Northwest to Northeast

(NE8 is in there someplace. I pussied out and did not dismount to find it. Next time will be easier, with a posse).

It was 2003 and I had changed jobs and was working on the SARS epidemic and the Anthrax attacks. The whole thing made people cranky, and I wanted to get back to looking for Stones.

It was a pleasant late spring day, and I took I-395 across town to hook up with I-295, thinking I could get around the Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens somehow. The gardens date back to an Act of Congress in 1926 that helped preserve the property of a fellow named Walter Shaw, who created a marvel of lily-covered water gardens out of an old ice pond on the flats along the Anacostia River. Some of his original greenhouses survive there, and it is worth a stop since this is a part of the District that is under-served by most commercial trade.

My Grandfather camped out on the Anacostia Flats with the Bonus Army in the early 1930s, but he was not particularly interested in seeing the sites. He and his buddies wanted compensation for their Service in the Great War before they were run out of town. There is no monument to them that I am aware of.

This is out of sequence, and I apologize. A decent account of the Stones would continue in stately order, just as Ellicott’s original survey team had done, marching relentlessly around the four sectors of the rectangle of the Federal Enclave. I had intended to continue on to the SE from the North Stone, but of course that had turned out to be the wrong one, and I had to go back and retrace my steps and that is just the way it went.

When I was able to get focused on the important things again, I figured I could follow Eastern Avenue directly southeast. I was tempted by the direct route, though, and succumbed to the temptation of Pennsylvania Avenue and its bridge across the Anacostia where the freeway ended back then, before all that stimulus money drove the interstate across the Anacostia. It was always a pain in the butt, as the freeway petered out at RFK Stadium and the right-turn onto Pennsylvania Avenue. I waited three series of traffic light changes, only ten or fifteen minutes since traffic was light.

Then onto I-295 to Eastern Avenue and the great barrier to L’Enfant’s precise grid of the floodplain to the north. I discovered that Eastern Avenue goes under the Anacostia Freeway and I would have to park the car and plunge up one of the three paths that lead to the stone. I didn’t like the looks of things. The descriptive literature informed me that at the intersection of Kenilworth and Eastern I should follow the trail that begins at a separation in the fence along the north side of Kenilworth.

“The trail immediately winds to the right, and then parallels another fence northwest along the edge of a gravel distribution lot. The trail forks when the gravel lot fence begins to turn to the right; turn left here. The left fork roughly parallels another fence and leads to the charred rubble of a former dwelling. The stone is along the fence to the right, about fifty feet before you reach the remains of the dwelling.”

It sounded appealing, assuming that I didn’t get jumped and the car was there when I got back. NE8 was going to be another problem Stone. This would be easy with a search party, and these days there is development and it may be a lot easier to find than it was then. I decided to knock off some easier ones and save the organizational effort to dragoon the manpower to find NE8 for the next attempt.

This was getting more complex than I had anticipated. The only way to go north and get across the Anacostia was to get back on the expressway and lose myself in a dizzying series of off-ramps until I found myself on Bladensburg Road, headed back west from Maryland. I intersected Eastern just northwest of NE7, the last Stone before the Anacostia Interruption.

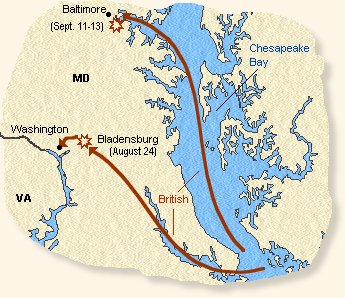

Eastern Avenue veers off to the southwest at what had been Fort Lincoln, near the high ground of Bladensburg where the Marines made their stand against the advancing Brits in 1814.

The Battle of Blandensburg is not much talked about these days, though there was a flurry of interest during the bicentennial years of the War of 1812. The crushing defeat of the American forces allowed the British to capture and burn the capital, something Jubal Early aspired to a few dozen years later. The unpleasant turn of events at Bladensburg has been termed “the greatest disgrace ever dealt to American arms,” so perhaps the less said about it the better.

You can take a pilgrimage to the visitor’s center at 4601 Annapolis Road in Bladensburg, if you want and get the details. The Brits has a pretty good time, from what I can tell, and the image of the Capitol and the White House burning is pretty stark.

Maybe as stark as looking across the Potomac with a icy-cold cocktail from the balcony of the Bachelor Officer’s Quarters at Ft. McNair a couple hundred years later and watching the flames leap up from the Pentagon. But as usual, I digress.

(Battery Jameson in the Fort Lincoln Cemetery, just up the hill from NE7).

The true line of the District now runs through the Fort Lincoln Cemetery.

It is a marvelous cemetery. The vista from the high ground was impressive. Management has preserved part of the Civil War rampart of the fort and there is the stunning memorial to the dead of the 1812 war. “Semper Fidelis!” reads the inscription. It makes you proud of the Marines who confronted the invaders. I suppose they are not remembered as well as their Shores of Tripoli comrades because the loss was so humiliating.

I looked around for a while, the monuments placid under brilliant blue skies with that hint of crispness in the air from the early season. NW7 is located along the fence in the cemetery’s Block 18, 75 feet southwest of the Garden Mausoleum near the Garden of the Crucifixion. It has had some recent repairs, though I don’t think the Brits did anything to it. Then I mounted up to drive out and get on Eastern Avenue, bound for the northwest.

I had street addresses for the next three stones, NE5, 4 and 3. They are in the yards of private residences, and were then still in their cages just as the Daughters of the American Revolution put them in 1917. It was a burst of patriotic spirit and thank God they did, else America’s first monuments would have disappeared as certainly as the markers to the District’s Glorious Dead of the First World War. I have heard that there is still one marker on a sidewalk, somewhere in the District, and if I ever get the fever to see more stones I will go track it down, as I will the markers for the Washington Aqueduct. Or the stones of the Mason-Dixon line.

Maybe I will try to find them all someday, if there is world enough and time.

But first things first.

Copyright 2016 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

twitter: @jayare303