Editor’s Note: This is powerful stuff from shipmate Marlow. I was in attendance for the ceremony and reading this still moves me. Hard.

-Vic

Author’s Note: I didn’t begin to write about these events until May of last year — their 30thanniversary. Here is the current quasi-organized version of these thoughts.

-Marlow

In a New York Minute

Times change. Time moves slow then fast.

So does life.

Like in a New York minute.

In other words, instantly.

I laid down and dropped off into a deep sleep after a 12+ hour long day of high-speed driving home, woke up at 4:30AM with a chilled, light filled flash, sat bolt upright briefly in bed scanning the dark room, and then drifted off back to sleep. And life as I knew it ended.

Awakened by loud 7:30AM knocking on the front door accompanied by some obnoxious CB radio chatter in the background, I hurriedly put on a robe and stumbled down the stairs to see what was the matter. Sitting in his squad car, a cop had a mike to his lips, saw me approach, stopped his radio report by turning the barking voices on the other end off.

Just the merciless facts.

Those had been my stock in trade for almost twenty years and were the approach to delivering both good and bad news to bosses, peers, and those you lead.

Those four words describe the words the officer spoke to me. No contemporaneous notes survived on how his words changed everything in life that May morning.

It was extraordinary since there would be no forgetting his words or the moment. I thanked him and looked briefly up at the sky before hurrying inside to dress and begin my in-person notifications.

Only in retrospect did I sense that the utter ordinariness of that dark night and blindingly bright blue skied sunny morning.

The stark commonness of this brief info transaction helped insulate me from truly believing it had happened, let alone getting past it. I recognize now that there was nothing unusual in this: confronted with sudden cataclysm, we all focus on how unremarkable the circumstances were in which the unthinkable occurred, the clear blue sky under which a mountain boulder rocketed down from the heavens above to crush my soul. Yet a diarist would have opened the day’s notations “Monday, May 21, 1991, dawned temperate and cloudless over the nation’s Capital Beltway burbs.”

“And then — gone.”

In the midst of a full-on life I was deep in death. I repeated the details of what happened to everyone who didn’t know the facts whom I came into contact with in person and over the phone at our house, the funeral parlor, the church, her graveside and so on during those first weeks — friends and relatives who brought food and made drinks and laid out plates on the dining-room table for however many people were around at lunch or dinner, all those who picked up the plates and froze the leftovers and ran the dishwasher and filled our home with love and compassion.

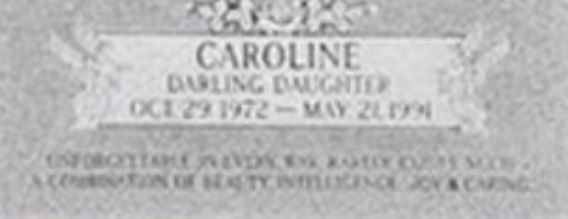

I have few memories of telling anyone the details, but I just know that I did. It had come from me — my 18-year-old daughter’s messenger of death by car accident coming home after her freshmen year of college to the impending wedding of her just graduated older sister as her maiden of honor.

It is now, as I begin to write this, this mid-May morning of 2021.

I We got through the ensuing week of mourning and her burial at Arlington National Cemetery. A joyous wedding took place on time 12 days after her burial.

Then the house nest went empty. And the mourning began in earnest.

Health issues exploded — pneumonia and deep depression, shock, arriving in parking lots with no known connections to the day’s chores or work.

My attempt to make sense of the period that followed, weeks and then months cast me adrift from my past ideas about death, illness, about probability, risk and luck, about fortune both good and bad, children and memory, about grief. I was utterly clueless. I had never dealt with the fact that life ends and how shallow and tempestuous the sea of sanity I had been sailing on. Same went for life itself.

Oh — the paperwork and the waiting kept my body busy but my mind was a blank, my soul was on empty. Pity — constructive but unhealing.

I recall sitting in lots of empty rooms. They were cold, or I was. I wondered how much time had passed between the event and now. It often seemed no time at all had passed — maybe a maximum of several minutes.

Four months later, I nearly committed myself to a rubber room while aimlessly babbling during a scheduled ortho doctor’s visit at Bethesda Naval Hospital until I finally got a hold of myself and sought treatment in a grieving support group.

I was finally starting my long journey back.

But first I needed a drink. At home. In the afternoon. In my uniform of the day.

I sat on the living room couch and began my search for help by calling the county’s mental health line.

Several spot-on options.

I changed clothes and started planning dinner. Outdoors on the shade treed deck. BBQ. Store-bought sides would be fetched.

