Jasper, Mush and Mac

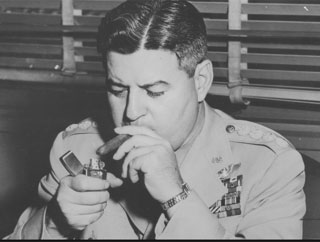

(Legendary skipper of USS Wahoo, LCDR “Mush” Morton)

I don’t think Lizzie or Meghan knew the details about the spy swap- the one in which a Russian sleeper cell of agents had been rounded up by the FBI, and ultimately exchanged with the Kremlin, just like the bad old days on that Bridge in Berlin.

Didn’t matter; I was not privy to the nitty-gritty either, and certainly the Admiral didn’t know. He was just back from the Outer Banks and a traditional summer week with his family at the beach.

The girls were more concerned with the growing anticipation about the final resolution of the Lebron James matter, which is much more important than a suddenly visible component of the secret world. I mean, the continued existence of Cleveland as a city was at stake, you know? It was more serious than someone uprooting the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and leaving town with it.

I was sitting at the corner of the Willow bar, just a few minutes early for my date with the Admiral. The girls were just getting settled at the end of the bar where old Jim normally holds court, pointedly drinking Bud in the upscale wine bar, and on the whole, I infinitely preferred the company.

Lizzie was a dark-haired beauty with an expectant look, no ring, and Meghan, ring, was a vivacious blonde.

The ladies arrived for a glass of wine, and a light snack from the neighborhood bar menu. As attractive as they were, I understood why Peter paid them special deference. Linen and pearls were the motif, and considering how sweltering hot it was outside, they looked cool and elegant.

(Russian Sleeper cell expelled in 2010. Ana Chapman at upper left became a media star back home).

It had been a busy day. The Russian spy ring had all pled guilty that morning in the Rocket Docket of Federal Court just down the Little River Turnpike from Big Pink that morning, and the lot of them, ten spies, spouses and kids, and were boarding a Vision charter jet headed for Vienna by the time the Admiral drove over from the Madison in his champagne Jaguar and parked at the curb in front of Willow.

I forget what I was doing, except I seemed to be on the phone a lot trying to find the services of a hydrographic engineer with a Top Secret Clearance and working knowledge of the Empty Quarter of Arabia. I made a note on the office pad to check and see if Vision was a wholly-owed subsidiary of an agency where I used to work or the other side. You never know when you might need a charter with a certain understanding of how things work.

Four alleged intelligence operatives were being processed in Moscow, but they had a shorter flight to Austria, and there was a lesser sense of urgency about it. I thought of my pal Ed, who had been detained by the FSB in some trumped-up charges for nearly a year when the kleptocracy was reasserting itself in the Kremlin, and on the whole, decided I was much better off in the commercial side of the business.

Of course, in this screwy decade, who knows what that is anymore? Except for the Jihadis, I forget who the enemy is. And Sara, the dark-eyed knock-out waitress from a Lebanese family, could make you forget about the threat from the Middle East in a heartbeat.

Then the Admiral appeared beside me, looking tanned and ready after his time at the beach. As we settled in for out interview, the spies were getting on planes, and we were about to talk about the targeting issue for the 313th Bomb Wing and the B-29 campaign against Japan.

But first I pulled a napkin off the stack to start taking notes, and borrowed a pen from the Admiral.

I told Meghan that she was sitting next to one of the people who made the victory in the Pacific possible, and that the Admiral had been part of code-breaking team that made the battle of Midway a winning proposition.

The Admiral leaned over and said that he didn’t think the ladies were old enough to know what the battle of Midway was, and Meghan sat up tall and took umbrage.

She certainly did know, and wanted to know precisely how the thing was done. The Admiral told her, and she looked at him with wonder. “Have you ever told that story before?”

He smiled, and his eyes twinkled behind his glasses. “Only about 10,000 times,” he said.

We all laughed, and the ladies eventually moved on to do something else while the sun was still shining, and the Admiral and I got down to the business of targeting the Japanese petroleum reserves, and the matter of why he is not entombed with “Mush” Morton and the entire crew of the USS Wahoo at the bottom of the La Perouse Strait, the northern entrance to the Sea of Japan.

This is going to take a minute, so you might want to go get a fresh drink.

The girls had been interested in whether we were married, being on the topic themselves, and Mac made quite an impression on Lizzie and Meghan when he announced that we were both eligible, not that they were. But being of the age when everyone seems to be pairing off, they were interested in all the possibilities.

