There is nothing like walking a battlefield to understand what happened on it. The terrain is all, an imperative you can only feel with your own legs, and marvel at what was expected of the legs of ill-fed people in heavy woolen uniforms on a humid Mississippi day. And add the realization and the simple fact that a watercourse can provide an opportune trench of opportunity, and overwhelming force, can impose the will on the unwilling.

My dual purpose for being in Raymond, Mississippi, was to see my pal (I mean, how often do we find ourselves I Mississippi at the same time?) and to find where Great Great Uncle Patrick had performed the acts that gave him the Civil War equivalent of his fifteen minutes of fame, and try to understand it. We were there in Raymond, almost on the actual anniversary.

We turned south under the shadow of the water tower and headed south, the diametric opposite of the direction from which U.S. Grant and two Corps of Union troops came. Confederate General Gregg and his forces had arrived in Raymond on the 11th- and had been directed by General Pemberton to delay or repulse the Federal forces when they appeared.

Gregg headed south, to take a blocking position to thwart the advance. Pemberton had promised cavalry to scope the enemy’s movement, though in the event, it was a dozen schoolboys that showed up, not something like John Singleton Moseby’s bold Rangers. Just kids.

A dozen kids. Jeeze.

We drove past the Confederate Cemetery in the left, and the three Civil War cannon perched on the edge of the light manufacturing are on the right where the Rebel batteries had actually be perched. Three guns. My reading claimed that during the fight, one of the guns had suffered a casualty killing the crew, and leaving only two to oppose the advance of an entire Union Corps.

It wasn’t that hot a day- almost the anniversary of the battle, but I felt a distinct chill. What is it like to know that you have been beat, and running makes sense, though honor keeps you in the line?

A little further down the road, the modern two-lane sweeps to the east, though it is clear that the original path of the road went much closer to a straight line south and connected to The Natchez Trace and ultimately back to the River.

My pal slowed the car, and parked it against a steel wire hanging from solid wooden uprights with reflectors to ensure the visiting public wouldn’t drive through and crash the marble memorial.

“This is not one of you marquee battlefields from back East,” said my pal, as we dismounted. “No Park Rangers and Smokey Bear hats. This is a purely local memorial. This is what the people of Raymond chose to save, and it is their money to preserve their memory that is what has been preserved.”

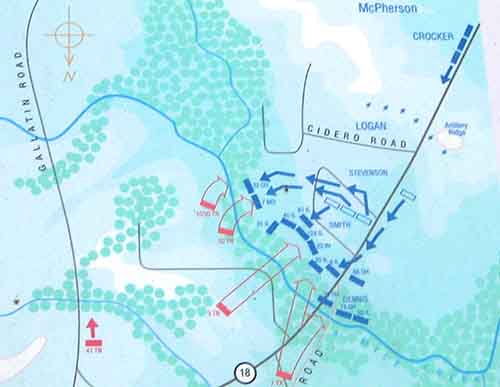

I marveled at it as my friend parked the car. There was an extended walking path with interpretive signage around a verdant green field. We looked at the marble monument that explained who had contributed to the preservation of the core area where the battle had been fought. We walked along the black-top walking path to the first interpretive sign. It featured a map of the engagement, showing who was where on the field.

My friend pointed to the little red box on the left. “That would have been the combined 10th and 30th Tennessee Irish,” he said. “That is where your Uncle Patrick was. We are standing about where the number “18” is on the old Port Gibson Road.”

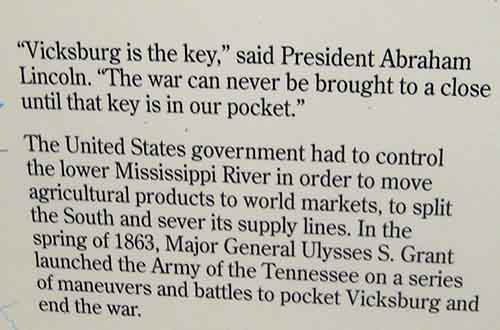

I read a quote that was printed on the sign next to the map, from President Lincoln. It explained why this little place, for this day, was the deadliest place to be on earth. Raymond was the key to Vicksburg:

And that is exactly what we “Cool,” I said. “Let’s walk the field.” And that is what we did. More on that tomorrow.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303