The High Line

Editor’s Note: Alert readers will note that this is the conclusion of Mac’s mission to meet with Marshall Tito at the White Palace in Belgrade. Unknown to me at the time, our Legislative Affairs Den Mother Annie was a girl, living there with her family. Her Dad was one of the military attaches in the capital, and he played Starsky and Hutch games with his Jug minders as the Cold War settled in. It sort of reminds me of today. I will share his story with you one of these mornings.

– Vic

The High Line

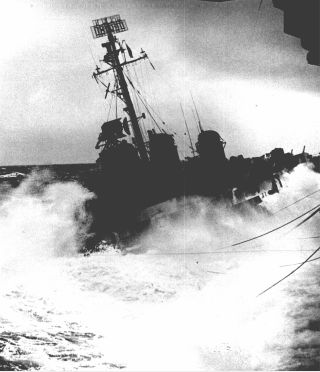

(USS Des Moines, CA-134, in rising gale. Oil painting.)

Peter is a real pro of a mixologist, and the heart of the spirit of Willow’s bar. He snuck up in his unflappable way and filled my tulip glass to the precise level for easy listening to Mac’s story of lunch with Marshall Josef Broz Tito, Emperor of the Balkans and the Dalmatian Coast.

“The weather was crappy,” said Mac. “But the Jugs were determined to get Admiral Gardner and our party back from Belgrade to his flagship in order to get the heavy cruiser Des Moines underway from Rijeka on schedule.”

“The port visit was scheduled for four days, and four days only. Tito’s people were very strict about that. With the ALUSNA on his way back to Washington on the early flight to receive his dressing down, we boarded the plane and waited for a break in the clouds. The wind was freshening, and when we got airborne, it was a short but bumpy flight.”

“If Des Moines left on the 23rd, she had plenty of time to get to her next appointed mission, which was a Christmas Day visit to Athens. The intent was to buck up the liberals, who were having their problems with the local Communists. 1952 looked to be an unsettled year in Greece, and the presence of the big warship was just the right statement about America’s resolve.”

Mac looked at his Virgin Mary a bit pensively, and stirred the concoction with the celery stalk that rose from the red depths.

“Sedans were waiting at the airfield and whisked VADM Gardner and our party back to Des Moines with time to spare, and check the block for “Mission Complete.” At least it was “MC” for him. Art Newel and I still had to get back to Naples in order to make the Holiday with our families.” He took a sip of tomato juice. “Therein lies another tale.

“The notes of the meeting with Tito merited our expeditious handling in order to get them to Higher Headquarters. Admiral Gardner was once more insulated by the blue-tile linoleum of the Flag Spaces on the cruiser, and the unusual intimacy with us required by the mission was abruptly terminated once we crossed the Quarterdeck of he big ship. The icy remoteness of rank and command were once more imposed.”

“I hear that,” I said, taking a long swallow of pinot. “Traveling overseas with Congressmen, I actually came to believe they were real people. Unreasonable, but real.”

Mac smiled. “Rank in the Navy, as you know, is a thing of wonder. We live in such forced proximity at sea that the barriers between us consist of vertical social stratification, from the mess decks north through Officers Country to the Flag spaces in the superstructure.”

“Des Moines had her engineering plant on the line in preparation for getting underway, and we pulled out of the old Italian port that had become property of the Jugs, and proceeded into the teeth of a rising gale in somber colors: gray skies; gray ship, gray sky, gray water topped by white foam. Despite her bulk, the ship moved around briskly in response to the power of the storm.”

“The warship was bound on important business for the United States; thus the need to get Art and me to the nearest friendly airfield at Trieste or further transportation to AFSOUTH Headquarters at Naples was only a tangential requirement that would be accommodated while underway to Athens.”

“We never got to that port in our Med Cruise on Forrestal,” I said. “I wish I could have gone to the Acropolis.”

Mac nodded, having been just about everywhere. “So, once in international waters, the cruiser hoisted ball-diamond-ball on the mast to signal ‘restricted maneuvering’ and set a course as steady as she could in the heavy seas. A plucky destroyer came alongside in the swells, and the deck party prepared shot lines to go across and set up a Hi-line transfer.”

“Oh man,” I said, taking a sip of Happy Hour white. “Once, out of boredom and curiosity, I stationed myself in the background as the bridge team aligned my carrier Midway to come alongside a fast stores ship for underway replenishment. We were going to take on provisions, fuel and ammunition through VERTREP- vertical replenishment- by helicopter and by underway replenishment direct from the stores ship via lines stretched between the ships. It took miles to set up the position properly, and the consequences of failure were grave for the hapless young OOD.”

“That is one of the things we do well as a Navy, and the Chinese and Indians will have to get good at, if they are to be real Blue Water navies. Without replenishment, the great ship lose their military value swiftly. I will bet that your UNREP was in the gentle swells of the Pacific.”

I nodded in agreement. “Smooth as silk and still hairy. I was standing behind one of the lines and a Chief yelled at me to get clear, since if the line parted, the bitter end would snap back and cut me in half.”

“As we closed, and the destroyer they were going to hi-line us to fell into formation, I could see the front third of her full coming out of the water alongside. Art and I were directed to the weather deck. I could feel the crackling tension in the deck crew as they prepared the shot for the messenger line. Art and I were in our Service dress blues with the gold braid on our combination covers pulled down as chin-straps to keep them from blowing away in the gale. We had our little duffels clutched to our orange Kapok life vests.”

(A Destroyer alongside for replenishment in heavy seas. Official Navy Picture)

“A rudder casualty or other navigational mischance would could the ships to plow into one another, and there would be hell to pay, at least for the destroyer. Damage and lost careers at a minimum, death maybe, with me or Art in the middle.”

