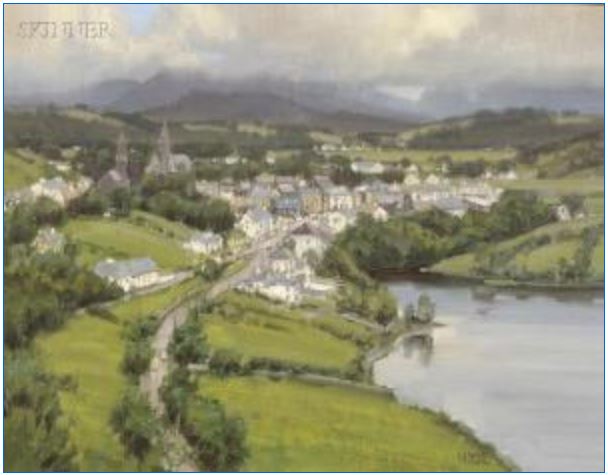

(The Village of Clifden, in County Galway, where Honora’s odyssey began. The blue eyes in the family came from the Viking raiders who harassed the coast of Ireland in olden days. Original oil by Wayne Wolfe).

AUTHOR’S NOTE: As it turns out, this voyage along the river of history has been quite an eye-opener. I had never thought much about Great-Great-Grandfather’s Civil War Service- my cousin Harold and I had come to the same astonished realization that he had walked away from the Union Army- deserted- just a couple weeks apart at the National Archives. That was truly remarkable- with credentials to prove we were researchers, we put in a request to see his service record, and they located it and delivered it to us on our separate visits in a little wire basket in less than an hour.

When I manage to compile all this material, I swear it will make sense, and even feature a love story, not just the thunder and bluster of war. And so, before the morning gets completely away from me, here is the tale of my Great Great Great Grandmother, and how this all came to be.

I had the most extraordinary dream last night, vivid beyond belief. There was a fair amount of stuff in it that was mildly interesting, to me, anyway. But the most vivid moment was the encounter with my Mother’s ghost. I could see every line in her face and the pale blue of her eyes, which like mine are the color of the sea. We talked briefly- she did not appear to know that she had passed- but was concerned with how everyone was doing.

It was good to see her, since this is the only means I have to interact with her on this side of the River Styx.

As I set up the mobile office the next morning, waiting for the Dazbog Russian-roast coffee to kick in, I marveled at how real it had seemed, I sipped coffee and thought of her, and her Irish family. They were railroad and river people. Since I recently traveled in the Great State of Mississippi to investigate the scene of conflict where my ancestors fought, I thought I might account for how the extended family flowed down to the Gulf.

Sorry for the timeline being in such a jumble. Eventually we will put it back in something like a coherent order for the book version, though I think the chapters have stood fairly well together on their own.

As I mentioned a couple times on this search for roots along the river, James Foley was my great-great-grandfather. He married Patrick Griffin’s sister, Barbara, in 1864.

It is another wartime story, but this one is not tall tales of cannon-fire and contraband and courtly Colonels, but of the sacrifice of women, who bear the special burden of coping with the madness of the men around them.

Author and historian Becky Black has touched on the story of Honora McDonough, Patrick’s mother, and her amazing trans-oceanic adventures. Becky was mostly interested in Patrick, since his account of the battle at Raymond is one of the most vivid around, and possibly some of it is true.

Having walked the field almost on the anniversary of the fight, it is intensley real to me now.

Honora’s story is just as amazing, but we only have the outlines of it. She married Michael Griffin, Pat’s dad, in Clifden, County Galway, Ireland around 1843. They had four children: Patrick being the eldest and Barbara the second of four. She was the “little mother” to the two younger ones, Mary and William.

The three oldest Griffins departed County Galway as the Famine rose to a peak in 1847, and things were at the worst. On one day alone in that awful year, 160 corpses were picked from the Galway County roads. On another, in November of 1848, 240 died in the Clifden workhouse.

The Griffins were not alone in hunger and the desire to get away from the crushing poverty. All that could flee to the boats in the harbor did so. Honora’s brother Patrick McDonough went off to America as part of the diaspora. Fourteen years later, he wound up a sailor, in service to the Union, on an iron-clad on the Mississippi. It is said that when the war was finally done, he was married in New Orleans, the amazing Creole city at the end of the fabulous Mississippi River.

