Memorial Day: May They Rest in Peace

General Order

No. 11

Headquarters, Grand Army of the Republic

Washington, D.C., May 5, 1868

I. The 30th day of May, 1868, is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet churchyard in the land. In this observance no form or ceremony is prescribed, but posts and comrades will in their own way arrange such fitting services and testimonials of respect as circumstances may permit.

We are organized, comrades, as our regulations tell us, for the purpose, among other things, “of preserving and strengthening those kind and fraternal feelings which have bound together the soldiers, sailors, and marines who united to suppress the late rebellion.” What can aid more to assure this result than by cherishing tenderly the memory of our heroic dead, who made their breasts a barricade between our country and its foes? Their soldier lives were the reveille of freedom to a race in chains, and their death a tattoo of rebellious tyranny in arms.

We should guard their graves with sacred vigilance. All that the consecrated wealth and taste of the Nation can add to their adornment and security is but a fitting tribute to the memory of her slain defenders. Let no wanton foot tread rudely on such hallowed grounds. Let pleasant paths invite the coming and going of reverent visitors and fond mourners. Let no vandalism of avarice or neglect, no ravages of time, testify to the present or to the coming generations that we have forgotten, as a people, the cost of free and undivided republic.

If other eyes grow dull and other hands slack, and other hearts cold in the solemn trust, ours shall keep it well as long as the light and warmth of life remain in us.

Let us, then, at the time appointed, gather around their sacred remains and garland the passionless mounds above them with choicest flowers of springtime; let us raise above them the dear old flag they saved from dishonor; let us in this solemn presence renew our pledges to aid and assist those whom they have left among us as sacred charges upon the Nation’s gratitude,–the soldier’s and sailor’s widow and orphan.

II. It is the purpose of the Commander-in-Chief to inaugurate this observance with the hope it will be kept up from year to year, while a survivor of the war remains to honor the memory of his departed comrades. He earnestly desires the public press to call attention to this Order, and lend its friendly aid in bringing it to the notice of comrades in all parts of the country in time for simultaneous compliance therewith.

III. Department commanders will use every effort to make this order effective.

By command of:

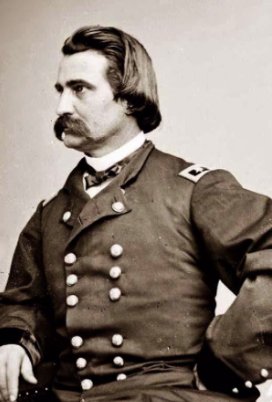

JOHN A. LOGAN,

Commander-in-Chief.

N. P. CHIPMAN,

Adjutant-General.

Forgotten Memory

Whenever we hear the phrase – Memorial Day – our thoughts are drawn to either the more recent wars – Afghanistan, Iraq, perhaps Vietnam, or those with large numbers – World War II, World War I, perhaps even the Civil War.

But the US has fought in some 75 to 80 wars or crises (depending on how you count them) in which we have suffered combat losses. Many, most, are forgotten. We have even used the phrase “the Forgotten War” to note one that cost nearly 37,000 US lives – Korea. Yet, while many of these wars were “unimportant,” and “low intensity,” and are now forgotten, to the Soldiers and Sailors and Airmen and Marines who were killed (and to their families, and to their buddies who were there, and often wounded), the distinction between skirmishes and “low intensity conflict” (to use the modern phrase) on the one hand, and unlimited war on the other, is a distinction that matters only to those sitting around a distant table in Washington. As the saying goes: low intensity is when they’re shooting at somebody else, high intensity is when they’re shooting at you.

And, while we can argue about the propriety of this or that engagement, or the legitimacy of this or that war, to those on the ships, in the planes, on the ground, who had been ordered to be there, those arguments – again, fade rapidly and are replaced with concerns about completing the assigned mission and getting “back to the ship” in one piece.

So, while it’s easy in hind-sight to look at the long list of wars and skirmishes and wave them off as unimportant, of no consequence, they were of great consequence to those who fought and died in them. Those who fought and died, whether in the Revolution, the Civil War or World War II, or the War against the Barbary Pirates, the Sumatran Expedition, or the Korean Expedition of 1871 – they all served, they all gave their lives for our nation, they all deserve to me remembered.

Consider, for example, the Second Opium War.

The Opium Wars, which were really a series of battles (small and large) fought between the Chinese Emperor (the Qing Dynasty) and the British (and occasionally other powers when their interests matched that of Great Britain’s) was about control of trade into and out of Chinese ports, and the sale of opium in China. Opium usage was banned in China, but much of the rest of the world viewed it as legal. The British East India Company began selling large amounts of opium, with the support of the Royal Navy, to offset the trade imbalance that had developed between England and China over the first half of the 19th Century. While there was a significant social stigma in Europe to the use of opium and many leading figures (such as William Gladstone, later PM of England) opposed the trade, the opium trade grew rapidly in size and importance.

