Foxing the Sun

Editor’s Note: The ladies from Massachusetts made it to Arlington some time long after I was asleep at the farm. The plans to get them a parking pass and the keys to my unit worked, according to Donna this morning, who cheerfully rang me up to dispel any misgivings. She and her pals were going to take an Uber tide to the big Women’s march, and according to sources who have reported reliably in the past, there were many females on the streets of Ballston with signs protesting the policies of the new Administration. I had checked the grounds at Refuge Farm on arrival the day before and saw no rioters, marching bands, or media commentators. The distinct lack of drama in the country was welcome after all the hoopla on inauguration Friday. I guess it is now on to the Next Big Thing. It is probably about how Jasper Holmes and Mac Showers felt in the aftermath of the big fight at Midway Island a long time ago. I hope this one turns out as well as that did, but we are kind of short on guys like Jasper these days.

– Vic

Foxing the Sun

(Old Japanese Comic Book, “Army of Mickey’s following the battle flag.” Image courtesy Jennifer).

The trick to understanding how Jasper Holmes foxed the Empire of the Sun is contained in the methodology they used to create OPINTEL. It was a fusion of methodologies: an ‘all-source’ approach to integrate communications intercept, code breaking, photographic, open source information, topographic, hydrographic and human intelligence, all cooked up in the processing unit of the Combat Intelligence Unit in the basement of Building One at the Shipyard at Pearl.

Of course, it started literally the day of the attack in December 1941. Commander Joe Rochefort was Officer in Charge (OIC) of the Radio Intelligence Unit (Station HYPO). The riddle was wrapped in an enigma as is common. The whole thing was covered by the euphemism of the CIU.

Mac told me at the Willow bar that the Navy cryptanalists were not able to read operational Japanese Navy message traffic- the JN-25 code system at the beginning. Jasper Holmes had made some progress tracking merchant ships, the information on which was available though Lloyds before the war swept all the commercial activity into the levee en mass war efforts of the respective belligerents.

Mac joined Holmes and his two yeomen in February, by chance, and some significant progress had been made, though trial and error. Joe Rochefort was to devote all his efforts to breaking the JN-25 code, and enlisting the support of the growing mountain of cross-indexed messages to glean the true meaning of each five-digit code group within them.

Once enough sense was made out of an intercept, it was turned into actionable information to support the pencil annotations on the daily onion-skin overlay that went to Admiral Nimitz each morning, and to transmit to the Fleet.

“That is pretty crazy, Admiral. A stream of coded messages going out from the Japanese to their Fleet being copied by us, decrypted to the degree you could, and then re-encrypted and sent out to US units.”

“Our system was pretty good,” said Mac, as I was trying to catch Peter’s eye and get the tab so we could take Willow’s moveable feast on the road home. I had dozens of napkins in front of me, all covered with cryptic pen strokes. “We called our machine code system the ECM- literally the Electric Coding Machine. As far as we could tell, it was unbreakable.”

“That is a useful thing in a code system,” I said. “When we found out the Walker assholes had been feeding the Soviets our codes for years, and that the machines themselves had been compromised by the North Koreans and Vietnamese, we realize how badly we were screwed.”

(Traitor John Walker)

“It is just good that we did not have to go to war with the Russians. But John Walker started supplying code material to them in 1967, and there is evidence that the Pueblo incident was a result of them wanting the machine enciphering equipment to run the keying material. The North Koreans were happy to help.”

“Everyone is upset about Bradley Manning and the Wiki-leaks thing, but Walker compromised millions of naval messages.”

“Yep,” said Mac, looking a little wistfully at the remains of him Virgin Mary. “And some good people died and many bad people didn’t because of those traitors. Communications security is how you save lives and win wars.”

Eventually, I got home and thought I might swim, and placed the stack of napkins next to the computer to try to work my own style of decryption in the morning. I was about to head down to the pool before Joanna the Polish Lifeguard locked up for the night when my pal the attorney called me up with a question. He was still at the office, on San Diego time.

“I have been reading about your conversations, and you know I have a legal mind. So, I was wondering what our Morse code operators actually copied down when listening on their intercept radios? It just occurred to me that Japanese is an ideograph language, so instead of words, even in plain text, they would have to have a series of cipher groups to stand for individual ideographs.”

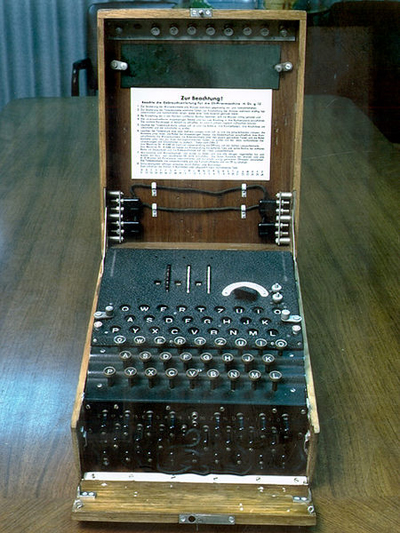

(Enigma Code Machine. Courtesy National Cryptologiic Museum)

“I don’t know,” I said. “I am much more familiar with the attacks on the German Enigma machines and the algorithms based on machine encryption. I am a liberal arts guy, but my understanding of that process is that when the rotors were set to the daily key setting, the operator would type in words in plain text and the machine would scramble it up into hundreds of thousands of variations. It would arrive at the distant end and be processed by a machine with the same rotor settings and come out in the original text.”