Our Irish were junction-people, living where the waters and the rails came together.

To escape the troubles, the Griffins left the younger children behind with Mary, Honora’s mother, who kept a small hostel. (She lived to be 111!). They fully intended to return when the bad times at home were over, and Michael and Honora sternly informed mother Mary that they did not want their daughters to wed while they were gone. Little Barbara listened, and younger Mary did not.

Knowing she would be disowned if she began keeping company with a likely young lad, she ran away, hopefully with her suitor, and was never heard from again. Her woman’s story may have led her to America, too, but that branch of the family was sundered forever, and some say she is buried in Irish soil.

Honora and Michael wanted to recover their children, and perhaps take over the hostel. But sunstroke felled Mike in his tracks as he worked on the railroad in Tennessee. He died at Cedar Hill, and Honora abandoned the idea of returning to Ireland. She married a fellow named Thomas Griffin; no relation to Mike, and a perplexing problem in the disparate family archives. She had two children by him; Martin, who lived until 1910, and Myles, who was “lost at sea,” date unknown.

Barbara was fifteen in 1860, and determined to get her mother’s blessing, came to America to get that and find a husband.

She must have been a tough cookie. She said “farewell” to her grandmother and brother and crossed the Atlantic on her own. She landed on the Eastern Seaboard, possibly at Alexandria, and arrived in Nashville in time to spend the war years there.

No one knows how or where, but in 1864, she hooked up with Yankee soldier James Foley, a strapping young blonde with a ruddy complexion who was flush with cash from his part-bonus, and on veteran’s leave. He had concluded his first three-year enlistment in the Union Army, and re-enlisted under great pressure.

Barbara must have had a way with words the same way Patrick did. She convinced James to desert, and not to return to the 72nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. The records say he went missing in Cincinnati.

Because he was technically a deserter, he never filed for a pension, and never was a member of the Grand Army of the Republic, the VFW of the day. But he did live to a great age, not passing away until 1922, the year after his Rebel brother-in-law Patrick.

Honora lived with Patrick and Barbara, by turns, after her second husband died. In her declining years, she loved to walk, though she was bent with arthritis and was compelled to use crutches. She died at the ripe age of 88, in a home for the aged and was buried by her brother Patrick’s son, a Mr. McDonough, “who owned the funeral home from which she was buried.”

The family records say she was short and stout; light complexioned, with a square face. You can see some of that in the period picture of her son Patrick in his uniform of the 10th Tennessee Irish. Pat’s Dad, Mike, by contrast, was the very personification of the Black Irish: dark-completion, with dark eyes and black curly hair. He is said to be buried in St. Michael’s Cemetery (Catholic) six miles outside of Cedar Hill.

After the War ended, and Patrick’s great adventure came to a close, he married Bridget Welsh. They had five children together, including Louisa McGavock Griffin, born on April 10th, 1876, and last-born Walker E. Griffin, in 1880.

He continued the Irish tradition of arms, and served in the Spanish American War, and honored his father by naming one of his sons, born in 1902, Patrick M. Griffin.

After Bridget passed away, Patrick married the melodically-named Annie Deane Breene. They had two children together, and Patrick passed away on June 5, 1921, in the house he built at 300 12th Ave, South, in Nashville. He was 77, and told a good tale to the day he died.

That is when Louisa McGavock Griffin took the place over, and stayed until 1951, when she retired to be with family in Mississippi. It is gone now, as best I can tell from Google Maps, and the area has been mostly flattened by urban renewal and a modern building sits on the site. It is only two blocks away from McGavock Street, named for the Colonel who died in Patrick’s arms.

The other Griffin daughters, allied with the Piggotts, Smiths and Martins of Tylertown, Mississippi, southwest of Hattiesburg, almost all the way to Louisiana. They made their homes down the river through the 20th century, and right into this one.

If I can find the time in semi-retirement, I will visit the places that James Foley’s and Patrick Griffin’s descendants call home. It’s a family affair, after all.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303