoughtfully. “And I mean that literally. The stalemate here at the creek was finally broken when General McPherson massed his artillery and began delivering barrage on Gregg’s men. These Michigan guns were probably firing grape shot, mowing down the Rebels.”

“Not a pretty sight, I imagine. What made them stand and not run?”

“Well, they did, eventually, but heavy battle smoke and difficult ground prevented Gregg from knowing he was facing a buzz saw. The Texans to our right and the Tennessee Irish were moving in echelon toward the center, where the bulk of the fighting was happening.”

More than 500 Confederate soldiers were killed, wounded or missing on the field. Slightly less for the Union. Still, it was a sharp encounter. And the vigor of Gregg’s attack convinced U.S. Grant that he could not drive from here to Vicksburg and leave the Confederates in Jackson at his back. This fight changed the course of the campaign. Grant went against Jackson, and that forced the battle at Champion Hill, a much larger engagement than this was.”

“Good to know. This fight was it for Uncle Patrick. He got captured again as a result of some heroics. His unit was on the high ground off across Highway 18, right?”

“Yes. I think I can find it. We may have to trespass. You up for it?” We started the walk back around the field to the car. The air was humid, but not oppressively hot. The field was peaceful, and we were alone on the field.

“Hell, yes,” I said. “I just hope no one shoots us. That would be too ironic.”

My friend just smiled.

Tomorrow: Where McGavock Fell

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

The Field at Raymond

There is nothing like walking a battlefield to understand what happened on it. The terrain is all, an imperative you can only feel with your own legs, and marvel at what was expected of the legs of ill-fed people in heavy woolen uniforms on a humid Mississippi day. And add the realization and the simple fact that a watercourse can provide an opportune trench of opportunity, and overwhelming force, can impose the will on the unwilling.

My dual purpose for being in Raymond, Mississippi, was to see my pal (I mean, how often do we find ourselves I Mississippi at the same time?) and to find where Great Great Uncle Patrick had performed the acts that gave him the Civil War equivalent of his fifteen minutes of fame, and try to understand it. We were there in Raymond, almost on the actual anniversary.

We turned south under the shadow of the water tower and headed south, the diametric opposite of the direction from which U.S. Grant and two Corps of Union troops came. Confederate General Gregg and his forces had arrived in Raymond on the 11th- and had been directed by General Pemberton to delay or repulse the Federal forces when they appeared.

Gregg headed south, to take a blocking position to thwart the advance. Pemberton had promised cavalry to scope the enemy’s movement, though in the event, it was a dozen schoolboys that showed up, not something like John Singleton Moseby’s bold Rangers. Just kids.

A dozen kids. Jeeze.

We drove past the Confederate Cemetery in the left, and the three Civil War cannon perched on the edge of the light manufacturing are on the right where the Rebel batteries had actually be perched. Three guns. My reading claimed that during the fight, one of the guns had suffered a casualty killing the crew, and leaving only two to oppose the advance of an entire Union Corps.

It wasn’t that hot a day- almost the anniversary of the battle, but I felt a distinct chill. What is it like to know that you have been beat, and running makes sense, though honor keeps you in the line?

A little further down the road, the modern two-lane sweeps to the east, though it is clear that the original path of the road went much closer to a straight line south and connected to The Natchez Trace and ultimately back to the River.

My pal slowed the car, and parked it against a steel wire hanging from solid wooden uprights with reflectors to ensure the visiting public wouldn’t drive through and crash the marble memorial.

“This is not one of you marquee battlefields from back East,” said my pal, as we dismounted. “No Park Rangers and Smokey Bear hats. This is a purely local memorial. This is what the people of Raymond chose to save, and it is their money to preserve their memory that is what has been preserved.”