My attorney was not satisfied. “So did the COMINT operators copy something like would look like a string?

He rattled off a string of numbers as an example: “59442 break 66999 break 30522 break 99911 00456. That would produce an ideograph cipher-group that meant “Proceed full speed Point A”?”

“I don’t know,” I said. I will have to ask Mac.” I made a note to call him on Sunday. The Attorney has a reason to take this seriously. He had spent a year in Vietnam, right on the Cambodian Border, and walked into a Soviet COMINT site that had been located on one of the islands next to Vietnamese waters, eavesdropping on US battlefield communications.

The North Korean capture of Pueblo and the treasonous Walker disclosures ensured that the got great information.

By Sunday, and I was already depressed with the prospect of starting another working week. The pool had been unusually chilly when I swam, and the clouds had gathered in the afternoon and even this early in August there was the hint of the Fall to come.

I realized I was going to have to start planning shortly for an exercise activity that did not include the Big Pink pool.

To get my mind off the gloom of Black Sunday, I called up Mac at his apartment at the Madison where he lives. He was catching up on correspondence anyway and happy to talk. After some pleasantries, and making a tentative date for our next trip to Willow, I tried to paraphrase the attorney’s question.

“So, were there actually three steps in the decryption process of the JN-25 Naval Code. First to copy it accurately, then break the numerical codes that stood for Japanese ideographs, then to translate those ideographs into English?”

Mac hesitated briefly. “I’m not qualified to give a complete answer, Vic. I was neither a cryptologist nor a linguist. I was a Deck Officer with the basic investigations course. But here is how it worked in principle in the basement of Building One. Our intercept operators copied JN-25 five-digit code groups, as your friend guessed.”

There a pause on the line as Mac recalled. “These were not actual code groups, but were five digit groups taken from the code dictionary of 40,000 to 50,000 groups. Then, to encipher the message, the Japanese communications clerk would go to an Additive Table of random five digit groups that were added to the basic code group, with no carrying to the adjacent digit.”

“Then, to decipher the text, the receiving clerk would take the incoming encrypted message and go to the same table and subtract the additives to expose the clear text of the message, which can then be read from the code groups in the code dictionary.

“That doesn’t sound so hard,” I said.

“That was a very simplistic description of what the Japanese operators had to do, Mac snorted. “When we got the five-digit groups of the message through the intercept operators, the processing unit where I worked began to attack it. Our first task was to determine the additive numbers that were used and subtract them from the transmitted text. We called that step “stripping the additives,” and it got us to the basic code group. Then we would apply cryptographic skills to determine the possible meaning of each code group, one by painful one. Over time, with luck, some good guesses, and maybe an occasional crypto error by a Japanese clerk, the linguists could begin to recover the meaning of each individual code group.

“After months of effort, we could begin to read fragments of messages, and then things became easier. Greater volume of traffic, a few more operator errors, and greater familiarity with the system all contributed toward being able to read messages in greater detail. Of course, then the Japanese would change the additive tables, and we’d have to start all over again. The one thing that made all the difference was that the basic code group dictionary wasn’t changed during the entire war.”

I thought about that for a moment. “So when Jasper Holmes thought up his little plan to make the Japanese tell us the point of attack in their last major offensive, there was a missing code group for Midway island?”

Mac nodded. “Yep. Washington was convinced that the Japanese were going to land at Dutch Harbor in Alaska. Jasper thought the communications activity that suggested a northern attack was a ruse, and that the main battle force would try to take Midway. So, he convinced Rochefort and Eddie Layton to send a message via the secure underwater cable get the naval station on the island to broadcast that they had problems with their water evaporators.”

“Which was then copied by the Japanese, who reported the five digit code group of the place of attack had water problems.”

“Correct. It happened right by my desk in The Dungeon. Then all Eddie Layton had to do was convince Nimitz to gamble everything he had on the chance that Jasper was right.”

“What a story,” I said, looking at the increasingly cloudy sky.

(Japanese heavy cruiser of the Mogame Class on fire after attack by planes of Task Force 16, 6 June, 1942).

Mac cleared his throat. He quit smoking years and years ago, but he enjoyed his Lucky Strikes during the war. “I am not a linguist or a cryppie, so I cannot give you a more technical description of the process, and all the persons I worked with during WWII who could do so are six feet under. Someone at NSA might be able to do so, but you’d probably have to be cleared into his domain before he’d tell you, and then he might have to shoot you afterward. The Fort is kinda funny about such things, you know.”

I thought about the Walkers, and a war that was won, and one that was lost, and thanked Mac for his time. He may have told the story about Jasper Holmes a thousand times, but I will never lose my amazement for it.

“Next time at Willow we need to talk about how things changed after Midway at the Combat Intelligence Unit.”

“OK,” said Mac. “I’ll tell you how it worked at the Joint Intelligence Center, Pacific Ocean Area when we went on the offensive.”

“Cool,” I said.

Copyright 2017 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com