The First Opium War ran from 1839 to 1842 and the US was not involved militarily. US merchants were aware and watched the proceedings with great interest, as they, while not involved in the opium trade, did want access to Chinese ports, and in 1844 the US concluded a trade agreement with the Qing dynasty that granted the US most favored nation trading status.

From 1842 to 1855 things, as they say, festered. The British wanted to extend trading rights in East Asia and China specifically, and a treaty violation in 1856 (the extent of the violation is pretty much dependent on which side of the quarrel you sit on) led to four more years of skirmishes between the British and the Chinese, with added support from several other European countries, particularly the French. As with the first Opium War, British technological advantages made the result nearly a foregone conclusion, but still the war dragged on for 4 years.

The US, which was already trading widely in China, claimed neutrality. In late October 1856, a leading American businessman, a certain Mr. Sturgis of the Russell & Co. trading house, persuaded Commodore James Armstrong, commanding the US Navy’s East India Squadron, to withdraw from Canton the few American citizens in the city, as well as the party of Marines and Sailors (150 total men) put ashore to protect them.

When, on November 15th a small boat from USS Portsmouth went up river as part of this effort, Chinese soldiers in the Barrier Forts fired on them. Enter Dr. Peter Parker, a physician who had been in Canton on and off for more than 20 years. Parker had helped Caleb Cushing negotiate the first treaty between the US and China in 1844 and had returned at President Pierce’s request to renegotiate the treaty (as was stipulated in the first treaty). Parker wrote to the head of British interests, Sir John Bowring, and stressed US neutrality.

But Commodore Armstrong considered the incident an insult to the US and was “determined to punish the national affront.” On Sunday afternoon, November 16th, USS Portsmouth (20 guns) and USS Levant (22 guns) proceeded up the river under the command of Commodore Andrew H. Foote, and landed (despite some navigation troubles), 287 Marines and Naval Infantry, and stormed the Barrier Forts. In three days of fighting they captured the 4 forts, suffering some 42 casualties. At least 5 Americans were killed and 37 were wounded.

Tensions eased off a bit, but kept rising and falling for the next three years as the British kept pressing their demands. In 1859 at the Second battle of the Taku forts, a series of forts along the Hai River (referred to at the time as the Pei Ho (The Pei River or White River), the river that runs from Beijing to the Bahai Gulf), Commodore Josiah Tattnall supported the Royal Navy operations, to include a landing, against the forts. The entire campaign was rather complicated and involved a good deal of posturing and maneuvering. In addition, Tattnall, on USS Powhatan, found his ship too large to navigate the river and accordingly chartered a small steamer, ToeyWan, Between those men on ToeyWan and those that simply made their way aboard several of the Royal Navy and French Navy gunboats, some 200 US Sailors and Marines took part in the attack.

The attack was a bit of a mess – a “disaster” as Jack Beeching calls it in his work “The Chinese Opium Wars” – the tide was falling and as the men tried to wade ashore they became mired in river mud, under the guns of the Taku forts. Of the total of 1100 British, French and American troops who tried to land, 434 were killed or wounded. Fortunately, only 1 American was killed and 1 wounded, and miraculously, the Chinese agreed that the US was still acting as a neutral.

The US participation in the Second Opium War over the course of the war was of little real consequence; it really was a British effort from start to finish. But for the Sailors and Marines who fought in it, for the 12 men who died in it, it was quite as real as any other war, and their sacrifice was as real.

Today, the war is all but forgotten in the United States, and their names and even the names of the senior officers, have faded. Josiah Tattnall, who went on to serve in the Confederate Navy during the Civil War, had two ships named after him in the 20th Century, DDG-19, launched in 1961 and Decommissioned in 1991, and earlier DD-125, launched in 1918 and decommissioned in 1946. Andrew Foote served with distinction with General Grant and his support of the Army was critical in the battles of Fort Henry, Fort Donelson and Island No. 10. He was the key figure in developing the tactics that allowed the US Navy to gain control of the Mississippi and Tennessee Rivers, and three ships – TB-3, DD-169 and DD-511 – were named after him.

Overall, the US participation in the Opium Wars was of little real consequence; it really was a British effort from start to finish. But for the Sailors and Marines who fought in it, for the 12 men who died in it, it was quite as real as any other war, and their sacrifice was as real. When we remember those who died, it is easiest, when we remember anyone at all, to remember those who died in major battles and major wars. But, perhaps, we should take a little time and recall the Sailors, Soldiers, Marines, and Airmen whose names we have forgotten, whose battles we have forgotten, even whose wars we have forgotten. Say a prayer for them too, this Memorial Day.

May they all Rest In Peace.