(Elizabeth Cochran Seaman at rest in Mexico in 1885, and before she became a false mad-woman and then world traveler. This is how our family borrowed her pen-name “Nellie Bly” for our Elizabeth, who carried the name all of her life- and ours!)

All right, we want to continue the story of how the greatest female Stunt Journalist of her time got her pen-name appended to our Great Aunt’s life. Our Aunt Bly wasn’t an author, but she was an adventuress just the same.

We just knew her as a woman of prim passion who knew the previous few generations of the family. But naturally, what surprised us yesterday was the story of the woman whose name the family adopted for her. We knew her as “Aunt Bly,” and the woman from whom the name was helped change the 19th Century into the 20th.

One of Nelly Bly’s several biographers tried to sum up her role in the 1994 book Nellie Bly: Daredevil Reporter by Brooke Kroeger, emeritus professor of journalism from New York University. She did it more eloquently than we can try this morning. As a woman in modern journalism, Brooke tried it this way:

“(Nellie’s) two-part series in October 1887 was a sensation, effectively launching the decade of “stunt” or “detective” reporting, a clear precursor to investigative journalism and one of Joseph Pulitzer’s innovations that helped give “New Journalism” of the 1880s and 1890s its moniker. The employment of “stunt girls” has often been dismissed as a circulation-boosting gimmick of the sensationalist press. However, the genre also provided women with their first collective opportunity to demonstrate that, as a class, they had the skills necessary for the highest level of general reporting. The stunt girls, with Bly as their prototype, were the first women to enter the journalistic mainstream in the time.”

This is how Nellie’s name was adopted- or imposed by our Aunt Bly. At the Dispatch, she was relegated to stories about fashion, the home, and women’s issues, as was expected for female journalists at the time. However, she grew bored with day-to-day newspaper life and took an assignment to go to Mexico.

She was only 21 years old at the time and travelled with her mother across the southern border into Mexico. She spent six months there, sending reports home about the government and culture.

Six Months in Mexico was the book she wrote after her travels in about 1885. At that point she had become dissatisfied with the strictures imposed on female writers and her examination of cultural issues described the lives and customs of the Mexican people and the poverty of the commoners. What she observed was recorded with the zest and insight for which she became famous.

In her journey south of the Border, Nelly was struck by the widespread addiction to playing the Lottery, noting that people would even pawn their clothing in order to finance purchase of tickets. Other major traditions and customs were examined with an independent female view. Those included public smoking, courtship, weddings and the legend of a plant called the “maguey,” the base root from which pulque and mezcal were made.

In an electrifying analysis of the habits of solders, she included their preference for the use of marijuana to relax after hard days marching, training or fighting. In an eerie bit of time travel, she noted that the Mexican troops rolled the leaves into small cigarros and smoked them to gain an intoxicated state that lasted most of a working week.

She described a process to the smoking similar to one still in use as what we knew as “Shotguns.” In that process, the smoker takes a puff and blows the smoke into the mouth of the nearest man, who inhales it. That gesture would continue around the circle until the troops were all intoxicated and would remain in that state for days.

But culture and social behavior was not the only landscape on which she reported. The Mexican government was then ruled by a dictator named Porfirio Diaz. Sensitive to oppression, Nelly reported on the imprisonment of a journalist for his journalism, but returned to the United States fearing she might be likewise jailed for critical opinions of the government.

Though glad to be home, Nellie’s adventurous spirit could not last another year at the Dispatch in Pittsburgh. In March 1887, someone on the newspaper staff found a note from Bly that confidently declared, “I am off for New York. Look for me.”

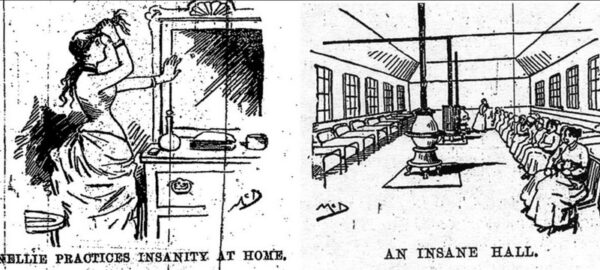

There was going to be a lot to look for. Arriving in The Big Apple, Bly got a job writing for the New York World, a major Democratic newspaper owned by the dynamic publisher Joseph Pulitzer. Her time at The World was initially marked by her break-out story which gained her fame. In New York there were stories of abuses being imposed on women confined to the city’s psychiatric ward. In order to investigate the stories thoroughly, she faked a mental illness to be admitted to the Women’s Asylum, located on dry land in the river now known as Roosevelt Island.

In preparation, she stayed awake one night to enhance a disheveled demeanor, and was judged by three men- a cop, Judge and doctor- to not be in her right mind. She was shipped over and admitted to the Women’s Asylum. After staying there for 10 days, the World demanded she be released.

Back at her desk in the bustling city she wrote a best-selling report on the terrible conditions she had discovered within the Asylum. She called it: “Ten Days in a Mad-House.” Her feat was a sensation and began the tradition of the “stunt girls,” female journalists who covered stories with themes that still resonate today. They were often about social injustice issues then that are still unresolved today.

This was a reversal of the traditional roles women filled in journalism, and newspapers competed fiercely to see who could offer more astounding stories. “Ten Days” raised Nellie as a national star in her trade, but that naturally required more sensation to continue. The biggest of these came to Bly in her bed one night in 1888. She brought the idea to her editor the following day: suppose she were to travel around the world? If she could do it in less than 80 days, she would improve upon the fictional adventure of Phileas Fogg!

The idea was clearly a winner, but the struggle about who would conduct the contrived journey for The World raged for months. She could only speak English, would have to be escorted by a man, and being female, would obviously pack too much luggage to make good time. The World editor even suggested sending a man on the much-ballyhooed trip instead. Nellie angrily declared, “Start the man, and I’ll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him.”

Discussion on timing for the journey would take a full year, but eventually was resolved on a November day in 1889, for Nellie’s timing to be determined. Her editor asked if she was prepared to depart within days.

Nellie Bly naturally said “Yes.” Our Bly would have said exactly the same thing. We will have to tell you about that tomorrow!

Copyright 2023 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com