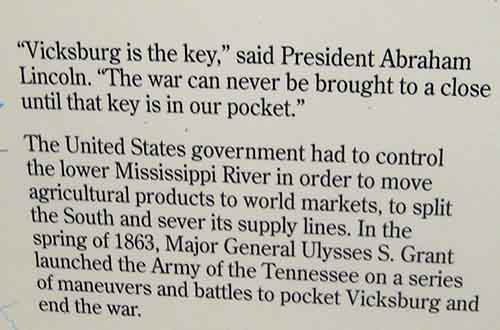

I marveled at it as my friend parked the car. There was an extended walking path with interpretive signage around a verdant green field. We looked at the marble monument that explained who had contributed to the preservation of the core area where the battle had been fought. We walked along the black-top walking path to the first interpretive sign. It featured a map of the engagement, showing who was where on the field.

My friend pointed to the little red box on the left. “That would have been the combined 10th and 30th Tennessee Irish,” he said. “That is where your Uncle Patrick was. We are standing about where the number “18” is on the old Port Gibson Road.”

I read a quote that was printed on the sign next to the map, from President Lincoln. It explained why this little place, for this day, was the deadliest place to be on earth. Raymond was the key to Vicksburg:

And that is exactly what we “Cool,” I said. “Let’s walk the field.” And that is what we did. More on that tomorrow.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

Raymond Days

It was Mother’s Day, and I was headed for Hinds County, Mississippi, coming up from The Big Easy via Bay Saint Louis on the Gulf Coast. I passed through Hattiesburg in the mid-afternoon where the two city police officers, one white and one African-American , had been gunned down the night before. Flags were at half-staff, but no other signs of disturbance were observable.

The reason for the timing of this jaunt was the presence of a old shipmate who has kin in the town of Raymond, and some of the attendant family business to be done. I had my reasons to see the town, and this was an opportunity that I could not pass up. The other odd coincidence was the date- the battle had been fought on the 12th of May, and the meteorological conditions on the field for the visit would be very similar to the ones that the soldiers experienced 152 years ago.

For those of you that care, the county was a product of western expansion in the first part of the new 19th Century, established in 1821 and named in honor of General Thomas Hinds. Specifically, I was headed to a Holiday Inn Express in Clinton, 7.1 miles from Raymond, since that is as close as the interstate and the modern version of civilization get to the place.

The land of Hinds County was graciously ceded to the United States by the Choctaw Indians in 1820. The subsequent economy was based largely on the plantation system and The Peculiar Institution, as well as proximity to the famed Natchez Trace that could be used to transport goods to the waterways.

Good order being important to any society that relied on that for economic activity, the Mississippi legislature provided for the selection of three commissioners to select a site for the courthouse and jail for the county, and to locate the same either at Clinton, or “within two miles of the center of the county.”

The Commissioners determined the center of the county should be its seat, and to be on Snake Creek. They named the site Raymond, for General Raymond Robinson of Clinton who gave up his prior claim to the land. The Court and Jail were appropriately sited, and the young town grew and prospered as a seat of justice for Hinds County. The courthouse, which remains an imposing Greek revival structure, was completed with skilled slave labor in 1859, and is now on the National Register.

In May of 1863, Raymond became a speed bump for Unconditional Surrender Grant’s army as he marched his army north through Mississippi to capture the strategic city of Vicksburg, center of rail and river communications to the South. On May 12, 1863, 12,000 Union soldiers of General James McPherson’s XVII Corps met the 3,000 Confederates of General John Gregg’s brigade in the Battle of Raymond.

I had kin there, as I have mentioned before, in the person of Great-Great Uncle Patrick, of the combined 10th and 30th Tennessee Irish. While in New Orleans the other day I was chatting with a physician- a dermatologist by specialty- who hailed from northern Mississippi.

He had been raised in Port Gibson, on the Mississippi, and we immediately began to talk about Grant’s line of advance from there to the northeast toward Raymond, attempting to finesse the approach to the ultimate objective, Vicksburg. The War- you have to capitalize it, in my mind- is never that far away in places like this.

Following the Union victories at Grand Gulf and Port Gibson, Grant was using the Big Black River, a place my new friend had grown up hunting, to protect Major General John A. McClernand’s corps on the Union left.

Imagine the formation of twelve thousand men advancing across the fields and through the trees. The actors included the rock stars of the ultimate Victorious constellation advancing across the fields and farms and hamlets, living off the land and devouring all in their path.