Mac told the story of his beloved Billie, whose given name was Sarah, like the dark-eyed waitress who melts my heart, but who drops the “h.” She hovered down the bar beyond Peter as the crowd thickened, causing other males to ooze interest.

Mac told us that Billie’s Dad had been committed to the idea that she would be born a boy, and though it did not work out that way, he never stopped calling her “Bill.” Her friends softened it to “Billie,” and that is what Mac called her all through the marriage, and the long decline that she suffered, starting at the age of 59.

That got Meghan’s attention. Mac said he had three careers; one as a Naval Officer, one as a senior member of the Intelligence Community, and twenty years caring for Billie. It was an interesting perspective, given that the girls were just starting lives as married or about-to-be, and me dealing with what is happening with the decline of my folks back home in Michigan.

Mac has sailed through all the storms save the last and was bright as a new penny. It was with disappointment that we watched them leave; there was Liz’s wedding coming up, and the ladies were focused on the various errands they needed run to make the nuptials perfect.

Once they were gone and our brains could concentrate on something else we got down to the topic I wanted to address, which was his interaction with Major General Curtis “Iron Pants” Lemay.

The cigar-chomping XXth Air Force Commander on Guam was having trouble putting the Empire of the Sun to the torch in the winter of 1944 and the long, hot spring and summer of 1945. Mac had been part of a significant change in tar- get strategy that helped remove the Japanese sanctuary in the Inland Sea.

Mac told me the CINCPACFLT staff moved incrementally forward in January of the last year of the war., and there is a lot that I will need to get to, since it is related to the saga of Bill McCullough, and how he wound up there after the fighting stopped in August of 1945.

I have a dozen or more cocktail napkins piled up next to the computer about the bombing campaign, and the hidden story of the 313th Bomb Wing, but it isn’t that neat. In fact, it is as messy as the blurred ink on the absorptive paper. We had to pop back to Makalapa Crater, since that is where Jasper Holmes saved Mac’s life.

It is a little confusing, since Mac was there during the big war, and then back again as the intel chief during Vietnam, and I was there in the early 1980s. The blur of things and slow change of adamant institutions caused many more napkins to be covered with spidery diagrams.

If you are not in our little tribe, I will have to digress for a minute. Bear with me. Wilfred J. “Jasper” Holmes was an intelligence officer in charge of the Estimates Section of the Fleet Radio Unit Pacific (FRUPAC). The whole enterprise was about code-breaking, and was intensely secret. So secret that a special Army unit was established, controlled directly by the Joint Staff in the Pentagon, to control the distribution of the intelligence derived from it.

Mac was one of the handful of officers on Oahu who inter- preted and analyzed intelligence derived from the breaking of the Japanese naval encryption code designated “JN-25,” and handled by the ULTRA control system by the Army unit’s special security officers.

Holmes was neither a code- breaker- cryptologist, in the term of art- nor an intelligence officer. Jasper was an unrestricted line officer, a submariner, and had commanded S-30 at Pearl Harbor in the 1930s before severe arthritis put him on the beach in medical retirement. Jasper had an engineering degree and joined the faculty of the University of Hawaii. He also was facile with the typewriter, and was a published author in the Saturday Evening Post.

He was called back to active service as tensions rose in the Pacific. His natural aptitude brought him to FRUPAC and the Estimates Section, where his experience as a line officer would be best used to interpret what the code-breakers were pro- ducing. The alliance between submarines and spooks has been profound down the years, and most of us still have signed oaths in dusty safes that swear us to secrecy about the depth of it.

The Estimates Section was the first prototype of “all source” fusion intelligence that brought together the best information drawn from code-breakers, spies, aerial reconnaissance and operational reporting to determine the strength, composition and movements of the Japanese military machine as it stretched across the Pacific.

Mac was not an intelligence officer either. He had been commissioned as a deck officer, and was working as Deputy Fleet Intelligence by talent, of course, but in that position by the sheer luck of the draw.

Luck is a funny thing.

There were two elite groups who served as the poster children of glory for the war years. The first were the Fly Boys of both services, bombers and fighters roaring across the wild blue, silk-scarved and goggles against the foe.

The other was the Silent Service of the Pacific war, the submariners who took the fight to the Japanese when everyone else was falling back.

