Iron Bottom Sound

The struggle for Guadalacanal was deadly and desperate- running gun battles in a narrow strait; Marines ashore, in contact with Imperial Japanese forces struggling over Henderson Field, the major strategic position on the island. RDML Sam Cox, commander of the Naval History and Heritage Command, visited the late Paul Allen’s unique exploration ship R/V Petrel as it conducted a survey of Iron Bottom Sound in search of two US Navy aircraft carriers, not seen in 75 years. This is his account.- Ed).

“The loss of WASP left HORNET as the only operational aircraft carrier in the U.S. Pacific Fleet for over a month, until a repaired ENTERPRISE arrived just in time to face four Japanese carriers (two fleet carriers, one medium carrier and one light carrier) in the Battle of Santa Cruz on 26 October 1942 during which ENTERPRISE was damaged again and HORNET was lost. The absence of NORTH CAROLINA and O’BRIEN (which had been upgraded with additional anti-aircraft capability) from HORNET’s escort screen was a significant factor in the number of Japanese aircraft that were able to penetrate the HORNET Task Force’s anti-aircraft defenses and inflict mortal damage on the HORNET. Although the damaged ENTERPRISE remained in the area, her significantly impaired capability gave the Japanese a window of opportunity to attempt to reinforce and resupply their troops on Guadalcanal, setting the stage for the costly night surface battles off Guadalcanal on 13,14, and 15 November 1942.

PETREL has a very sophisticated geospatial display capability. Paul Mayer had amassed every bit of positional data from every ship operating in the vicinity of the WASP at the time she was hit and the time she sank, which was displayed on the big screen. The first thing that was apparent was the positions were quite literally “all over the map.” My first thought was to comment that I had taken celestial navigation and it was a real (expletive,) and nobody was shooting at me while trying to do a sight form. Instead I came up with something more mundane about the challenges of open-ocean navigation in the days before GPS, or even Loran and Omega. Nevertheless, there was a general clump and one significant outlier. The outlier happened to be the position recorded by the navigator of the LANDSDOWNE, the ship that had actually scuttled the WASP, about 25 NM from the rest of the positions.

WASP’s navigator, who had been rescued by the LANDSDOWNE and was aboard LANDSDOWNE when she sank the WASP, recorded a position for where the WASP went down about 20 NM different from LANDSDOWNE’s navigator, which was somewhat perplexing. I recommended going with the WASP’s navigator’s position as it was likely he had more experience, plus it was basically the centroid of mass for the other recorded positions.

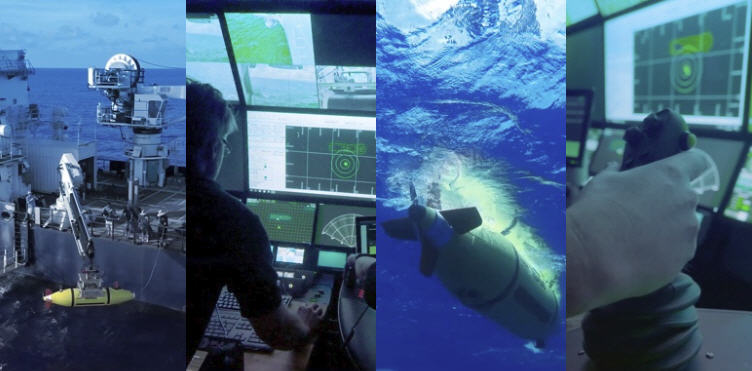

On the first attempt to send the AUV down to search, it decided to be a bit too autonomous and spontaneously aborted after a few minutes for reasons that were a bit of a mystery to the technicians. The second attempt also aborted after a few hours (a normal mission for the AUV would be about 18 hours to search roughly 40 square miles.) By contrast, once the AUV was recovered, exploiting that data only took about ten minutes to search the area on computer. By this time, the weather that was supposed to be getting better had gotten worse, and 15 foot swells made Zodiac operations unsafe. Finally, on 5 January, the AUV got in a full search, and located a debris field that stood out quite clearly against what was essentially a flat, featureless mud desert, 14,000 feet down. Since the wind was recorded as coming from the southeast, it was assumed that the WASP would have drifted to the northwest, and the next search was programmed accordingly, which resulted in a little more debris, but no ship. The next two attempts, postulating even more northwesterly drift, also came up as a zonk.