Lt. General U.S. Grant in command . Major General William T. Sherman in the center. Major General James B. McPherson on the right. Grant planned to strike the Southern Railroad of Mississippi between Vicksburg and Jackson and isolate Vicksburg by cutting Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton’s lines of supply and communications.

I knew all that, generally, but when I pulled up at the Clinton Holiday Inn Express I discovered that my pal had completed his business for the day at the hospital and was waiting to show me the town of Raymond, and the fields where General McPherson’s XVII Corps collided with Confederate forces collided with Brigadier General John Gregg’s veteran brigade in the valley of Fourteen-mile Creek south of town.

We exchanged handshakes, and the skies were clear with a few puffy clouds. “Perhaps we should go to the battlefield now. I drove through some fierce weather on the way today. Might be better to do it with salubrious conditions.”

“Great idea,” I said. “Let me check in and dump my bag.”

I walked into the lobby and presented my credentials to Tiffany behind the counter. She conceded that I indeed had a reservation, but that regrettably, the room was not ready just yet. I glanced at the clock behind the desk. It was almost five- odd not to have the beds made that late in the booking day.

But considering that I could profitably fulfill another mission and the delay was no real inconvenience, I shrugged, took my room access cards and went back outside to join my friend.

“Let’s go,” I said. “Do you mind driving?”

He didn’t, and as we covered the seven miles toward Raymond and began to slip into the past. We discussed the mutable nature of time and its application to society in northwest Mississippi. We stopped on the road to look up a leafy lane at a stately ante-bellum house.

“Grant stayed there one night, before heading off to Champion Hill. It is called Waverly. It was the plantation of John B. Peyton.” We continued on past much more modest homes owned by the descendants of those who had been enslaved there.

(St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, the Courthouse and the water tower are the landmarks of downtown Raymond, Mississippi).

We took a loop around the downtown, past some preserved old homes and St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, which had been used as a hospital by the Union when they routed the Confederates. The ladies of the town had lemonade and lunch for their Rebels, but in the event, the boys were moving too fast to get away and it was the Federal Troops who got the lemonade.

“You can still see the blood stains on the church’s floor from that period,” my friend said.

“Uncle Patrick talked about that. He came back to town after his Colonel was shot dead, and carried the body back here for burial.”

My pal nodded and then we turned right at the water tower and headed south toward the battlefield.

Tomorrow: Gregg’s assault and the fall of Colonel McGavock.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

VE Day

I was seated directly under the 500-pound bomb on the trapeze release under the Douglas Dauntless SBD dive-bomber the Navy taught Dad to fly down at NAS Pensacola. He told me the principle was fairly simple. Pop the big speedbrake flaps with the circular holes in them, point the nose of the airplane at the target and drop the bomb where the nose of the plane was pointed. Retract flaps and zoom away.

I hoped nothing was going to happen like that this morning, and that the aircraft riggers had done their job well. I don’t think I ever asked Dad what the aviation cadets in Pensacola thought about VE Day, and it didn’t occur to me when I had the chance. The Navy pilots all knew where they were going, and the fight in the Pacific was still going hot and heavy, and the prospect of invading the Home Islands must have filled them with dread.

I didn’t ask Mom, either, and she would have seen the crush of the crowds near where she worked for The Texas Company in the iconic art deco spire of the Chrysler Buidling in Midtown Manhattan. I don’t think we thought about what the news must have felt like that Hitler was dead and the Germans had quit the fight.

The Museum President’s secretary is Erin, and she was seated behind me. I turned around and we chatted as we waited for Dr. Donald “Nick” Mueller to welcome the crowd to the memorial service, she explained the delicate process of bringing the crown jewel to the Boeing Pavilion: up above the dive-bomber and the P-51 fighter and the Helldiver torpedo plane was a completely refurbished B-17 Flying Fortress. It literally obscured the ceiling of the glass-fronted soaring space.

“The bomber arrived on seven or eight trucks. They had to remove one of the wings to clear the catwalk so visitors can see it close up. And then they had to reassemble it after they hoisted it with several winches. Dr. Mueller said it was attending the birth of a child.”