Naturally, Mac chafed a bit at staff duty, and by 1943 was interested in getting in the fight. Well, let me be a bit more precise. The earnest officers at the Hawaii Sea Frontier were periodically inquisitive why a junior Deck Officer appeared to have a cushy shore billet on O’Ahu while the war raged. Mac could not tell them what he was doing, and periodically, Jasper Holmes or Eddie Layton would have to reach out and say “Never mind.” Still, the Sea Frontier folks did have a point that Mac did not contest. The way things worked in those days was that the submarine force interviewed prospective officers sending them on a war cruise. Mac put in his request, hoping that a war cruise would put the matter of sea duty to rest, and was approved to join the crew of “Mush” Morton’s USS Wahoo (SS 238).

(Fleet Radio Unit Pacific, also known as Station HYPO, the code-breaking and intelligence station at Pearl Harbor).

Mac remembers the bold young skipper well. “He had he biggest hands I have ever seen.” Annapolis class of 1930, Morton was a capable and highly aggressive submariner with ice-cold seawater in his veins. Arriving at SUBPAC, he convinced Admiral Charles Lockwood that his next cruise would be to the Inland Sea to remedy the deficiencies of existing torpedoes with the new Mark 18 electric model that was still being de-bugged.

Wahoo departed Pearl Harbor on September 9, 1943 with a mixture of each weapon.

She left without Mac. Jasper Holmes decided the day before sailing that impending Japanese operations in the Solomons required the most experienced analysts to be at their desks supporting Estimates, and he turned off Mac’s orders.

Jack Griggs was the Wahoo officer that Mac was supposed to replace, and he missed the deployment, too. There was not enough time to find a suitable replacement, and the sub left for the SOJ with her wardroom one officer short.

Mush topped off fuel tanks at Midway Island, and proceeded west to enter the Sea of Japan via the northern neck at the La Perouse Strait around September 20th, and patrolled below the 43rd parallel for about four weeks. The Estimates section at FRUPAC followed his progress in the usual looking-glass manner: based on Japanese navy internal reporting.

Wahoo was able to sink four ships in the area, including the 8,000-ton steamer Konron Maru, which sank with a loss of 544 souls. The other three ships that Morton sank totaled 5,300 tons.

Mush Morton and his 79 crewmembers were never heard from again. Japanese reporting indicates he tried to break out of the SOJ via the La Perouse on the morning of October 11, 1943. Why he chose to make the run on the surface is unknown, but possibly associated with combat damage.

A coastal artillery battery engaged Wahoo, and later patrol aircraft and surface units piled on as Mush took Wahoo below, trailing an oil slick. A submarine chaser arrived in the vicinity and dropped 16 depth charges. An expanding sheen of diesel fuel two hundred feet wide and three miles long was the last thing anyone saw of Mush the Magnificent and the Wahoo until a Russian hydrographic crew surveyed the wreckage in 2006.

(Wahoo on the bottom at a depth of 186ft. Discovered by a Russian crew in 2006).

The loss of Wahoo sent shock waves throughout the entire submarine force, and Admiral Lockwood immediately ceased patrol operations in the Inland Sea. The Japanese then had that body of water as an effective sanctuary, at least until Mac had a chance to talk to Iron Pants Lemay on Guam 18 months later.

This is a complicated business, and was clearly going to take another session to unravel. I had a second glass of wine as Mac contemplated having another Virgin Mary, one of the special ones that Peter makes with so many vegetables that it is almost a salad.

“So,” I said. “Sixty-six years ago, if Jasper Holmes hadn’t stepped on your orders, you would have been bones at the bottom of the La Perouse Strait for seven decades?”

“Yep. Mush got the Navy Cross, posthumous. Jack Griggs and I lived. Luck of the draw.”

I was blown away by the revelation and took a sip of a lively white chardonnay that Peter recommended. “Submarines are still relevant today,” I said. “Did you hear that three Ohio-class boomers all showed up in Asia last week, appearing at Diego Garcia, Subic and Yokosuka? They have been modified to carry hundreds of Tomahawk cruise missiles. It was a signal to China, I think, and a warning to the North Koreans over the sinking of that destroyer.”

Mac smiled a thin smile. “My sources say the signal didn’t work. The big exercise that the Fleet was going to conduct in the Yellow Sea was moved to where the Chinese told us we could operate.”

“So the Chinese are telling us where we can go in international waters?”

“Appears to be true. They have established a sort of Red sanctuary, like the Japanese did in the Inland Sea in 1944, I guess.”

I shook my head. Where is Iron Pants Lemay when you need him?

(USS Wahoo Memorial overlooking the La Perouse Strait).

Copyright 2017 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com