After initially stressing about the menu and the aging, balky gas grill, an exceedingly rare-during-the-past-few-months moment of calm descended. The fog that had rolled in and blinded me would clear, eventually I thought, but not before bumping into more things that exquisitely hurt and disoriented me. This was my candle-lighting-in-the-darkness day of a sort. As the meal’s items cooked and the table was set, I had a second drink before sitting down to dine.

Talking and making sense began — haltingly but it had started. Plans set.

The years of firsts and seconds followed. Anticipation of these days – birth, Christmas, passing her favorite snack in the grocery store and so on — proved more painful than the actual days or moments. Trying to straighten out in my mind what would happen next proved unhelpful — one day at a time became my mode of operations.

The year of seconds proved easier as it unwound, and understanding and acceptance followed.

Decisions that had taken forever then became faster and easier.

Going through her stuff that she had in her purse at the time of death — driver’s license, a VISA card, student ID card, cash – not much IIRC as she was a hand to mouth type. I recall calmy combining her cash with the cash in my wallet, taking special care to interleaf her fives and ones with my fives and ones. This was six months after she passed. In her bedroom that was slowly being put back in order — she was an inveterate dirtbag like her old man.

Five months or so after group therapy session attendance started, I drove the hundred or so miles north to where she had died. Outside of its pitch-black nights, nothing remarkable was evident. No marks or scrapes visible. Just two endless strips of asphalt with drivers going 80+ mph east towards DC or west to the Midwest.

I had authorized over the phone an autopsy report — never felt the need to read it.

Driving fast. Falling asleep. Going even faster. At night. In the darkest section of I-70 in Maryland. Driver’s side window wide open. Rollover. Three times. Dead at the scene.

(Thus read the brief handwritten notes on the officer’s notepad. He had more to say from his Q&As with his shift chief before his visit with me.)

In a New York minute — gone.

Yet, her front seat passenger and fellow student — uninjured and alive.

Both were seat belted.

Were there any portents? Books said there were. None have arisen thus far 30+ years later for me.

I wondered if she had any.

And even then — gone.

Grief, when it comes, is nothing we expect it to be. It sucks.

My 1990s grief was not what I felt when my parents died 20+ years later, both after some years of increasing debility. I finally understood after two decades the cosmic one liner joke – “in birth, two people go into a room and three come out, while in death one person goes in and none come out.”

What I felt in each of my parents’ instances was sadness, loneliness, very little regret for things unsaid, and helplessness for the pain and physical humiliation they each endured. I and my siblings helped them as best we could as one of us was always there 24/7 for their last years. I understood the inevitability of each of their deaths.

The earlier death grieving process was a whole other deal, setting off reactions that surprised and crushed me like a submarine silent on the ocean floor, getting pounded by ever closer and closer depth charges.

Grief waves obliterated the dailiness of my life — tightness in the throat, gasping shortness of breath, Jesus — sighing out loud in public while in uniform, and the often-empty feeling in my gut.

Had I eaten was a question some of my shipmates started asking me from time to time. After three months I had lost serious weight. So, I made checklists to ensure proper sustenance.

I could deal with the autopsy request by the cops on the day of her death, but the notion of an obituary was an absolute knife plunge into my heart when it was surfaced at the funeral parlor the following day. Picked out a standard form, filled in some details and let it get launched. Got the hell out of there pronto.

The only thing I did that had long-term meaning to me during that first week was picking and playing Sweet Caroline on a boom box under my chair as the mourners processed away from the grave site.

Grief turns out to be a thing none of us know until it slams into us. We do not expect its shock to be utterly destructive, dislocating to both body and soul. We might expect that we will be prostrate, inconsolable, crazy with loss. We do not expect ourselves to be literally crazy, yet outwardly cool disbelieving customers. My pre-death version of grief was “healing” and possessed of a forward movement. BWAHAHAHAHA.

The worst days will be the earliest days. Not.

I imagined that the moment to most severely test me would be the funeral, after which this hypothetical healing would take place. Not even close.

It was about seemingly endless nothingness. As the universe was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be . . .

My former world without end had ended.

Meaning in the repeated rituals of my pre-loss life came back slowly. Cooking. Shopping. Laundry. The smell of clean sheets and deli counter at the commissary . . . . Those fragments of driftwood accumulated around me and slowly shored up my ruin . . . . so much so that contemplating the swell of clean water rising in my kitchen sink one day before washing the dishes was a singular moment of progress from way down in my grief hole.

Life returned but was different. I learned to enjoy what I had when I had it.

Finally.

Copyright 2022 My Aisle Seat

www.vicsocotra.com