“I believe it. This whole complex is extraordinary,” I said. “It is a collection that rivals the one at the Air and Space Museum downtown in Washington. Maybe not as broad, since the airplanes are all World War Two vintage, but this is amazing!”

“We started mostly with American airplanes, but there is a nice Supermarine Spitfire over in the other building.”

“I am looking forward to seeing it all- the Pullman rail car like the ones the G.I.s all traveled on, the armor and vehicle collection, the uniforms and artillery. This is incredible.”

Dr. Mueller looked out on the crowd and got up and walked to the podium to give us some worlds of welcome to the Freedom Pavilion’s Boeing Center. “Seventy years ago today in a red brick schoolhouse in Reims, France, a delegation of Germans arrived to sign the instrument of unconditional surrender to the Allies. The terms of the treaty went into effect a minute before midnight, and Europe, after six blood-soaked years of conflict was at peace. A peace,” he added with solemn gravity, “that has continued to this day.” He glanced down at the program. “I am going to introduce our Master of Ceremonies, Bill Detweiler, He is a consultant for our Military and Veteran’s Affairs Division, and he will call for the Colors to be paraded.”

He nodded at Bill, who took his place at the podium. Then he looked to his left and called out: “Sergeant, parade the colors!”

Four soldiers in crisp dress blue uniforms, two with rifles and two with flags between them marched to the front of the rostrum with measured cadence and on command, turned to present arms. I saluted, since an Act of Congress gave veterans the right to render the hand salute rather than place hand over heart even when out of uniform. The Army flag was dipped below the National Ensign, which stood alone and tall.

Once the National Anthem had been played, Bill took over from Nick and introduced CAPT Stephen Shaw, USN, the Force Chaplain of Marine Forces Reserve in New Orleans gave a quiet but forceful prayer of remembrance. The hall was still.

We all said “Amen” when he was done, and Bill took the podium once more to give us a preview of what we were going to see. “First, our Senior Director of Research and History and Samuel Zemurry Stone Fellow Dr. Keith Huxen will give us the historical perspective on what the significance of VE Day means, and what happened at Ike Eisenhower’s Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces in the hours before dawn, seventy years before.

Ike didn’t attend the signing. He paced and smoked cigarettes until General Jodl had signed and was ushered down to see him. “Ike looked at him, and told him he was holding Jodl personally responsible for full compliance with the terms of surrender and then dismissed him. Then Ike made the radio broadcast of a lifetime, informing the world that as of that moment, the mission of his Command was achieved.”

The Professor went on to talk a little about what the world might have looked like if the Allied had not prevailed- Hitler’s vision for a happy Aryan Master race re-populating Eat Europe and ruling over Slavic slaves. Sterilized slaves. It was a sobering idea, hearing what the Nazi vision had been.

The crowd was silent when he was done. Then Bill took over for the heart of the program: the testimony of three people who were there on VE Day: A Vet, a Home Front defense worker, and a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto.

Introduced first was Bob Wolf, who had been an infantry soldier in Germany not far from Hitler’s Alpine Retreat. He described the sense of relief that suddenly came with the wary hope that every road junction was not pre-targeted by artillery to blow him to smithereens, and that every bend in the road did not come with an ambush by machine-gun armed SS Troopers.

They celebrated by getting a local guide to take them in the woods, where they shot a couple deer and ate well. The next day they ventured to Hitler’s compound, where the buildings above ground had been thoroughly trashed by Allied air strikes. “The tunnels below were in good shape, though. There was a whole city down there, guard-posts and meeting rooms and bedrooms. And the wine cellars. Very large wine sellers. Our problem was that the 101st Airborne had been there the day before, and there wasn’t a bottle left!”

Bob was followed by Gene Geisart, a defense worker who collected and sorted scraps at a plant near his school. “I can’t tell you much about VE Day,” he said. “I finished school and went over to the plant and worked my shift. Everyone was asleep by the time I got home. So I missed it. By the time VJ day came around, I was in the Navy and we were deployed in the Pacific, so I missed that one, too. I am still happy they both happened.”

