General Quartering

Nagato’s appearance had been altered from her usual configuration when Ed Gilfillen first saw her. He said that camouflage was the key to try to distract the American pilots. To render her less conspicuous, the tops of her mainmast and stack had been cut off and plywood structures erected on her decks. Rust blended in with the forlorn hills ringing the Yokosuka Ko, but a few patched of brown, green and black paint were added. No doubt she was difficult to see, but the July raiders of 1945 found her and scored two major bomb hits.

Just before hostilities eased, her crew left her, abandoning ship, so to speak.

They may have looted her as well, though much food was left aboard After that, she was systematically exploited by various American units who took even her electric-blue plush upholstery and smashed what they could not carry away.

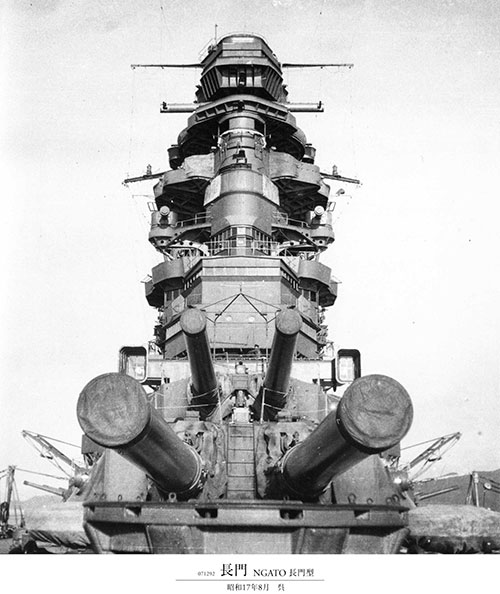

Seen from a distance, Nagato had a low, rakish and characteristically Japanese profile which gave her something of the appearance of a submarine. The resemblance was not wholly by chance; the designers had put most of the bulk of the ship below the waterline where it could not be hit by naval gunfire. It was also reflected in her trimming gear. Instead of flooding tanks on the opposite side to trim, as a surface ship normally does, she blew her tanks on the same side like a U-boat. This has the disadvantage of requiring dangerous high-pressure airlines but it cancels loss of buoyancy due to a hit instead of doubling it.

Her freeboard was less than that of any American ship of comparable size. Later, we were to put her lee rail underwater like a racing yacht. Hers was a fierce, grim outline—not a nice thing to see looming through the mist.

Her main decks were wood laid on steel. The space forward of the number one turret was devoted to anchor gear as in our naval ships. The system was so simple that one man could perform the sea and anchor duty without assistance, if need be. The system was so rugged that it could go without maintenance for long periods. From two holes in the deck, the chains came up around power capstans that gripped them, routing them straight forward to great steel nostrils in the bow.

Puttering about the forecastles in the gray light of early morning, I used to marvel at these chains, for every link weighed more than a hundred pounds. This fact was to be brought forcefully to my attention several times during the last cruise of the last capital ship of the Imperial Navy.

Standing in the eyes of the ship with your back braced against the wind, you could appreciate the sweep of the deck back to the muzzles of the guns with the squat turrets behind them.

From there, you might glance up to the slotted steel box from which the Admiral and the Captain used to watch the course of battle. Behind that towered the pagoda, mighty in its complexity of detail: battlements, , cat-walks, bridges, guns, range-finders, revolving anti-aircraft turrets, radar search-lights, signal-yards and platform upon platform piled up for 150 feet. Inside the pagoda was a mass of switchboards, offices and living spaces, every compartment with an oxygen bottle for protection against gas attack.

There even was an elevator to take the Admiral as high up as he wanted to go.

The heart of this edifice was the conning tower already mentioned, a steel box with slotted walls a foot thick. One entered through a bank-vault style hatch. The narrow windows had been cleverly places to give an unobstructed view three-quarters of the way around the compass. Inside were a steering wheel and gyrocompass repeater, the engine room telegraph and dials to show the speed of the ship, what the engines and rudders were doing and where the guns were pointed On the port side- the place of honor in Japan- was the Admiral’s upholstered settee. Few Americans could stand upright in the conning tower, but otherwise it was roomy. From the back wall was a cluster of speaking rubes and telephones that led to all communications centers in the ship. The tower had taken a direct hit from a heavy bomb without any of the instruments being damaged, In the heat of battle, the occupants may not have even noticed the explosion.

Most of the arrangements about the ship were conventional reflecting British practice more than the American style. Baths were special- there wasn’t a single shower in the ship. Instead, there were burnished copper tubs so deep you could sit in them on a little wooden stool and just peep over the edge. In this fashion the Japanese sailor takes his scalding bath. In Officer country the tubs were single. The crew had bigger ones, ten or more bathing at a time. Sanitary arrangements were of all sorts, from high stools one had to climb up on through scuttled to the old-fashioned benjo toilets.

Room furniture was like that of a passenger liner of the 1920s, including polished metal wash-bowls that folded away out of sight when not in use and which drew water fro a tank that had to be filled by a steward. There was no piping of any sort Interior decoration was along somber British lines; oak panel effects were so cleverly painted on molded sheet steel that you had to tap to be sure what was real wood and what was not.

Wood and metal were, in fact, mingled throughout the design, with the more easily fabricated material being used for each part, Drawers were mostly wood, panels were mostly constructed of metal. Bunks were arranged just the same way as in our ships.

Officers were served Japanese-style breakfasts- but European lunches and dinners. The men had rice with pickled rashes, canned fish, soy sauce and occasional delicacies such as salmon, crab meat or pickled tangerines. Apparently they ate where they worked and lived, squatting on mats behind gun shields or in the passageways. Food was fetched from the galley by one of the sailors in the duty section.

This system has many advantages. No one who has witnessed the chaos and confusion on US Navy ships when General Quarters is sounded at night will deny the strengths of this system. On our ships men come running half the length of the ship to their GQ stations. We used to say “All hands forward run aft, all hands aft run forward and all hands amidships block passageways.”

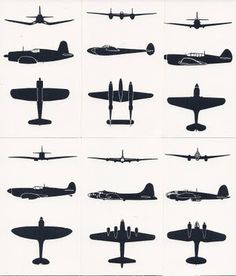

The Japs didn’t miss a chance for education: in their leisure time, the sailors studied silhouettes of American aircraft painted on bulkheads and gun-shield everywhere throughout the ship.

The officers lived in the extreme after-part of the ship on two decks: senior above and juniors below. Originally, these had larger port-hoes than any of our ships. These compartments very comfortable or even luxurious—truly pleasant places to live The Admiral’s mess was a large room extending right athwart the stern and had skylights and electric fans for ventilation, After of this was what we called a shrine room, also with a skylight and fans where pictures of the Emperor, Empress and Crown Prince were kept There was also a desk in this room, which was used only the Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Fleet.

Of course with the coming of war, the ports were sealed off, spoiling the whole effect. We used the Admiral’s mess as a wardroom, since Nagato’s original wardroom was completely destroyed by a bomb hit in July. But we wouldn’t have used it anyway, since it was a dingy, noisy place, cold in winter and hot in the tropics. All the officers would have gladly traded their traditional quarters for rooms up forward that still had their portholes for ventilation, but our sailors had got on board first, and it was wisely decided by Captain Whipple not to try to evict them.

The cruise south was going to be hard enough as it was. We didn’t need to add resentment to the challenge of learning how to operate a ship with all the instructions written in Japanese!

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicscotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303