“That day before Christmas Eve, only a hundred feet separated the two ships. The heavy cruiser at 17,000 tons displacement handled the rising seas well; the DD bobbed wildly, plunging in the waves. The process for us was the same as when the ships transferred inert mail and movies. First the deck gang fired the guns with the messenger line attached.

“One or two tries might suffice to get a line across. Sometimes, more attempts were needed. Once across, and assuming no one on the receiving ship actually got hit, the light steel line was hauled in and secured, followed by another, heavier line and rigged with the sling in which we were supposed to ride. The changing tension on the wire caused it to rise and fall like a yo-yo, sometimes dipping into the waves far below.”

“It was the only time I had to do it,” he said. “Thank God. It was a terrifying and foam-flecked adventure. Done expeditiously,” he said, “the evolution might take an hour in peacetime. There were those on the bridge of the cruiser who had done this in the war, when enemy aircraft might suddenly appear and they viewed this as an excellent opportunity for training the crew for emergency break-away. They hauled us with alacrity and a minimum of immersion, but it is not something you want to do while attired in Service Dress Blue.”

“The breakaway, once the transfer was complete, was done with élan. Not to mention relief on the part of the bridge team that could then concentrate on navigation without the consideration of having Des Moines cut them in two. The skipper on the tin can then could move on to the next item on the Schedule of Events, which was a brief stop at Trieste for fuel and to disembark me and Art. All business, no liberty for the crew.

“We snagged a driver and a duty car at Fleet Landing, and made our way to the airport, where a Navy Air Transport Service C-47 Dakota was to pick us up. Despite the weather, NATS made gave it the old college try. We could hear the engines of the transport at the appointed minute of its arrival, though that was as close as it could get due to the thick clouds over the field. There was no instrument assistance at Trieste, and the plane circled above in the thin gray light. There was no hole to pick in the thick gray wool below the Dakota, and no way to land safely.”

“The pilot was ordered to return to base in Napoli, sans PAX, and mission complete for him and his crew, if not for me and Art.

“For our part it was another ride in the duty car, this time to the train station in the old central city. The great waiting area was thronged with holiday travelers. At the ticket office we bargained in broken Italian and English for first class tickets to Roma, via Rapido, with onward transportation via the Metropolitana line to Naples. There was salt crusted on our uniform pants.”

“Seated in first class, we realized we were exhausted after the adrenaline rush of the hi-line transfer and the confusion at the airport, dress blues wrinkled, the overnight journey did not seem so bad. The rains had been awful that December, and the North of Italy was flooded. Shortly out of the station, we had one or two snorts from the bottle of brandy Art had secured while I negotiated the tickets. Then the brakes failed on the only first class car. The smell of burning asbestos pads filled the train, and with confusion and great show of energy, we eventually found ourselves in the only seats available, the hard wooden benches in the unheated Third Class car.”

“No amount of brandy could warm the seats, and the coffee we bought to doctor the liquor with was gone. Our blues, which had looked so trim and proud with Marshall Tito at the White Palace, were now wrinkled and our once-snowy white shirt collars were gray as the skies. We were looking pretty drab, only a day away from dining with the Ruler of all the Balkans.”

“We shivered through the night, passing through Rapido, where a dining car was added to the train.”

“An Italian businessman in a well-tailored car coat boarded the train there, headed for Roma, his mistress and his holiday, in that order. He looked us and took pity. “Ah,” he said in gently rounded English, “You are officers, and should not be in such conditions. Join me, and let us share this journey in a civilized manner! It is my gift to you!”

“In the dining car there was civilization aplenty: white tablecloths and heavy silver, gleaming china, steaming coffee and a breakfast that stretched elegantly into lunch, the waterlogged countryside in muted green rushing by, clickety-click.”

“Eventually the ancient ruins of the massive aqueducts began to appear, marching toward the Imperial City, and soon enough we were on the platform, watching our elegant benefactor disappear into the holiday throng, his smartly tailored overcoat draped over his shoulders, Continental-style.”

(Mt Vesuvius looms above Naples.)

“Another train, this one not so long, took us down to bella Napoli. The Bay was the color of gun-metal in the dying light, and Vesuvius loomed darkly under the low skies. When we pulled into the grand old pile of the train station, we climbed down off the train and walked out to the street, stiff, tired and relieved to be done with it.”

“I told Art I would see him at the headquarters in a day or so, and secured a cab. I directed the driver to the apartment block where I had secured a genteel residence for my little family. It was a curious place up the stairs that had seen better days, but it was good enough for us.”

“You said your had to purchase your own light and bathroom fixtures when you moved in?” I asked.

(Humpty Dumpty’s daughter, circa 1986. Copyright David Coleman 2010)

“That was just part of the merry anarchy of Naples. Those were the days when the original Humpty Dumpty sat on the wall soliciting business outside the base at Bagnoli, on the way up the hill to AFSOUTH.”

“She and her daughter were known to generations of sailors,” I responded with a shudder. “I may not have seen Athens, but I did see her.”

“Eventually the taxi wound its way through the traffic and pulled up in front of the apartment. I fished the last of my lira out of my wallet and paid off the cabbie. Then I trudged up the grand staircase to our place that looked down on the inner courtyard. I put my key in the lock. Inside, Billie had some holiday candles going and the place was warm. I sailed my combination cover across the room toward the chair near the coal fire. Sounds came from the kitchen that sounded like dinner, and a small voice could be heard yelling from the direction of the bedrooms.

“Billie,” I said. “I’m home! Marshal Tito sends his regards!”

Copyright 2016 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com