Both Gene and Bob received warm rounds of applause after their testimony. Then Bill introduced a petite woman named Ann Levey, who was of such diminutive stature that she had to bend the microphones down almost behind the podium. Her voice was soft, but we could hear every word.

“I was a little girl in a Jewish family,” she said on only mildly accented English. “We lived in Poland and escaped the Warsaw Ghetto. My family worked hard to keep us hidden from the Nazis. It was not a good time to be a Jew in Poland. When we were liberated by the Russians, we realized they were no better than the Nazis, and my parents vowed to get us out to the West. We walked to the Czech Border where we heard there were American soldiers. We made contact with them and explained our situation, and the G.I.s got us on a truck going west to the American Zone in Germany. They were the first soldiers I had ever seen that I was not afraid of.”

We were DPs- displaced persons- for a year before we got on a boat to come to New Orleans. We became American citizens, and my children are American citizens, and that is what VE Day means to me.”

She got a standing ovation when her remarks were done.

Bill closed it out by reminding us that because the war in Europe was over, that did not mean that huge sacrifices did no remain ahead. The Empire of Japan was likely to fight to the bitter end, and hundreds of thousands of casualties remained to come.

So despite the enormous significance of this day, there was still the end of it all to come. He talked about the plans to observe the real end of the World War- VJ Day, Victory over Japan. He introduced s fellow named Andrew Boyd, who manages a web site called NOLA.com and is the picture editor for the Times-Picayune. He called up a remarkable image on the two gigantic video screens on either side of the rostrum. When the residents of St. Roch Avenue heard that Japan had surrendered, they did what comes naturally to any New Orleanian: They held a parade.

Boyd talked about the man who took the picture with his Speed Graphic camera, Times-Picayune photographer Oscar Valeton, Sr., who captured the impromptu jubilation. His picture sat atop the front page of the newspaper the next morning, which was designated V-J Day. “We are trying to find all the people who are in the picture, and get them to come back to the Museum here on August 15th for the celebration of the final end of the war.”

Bill thanked him, and he thanked the speakers, and he thanked us for attending as he ended the ceremony. People began to get up and start wandering through the galleries, but I took out my Android phone and sent myself a text message: “Be in New Orleans on August 15th.”

It was a grand ceremony in a grand museum. Lest we forget, you know?

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

Victory Day

I was in New Orleans on the 70th Anniversary of Victory In Europe Day. I was at the ceremony to mark the occasion at a remarkable place, the World War Two Museum. I had a chance to meet with its President and some senior staff about what is coming next for what they call “New Orleans’ most popular museum, and #4 most popular in the Country!”

But more about the VE Day Memorial in a moment, since I am still writing on Victory Day, due to the quirk of dateline and Soviet insistence. General Alfred Jodl appeared just before dawn at Ike Eisenhower’s Headquarters in Reims, France, to sign the instrument of unconditional surrender to the Allies.

Hitler was dead, a suicide at the Fuhrer Bunker in Berlin. His successor, Gran Admiral Karl Donitz, had hoped to limit the terms of German surrender to only those forces still fighting the Western Allies. But General Dwight Eisenhower demanded complete surrender of all German forces, those fighting in the East as well as in the West. If the Germans provide intransigent, Ike was prepared to seal the front, and force all German surrenders to be to the hated Red Army.

Jodl radioed Donitz with the terms, and Donitz ordered him to sign. So, under the gaze of Russian General Ivan Susloparov and with the signature of French General Francois Sevez, and General Walter Bedell Smith for the Allied Expeditionary Force, Germany had officially thrown in the towel. Ike did not atten, pacing in his office and chain-smoking. Fighting would still go on in the East for almost another day. But the war in the West was over.

Since General Susloparov did not have explicit permission from Soviet Premier Stalin to sign the surrender papers, even as a witness, he was quickly hustled back East-into the hands of the NKVD never to be heard from again. General Jodl, who had been wounded in the assassination attempt on Hitler on July 20, 1944, would be found guilty of war crimes at Nuremburg for crimes against humanity and was hanged in October of 1946.

He was granted a posthumous pardon in 1953, after a German appeals court found him not guilty of breaking international law. It was important to the family, I suppose.

