4100 Nebraska Avenue

I was on a roll yesterday and actually read a book to try to get ready to tour guide the Australian delegation down to Nebraska Avenue. Between that, and the interesting relationship between the Nebraska Avenue Complex and Arlington Hall Station just across Route 50 from Big Pink I was so saturated with World War II spookery that I could not get my arms around the whole matter of 4100 Nebraska Avenue.

The ground rules for the Delegation, back when we were in the concept phase, was to get a van, equip it with beverages, and go for a spin around some of the Intelligence Community sites. The original OSS-CIA complex on Hospital Hill by Foggy Bottom; show where the Soviet intercept officer used to park in front of Main State to copy the transmissions of the bug microphone in the conference room. Show them where the disgruntled Pakistani Mir Amar Kazi gunned down CIA officers arriving for work. The site of the original National Photographic interpretation Center over the car dealership where the Soviet Missiles were identified in Cuba and the sprawling campuses where the ODNI and the NCTC hang out- that sort of thing.

It would have been fun, but the bus didn’t happen and I had to plan an alternative on the fly that relied on Metro. That is why I picked Nebraska Ave, since that had a couple sites so close that it was un-escapable. The house at 4100 Nebraska Avenue had it all.

That brought Arlington Hall Station back in to the picture, since it was Soviet codes that were broken there that caused Soviet double Agent and First Secretary of the British Embassy to leave the country. I didn’t have time to get into the Cambridge Five yesterday. The penetration of the British and American Governments is an interesting story, but I am not going to get far down that road, or avenue as the case may be.

The Five, composed of the four certain ones (Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, Donald McLean and Anthony Blunt and perhaps many more) had a connection to the well-built house on the corner lot that we would walk right by on the way to the NAC. All four men were active Soviet Agents during WWII, though not in Washington. Philby was posted to DC after the war, where he was the liaison officer to the FBI and the newly-established CIA. In that capacity he was a visitor to Arlington Hall Station, where he was briefed on an exceptional penetration of the usually excellent tradecraft of the KGB.

The program was called VENONA, and I have mentioned it before. Suspicious of Uncle Joe Stalin and the possibility that he might seek a separate peace with the Nazis, the Signals Intelligence Service (Later the Armed Forces Security Agency and then NSA) at Arlington Hall began to work the encrypted message traffic sent by the Soviet Diplomatic and intelligence services. This message traffic was encrypted by means of a normally secure one-time-use key code. The messages were copied and stored at the Hall, and the body of traffic was worked for nearly forty years due to one significant vulnverability.

Due to a serious blunder on the part of the Soviets, some of this traffic was vulnerable to cryptanalysis. The Soviet company that manufactured the one-time pads produced around 35,000 pages of duplicate key numbers, as a result of pressures brought about by the German rapid advance on Moscow during World War II.

Hundreds of Soviet Agents were unmasked- including the Alger Hiss, the Rosenbergs and the Cambridge Five. The existence of VENONA was still a deep, deep secret, and its existence was not permitted to be used at the trials.

(Harold Adrian Russell “Kim” Philby).

Anyway, that is where the house at 4100 Nebraska comes in. Philby and his family arrived in Washington in September of 1949. In September 1949, the Philbys arrived in DC. Ostensibly, his posting was as First Secretary, but he actually was the MI-6 station chief and responsible urgent and top-secret communications between the United States and London, as well as “more aggressive Anglo-American intelligence operations,” like the ones that attempted to land agents in denied areas like Albania. The operations always seemed to fail, which led the Americans and Brits to conclude that the Communists were too effective to continue.

However, a more serious threat to Philby’s position had come to light through the VENONA decryption program. Donald McLean had been assigned to the Embassy until shortly before Philby was posted there. This was no small deal. Donald Maclean had been Secretary of the Combined Policy Committee on atomic energy matters. He was Moscow’s main source of information about US/UK/Canada atomic energy policy development, and reported on its development and progress, particularly the amount of plutonium (used in the Fat Man bombs) available to the United States. Maclean’s reports to his NKVD handler on the relatively small amount may have emboldened the Soviets to arm Kim Il Song’s North Korea, and to blockade Berlin.