After four attempts, with nothing to show except some photos of spectacular sunsets and blurry pictures of Oceanic Whitetip Sharks (the species of INDIANAPOLIS’ nightmare,) one of the crew developed acute abdominal pain, which rightly led PETREL to make best speed (12 Knots) for the 30 hour return transit to Honiara for medical attention beyond that which could be provided by PETREL’s clinic. While waiting for the prognosis from the hospital ashore (which turned out well,) Robert Kraft asked if there were any wrecks in Iron Bottom Sound I would like to take a look at with the remotely-operated vehicle (ROV.) On a previous expedition, OCTOPUS had mapped out over 40 wrecks or potential wrecks in Iron Bottom Sound, some of which had first been located and explored by Bob Ballard on his expedition in 1991-92. I asked to see the destroyer LAFFEY (DD-459,) even though it was one previously located by Ballard, and the PETREL’s team obliged.

The reason I wanted to see LAFFEY was because a painting of her is on my standard NHHC briefing cover slide and another print hangs on the bulkhead behind my chair in the command conference room. The painting depicts LAFFEY in a close-quarters duel with the Japanese battleship HIEI. During the pre-dawn hours of 13 November 1942, LAFFEY was second in a line of 13 U.S. ships (five cruisers and eight destroyers) that plowed head-on into a roughly circular formation of two Japanese battleships, one light cruiser and 11 destroyers. The result was akin to a multi-car freeway pile-up in the fog that quickly degenerated into a hellacious no-quarter free-for-all.

Naval Historian RADM Samuel Eliot Morison described it as being like “minnows in a bucket.” A survivor described it as being like “a barroom brawl after the lights had been shot out.” The mission was to prevent the Japanese battleships from bombarding Henderson Field, which Captain Young on SAN FRANCISCO assessed as “suicide,” with which RADM Callaghan agreed, but said they had no choice. Young’s assessment was correct.

At one point early in the melee, LAFFEY passed directly ahead of battleship HIEI’s on-rushing bow emerging from a smoke screen, with a CPA (closest point of approach) of 20 feet. LAFFEY sprayed HIEI with every weapon she had, including the side-arms of officers on the bridge. LAFFEY pumped numerous 5-inch shells into HIEI described as “instantaneous impact,” most of which bounced off HIEI’s think armor plate.

Nevertheless, LAFFEY’s 1.1” and 20mm anti-aircraft guns fired rounds into HIEI’s bridge, wounding Rear Admiral Abe and HIEI’s captain, killing Abe’s Chief of Staff and other officers on the bridge. After the battle, Abe remembered nothing of what happened afterwards, and his ability to command and control the battle had been gravely impaired. In addition, LAFFEY’s shells caused HIEI’s pagoda-like superstructure to catch fire (described as “a burning high-rise apartment building” steaming through the battle) which then drew fire from numerous U.S. warships. LAFFEY also fired torpedoes at HIEI but at too close a range for them to arm.

As LAFFEY drew away from HIEI, she came under concentrated fire from three Japanese destroyers and the battleship KIRISHIMA. Hit by several 14” battleship shells and numerous smaller caliber rounds from the destroyers, LAFFEY lost speed before her stern was blown off by a torpedo from another Japanese destroyer. Shortly after LAFFEY’s skipper, LCDR William E. Hank, gave the order to abandon ship, a massive explosion killed him and many others. Chunks of the ship rained down on the destroyer O’BANNON (DD-450,) which otherwise went through the thick of the battle miraculously without any casualties. LAFFEY suffered 57 killed and 114 wounded, and Hank would be awarded a second Navy Cross, this one posthumously, and LAFFEY was awarded a posthumous Presidential Unit Citation.