Anyway, prior to becoming a non-person, General Susloparov had no authority to sign for Uncle Joe, even as a witness. Accordingly, the Kremlin decided to call the German instrument of surrender at Reims a “preliminary” act.

The surrender ceremony was repeated in Berlin on 8 May (9 May, Moscow time) and was executed by supreme German military commander Field Marshall Wilhelm Keitel and Marshal of the Soviet Union Georgy Zhukov with minor Allied representatives in attendence.

That is why Russia and most of the former Soviet republics commemorate Victory Day today, and why I am technically accurate in saying I am not writing late about VE Day.

It is still Victory Day.

In Washington yesterday, there was a massed fly-over of the Capital by formations of war-birds amassed in theme formations, starting with P-40 Warhawks with fierce tiger mouths painted on the nose to commemorate the fighters at Pearl Harbor. The Warhawks first flew in 1938. Last in formation, of course, was a B-29 Superfortress, which first flew in 1942. The B-29 signified the Enola Gay and Bockscar Super Forts that ended one era and began another.

Some of them staged out of T.I Martin Field down in Culpeper, so I was torn. But the invitation to attend the Memorial Service at the Boeing Pavilion was too significant to pass up in the Crescent City. That is why I found myself in seersucker suit and bow tie in the front row of white chairs, seated directly under the 500-pound bomb attached to an SBD Dauntless Dive bomber- the very kind that Dad flew in the last days of the War.

It was a big day at the Museum. Sunny and humid, of course, but temperatures were in the mid-eighties and it was quite a pleasant day. Most of the tourists were in extreme casual attire. I discovered that dressing up is still appreciated in the South, and I got a lot of smiles. I made a note about that, as I made my way around the parked armored vehicles in the permanent collection. It is all quite remarkable.

I should give you a little context about the history of why and how the Museum came to exist, and why it is in New Orleans. That requires a little note about Andrew Higgins and his remarkable boat.

He is not an old-money product of Cajun society, though he might well be one of its most memorable. His father was a Chicago journalist who moved west to Nebraska to raise his family. He died in an accident when Andrew was seven, and the boy knew early on that he was going to have to shift for himself. At one point he was expelled from school for brawling. Despite being ready with his fists, or maybe because of it, he gained a commission in the National Guard, serving in the infantry and engineers.

Exercises on the Platte River got him into thinking about how to move people and equipment in shallow water, and he moved down the river, eventually setting up a lumber import-export business in New Orleans.

As part of the enterprise, he acquired a boatyard and in the mid-1920s began to produce innovative designs with recessed propellers that were highly maneuverable, with a “spoonbill” that enabled them to be beached and backed off the shore with ease and operated nimbly in the flotsam environment of the lower Mississippi.

Higgins called it “the Eureka Boat” and it quickly became the work boat of choice on the river.

He held onto the shipyard when the lumber business died in the Smoot-Hawley tariff Wars that helped usher in the Great Depression, but the shipyard- now Higgins Industries- continued operations. The Coast Guard recognized the utility of the design, and the Marines were interested as well.

Still, there was a problem for military and commercial applications: getting men and machines out of the cargo area of the boat required clambering over the gunwales or getting a crane to lift a vehicle something that was clearly impractical in a combat situation.

That is something that had occurred to the Japanese as well, and their solution to operations at Nanking in 1937 as they invaded China was to install a ramp that could be lowered at the bow of their boats.

American observers in Shanghai reported the development back to the States, and Higgins had a eureka moment. He ordered a prototype mocked up on one of his Eurekas and tested it on Lake Pontchartrain. It worked marvelously, and the modified design was designated the Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel, or LCVT.

It was more popularly known as “The Higgins Boat,” and it changed history.

Higgins Industries became one of the biggest companies in the world. At its peak, it employed more than 80,000 workers, with total government contracts valued at more than $350 million. Remember, that was when a million bucks meant something.

During World War Two, more than 96% of all Navy hulls were Higgins Boats. Ike Eisenhower said: “Andrew Higgins won the war for us…if Higgins had not designed and built those LCVP’s, we never could have landed over an open beach. The whole strategy of the war would have been different.”