The VENONA intercepts indicated someone in the Embassy was passing secrets to the Soviets. The intercepted messages revealed that the British Embassy source (identified as “Homer”) travelled to New York City to meet his Soviet contact twice a week. Philby had been briefed on the situation shortly before reaching Washington in 1949; it was clear to him that the agent was Maclean whose wife, Melinda, lived in New York.

The investigation into the British Embassy leak was an ongoing affair. Guy Burgess arrived in October of 1950 as a hard-drinking and flamboyant gay man, who Philby invited to live in the basement of the house at 4100.

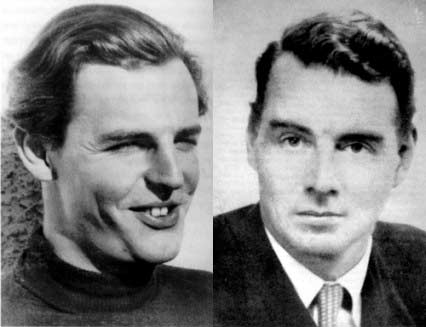

(Donald McLean (left) and Guy Burgess).

Mind you, Philby knew what was going on at the Naval Security Group just a block up the street at the NAC, and hence Burgess did as well. It is a curious coincidence of proximity, though of course there are no coincidences in this life.

Meanwhile, Guy’s life was unraveling, and he raised the hackles of everyone he encountered. Philby’s second wife Aileen resented him and disliked his presence in the stately house. The local Yanks were offended by his superior airs and contempt for every aspect of American society. J. Edgar Hoover complained that Burgess used British Embassy automobiles to avoid arrest when he cruised Washington in pursuit of homosexual liaisons. His personal disintegration was disrupting life in the Philby household.

The morning after a particularly drunken party, a guest returning to collect his car heard voices upstairs and found “Kim and Guy in the bedroom drinking champagne.” They had already been down to the Embassy, but being too drunk to work had come back to the house at 4100 Nebraska Avenue.

Burgess was a problem for Philby, but concluded that Burgess could not be left unsupervised. The situation was tense. Maclean had been identified as the prime suspect in the Embassy leak and was under surveillance by MI-5. Philby decided that Burgess should return to London to warn him that it was time to flee.

Burgess had a solution to a quick exit from the States: he managed to get nailed speeding (at 80 mph) three times in just one hour, poured a plate of prawns into his jacket pocket and left them there for a week. He was casual in the handling of classified documents at the Embassy, and since arriving in Washington he had been almost continuously intoxicated.

Burgess was recalled from the United States due to “bad behaviour” and upon reaching London, warned Maclean. They disappeared from the UK in the early summer of 1951, around the time I was born. They eventually surfaced at a Moscow press conference five years later.

The British embassy was in a secret uproar as news spread that not one but two senior Foreign Office officials were probably Soviet spies. Philby broke the embarrassing news to the FBI, and told his colleagues at the Embassy that he was going home for “a stiff drink,” which is exactly what I would have done in his position. Instead of opening the bar at 4100 Nebraska Avenue, though, he headed for the potting shed, collected a trowel and walked back to the basement where Burgess had been living. He retrieved from behind a loose brick the Russian camera, tripod, and film given to him by his Soviet handlers, sealed them in waterproof containers, and placed them in the trunk of his car. Then he climbed in, started the engine and drove north.

Philby had traveled the road to Great Falls many times, and used to drink at the Old Angler’s Inn along the way. The road had little traffic in those days and was heavily wooded on each side. On a deserted stretch he parked, removed the parked, extracted the containers and trowel, and headed into the trees. He emerged after a few minutes, casually doing up his fly for the benefit of any passersby who might question what he was up to.

The camera may still be out there, a silent monument to the Soviet spies of Washington, who once lived at 4100 Nebraska Avenue.

As it turned out, a logistics snafu caused the tour to be cancelled. Too bad. I had really hoped to tell you the story. So, I climbed out of my presentable clothes, got back into my damp swim suit and returned to the pool, located conveniently near Arlington Hall.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303