As bad as the battle was for LAFFEY, she didn’t get the worst of it. Three other destroyers were sunk; CUSHING (72 killed,) BARTON (165 killed) and MONSSEN (145 killed.) The light cruiser ATLANTA was lost with 170 killed, including Rear Admiral Norman Scott (who had survived the sinking of the destroyer JACOB JONES (DD-61) in WWI) and who was killed by “friendly fire” from SAN FRANCISCO in the chaos. Scott would be awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor. SAN FRANCISCO survived, with 86 dead, plus 24 killed the day before when a crippled Japanese torpedo bomber deliberately flew into the anti-aircraft guns on SAN FRANCISCO that had inflicted the mortal damage to the bomber. SAN FRANCISCO in turn would hit HIEI’s in a critical location, knocking out her steering, as the two ships steaming on opposite courses fired broadsides into each other at a near point-blank range of just over a nautical mile. Only the fact that HIEI, having been caught by surprise by the presence of the U.S. force, was still firing mostly shore bombardment rounds and incendiaries likely saved SAN FRANCISCO, but not Callaghan or Young.

The next morning, the gravely damaged light cruiser JUNEAU was torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-26 and blew up, killing all but about 100 or so of her crew, of whom all but ten died over the course of ten days in the water due to exposure, salt-ingestion, and shark attack. All five Sullivan brothers were lost on JUNEAU. Including the JUNEAU, 1,439 U.S. Sailors died in this battle, making 13 November 1942 the bloodiest battle at sea in U.S. naval history. Fifty-seven U.S. Naval Academy graduates died in this one battle alone.

As the ROV reached the seabed and approached the wreck of the LAFFEY, it was once again a deeply emotional experience, knowing how many men had gone down with this ship in such a desperate battle. The damage to the ship was appalling. The descriptions in various accounts paled compared to the reality of seeing it. The bow area had taken at least one major caliber shell hit, and was crunched so the hull number could not be seen in the crumpled folds. The entire superstructure was perforated like the bridge wing at the SAN FRANCISCO memorial, yet through the zoom lens the engine-order-telegraph on the bridge could plainly be seen, intact. The two forward 5-inch turrets looked like they had been blasted open from the inside, the number two turret trained aft as far as it would go. Both funnels had been blasted off and a huge gaping hole led to the engineering spaces. Reports said the stern had been blown off aft of the aftermost turret (No. 4.) The stern was indeed missing, so no name could be seen, but everything after where the aft funnel should have been was completely mangled.

As the ROV carefully inched its way along each side of the ship, uncertainty began to mount among PETREL’s crew as to whether this wreck could be confirmed as LAFFEY. There were enough features still visible that I could identify it as a Benson-class destroyer. I asked the ROV operator to take a close look at the forward 5” gun director, as the BARTON (lost in the same battle) had a newer type fire control radar, and this one matched LAFFEY, so I was convinced, although others were still suffering lingering doubt. As the ROV was about to end to search, one of the operators spotted some sort of rectangle on the bulkhead at the quarterdeck. Using the powerful zoom optics of the ROV, the rectangle proved to be the builder’s plaque, and “U.S.S. Laffey” could be seen through the marine growth. The sight of this ship, which had gone down fighting so heroically, evoked intense emotions in me that I can only liken to a religious experience. The ship herself was the only marker these men had.

After the doctors ashore worked their magic, it wasn’t long before PETREL was back underway heading southeasterly from Guadalcanal to resume the search, quickly rejoined by the oceanic whitetips, in the five-to-six foot range, whether the same or different group as before there was no way of knowing.

Copyright 2019 Sam Cox

www.vicsocotra.com