Hitler knew it, too. There are those who memorialize Henry Kaiser and his Liberty Ships as the most innovative ship builder in history. I don’t think that is true. Kaiser industrialized a process that made a signal contribution to the war effort. But what he did was build ships faster than the U-Boats could sink them.

The Higgins Boat were transformative and changed tactics, and made it impossible to stave off a widely distributed assault on places like Gold, Juno, Sword and Omaha Beaches.

Adolf bitterly called Higgins the “New Noah.”

And that is why Stephen Ambrose, an acclaimed popular historian and professor at the University of New Orleans decided that a National Museum devoted to the D-Day invasion could have no better home than the one that produced the Higgins Boat. New Orleans.

Ambrose’s work with D-Day veterans, inspired him to initiate fundraising by donating $500,000of his own money to build “a museum that reflected his deep regard for our nation’s citizen soldiers, the workers on the Home Front and the sacrifices and hardships they endured to achieve victory.”

Along the way, he collected the earnest efforts of his colleague, Dr. Gordon “Nick” Mueller, the support of several significant grants from the Federal Government, the State of Louisiana and show business luminaries like Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg. In 2003, Congress designated the museum as “America’s National World War II Museum,” and let me tell you, it is something to see.

I will have to tell you about Victory in Europe Day tomorrow, I guess.

Damn, it was cool. But more about that later.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303

Spartanburg

It was almost noon before I could extricate myself from the farm. It had started to rain just when I was going to cut the front yard and ensure that the place didn’t look abandoned, so I thought I might get to make a pass with the Turf Tiger before the 0900 conference call, but I walked out on the front porch and things were still soaked.

The conference call spun into something- and if I was going to cut the grass and get clippings all over myself, I needed to shower after that, and when I actually got down to the barn to fuel and fire up the Tiger I saw that the pastures were so proud with the ferocious green growth that if they were not severely chastised, it was entirely possible that they would be uncuttable when next I had a chance to confront them.

So, it was noon before I got rolling, and the GPS attempted to vector me to I-95. I refused, and took US-29 south, through Charlottesville, Lynchburg and Danville before finally hitting the North Carolina line. The old road still goes through a lot of places, and it is a much better and textured drive, seeing where people live and shop and worship.

They apparently still do that stuff out here. I listened to the radio, and can recite the events of the manic news cycle almost by rote, the minutia of which I will not trouble you. I think there are two kinds of citizens these days- the ones of who are so immersed in the turmoil and chaos that they are near apoplectic (either side of the culture wars, pick one) or completely oblivious to everything.

The miles rolled by with only two minor safety issues on the US route, and one after I picked up I-85 and began to flow with the faster North Carolina NSCAR wannabes near the speedway at Charlotte. I was sympathetic to the last- an older fellow who was driving thirty miles below the posted limit and punched up his emergency flashers when he saw overtaking traffic looming in his rear view.

The new tires on the Panzer are a grand thing. The old man was acting like I did when I had to drive slow with the temporary spare on the right rear wheel last week. Sometimes you have to be the hazard, you know.

Judge lest you be judged, I suppose. Or let those with poor tires cast the first stone. But the slowness with which my synapses processed the event led me to suspect that six PM was probably about as late as I could trust my body, and started looking for acceptable lodging.

I tried once after a fuel stop near the hamlet of Cowpens, site of the 1781 victory of the Continental Army over the forces of the King, and a key tipping point in the re-conquest of South Carolina by the Patriots. I was interested, since I had steamed in the same battle group as USS Cowpens (CG-63) but never knew much about her provenience. It is pretty cool.

(Battle of Cowpens, 1781. Painting by William Ranney. The scene depicts an unnamed African-American soldier (left) firing his pistol and saving the life of Colonel William Washington, mounted on the white horse at center).

Exit 78 was much more welcoming, which is how I came to be sitting here dining on some pretty good scrambled eggs and a turkey patty.

I recommend the New Asia Cafe, if for some reason you swerve off the interstate here any time soon. Not bad, and better than my local Chinese-American delivery place in Arlington.

Life on the road, you know?

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303