Arch Cunningham’s Lost Cause

OK- I found the concluding line to the couplet that ends Uncle Pat’s obituary. I mentioned that it was more work than usual, but after some false starts, I was eventually able to find the publication in which it originally appeared. It was a curious thing, one I should have focused on at the front end, but I have never been interested in old Veteran’s magazines, including the organizations I actually belong to.

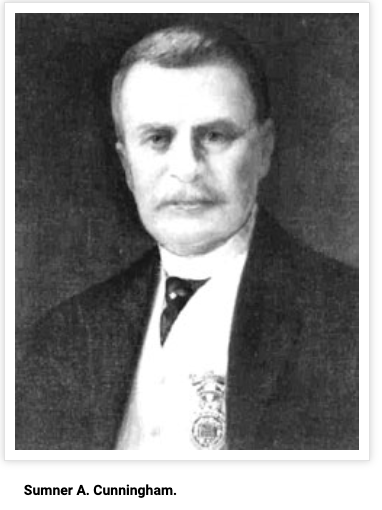

Uncle Pat’s notice appears in the July 1921 issue of The Confederate Veteran, a publication I never would have stumbled across had it not been for mention of Sumner Archibald Cunningham in the obituary, a tribute to a pal who obviously meant a great deal to Pat.

Since I had run out of other ideas to query, I searched on Cunningham’s name to see if there was a reference that would assist my search. What I found knocked me out. You know me- I feign perfect knowledge all the time, but this was all new. Sumner A. Cunningham, dead since 1915, turned out to be a major player in today’s fight about the legacy of the Confederacy and the scourge of the institution of slavery in these United States. I think he would be a little let down with what is going on today after all the effort he put in to try to tell the story the way he wanted. He was there, and to my mind, should at least get to tell his side of things.

I was stunned at what he did from his base in Nashville. It may be some modern myth-buster’s insertion of opinion into fact, but there is enough left to paint Arch as either a blatant propagandist or valiant defender of an idyllic South. I had never heard of him, and it is safe to say that few people so adamant against his ideas around today would have. Even the shrillest opponent of events played out a century ago would have a difficult time picking him out, even if they are ripping down statues of other people they don’t know. Sumner knew his version and he sold it with incredible success.

I was still in a mess when the mail came. I am on high alert, since a check to pay for the truck I sold is supposed to show up at some point. Accordingly, I trooped up to the county road with mild anxiety to check the box. There was some of the usual trash, letters requesting funding for components of the overwhelming political circus and a couple from causes I used to support when I was still working.

After I trudged back down to the house, hung up my cane and got planted back in my geezer chair, I glanced at them. One fat envelope was from the nice folks at the American Battlefield Preservation Society.

I like them. I contributed to their fund to save property from development at Manassas on the famous Bull Run. They have wisely changed their name from something that mentioned our Civil War, since you and I know how our current woke sensibility cannot abide history until we have a chance to re-write it to reflect today’s evolved sensibilities.

I have no particular interest or passion about manufacturing new narratives about things that happened long ago. In researching the family tree, I have often thought about the failure of the potato crop in Ireland. It was bad. Starvation forced part of my family to cross the waves in 1847, one of the acute years. That discouraging time starved a million people and forced another million to join Pat’s family in a diaspora across the Northern Passage of the Atlantic. That amounted to a decline in the Irish population of nearly a quarter, and in many cases the imposition of indentured servitude on those who had no resources to fund migration. I don’t hear a lot about that, or the other tough luck situations that brought diverse peoples to these shores.

I opened the thick envelope to see what the Preservationists were up to. I should have been surprised by what I found, but I blush to admit that these days I find nothing is beyond belief. This particular appeal was to purchase some acreage in Raymond, Mississippi and near Vicksburg, Tennessee. Those places got my attention.

A few years ago, I trespassed with a pal on some private land about three miles outside Raymond. We successfully found the scene of Uncle Pat’s combat story of saving the body of his Colonel, Randall McGavock. It is a patch of pasture just above a tree line on a small creek, just as he described it. The other property the Society is looking to save is along the old trench lines of the Vicksburg siege. That is where Grandpa James spent time as the regimental teamster for an Ohio infantry unit.

Retired or not, I couldn’t avoid contributing. My goal is only to see if the properties could be left alone, not littered with monuments undoubtedly offensive to changing times. The Society normally puts up only a modest marker and otherwise leaves the land as it was when earnest and frightened people died on it.

So, as I filled out a check, I was thinking about the guy I just found out about, Mr. Cunningham, since he was there too, not far from Uncle Pat.

I don’t know if some of the stories about Arch are true. One source claimed him to be particularly adept at determining alternate places of duty when it looked like the 41st Tennessee was going to be engaged in a big fight. He would return after the fighting was done without court marshal, according to some historians. He was promoted anyway, something I find unusual from a military perspective. Cowards are normally ridiculed and held back in the ranks. Whatever the actual case might be, he made Sergeant Major and it seems at least agreed that he was an agreeable man.

I began to understand why he was important to Pat as I scanned records, though his larger impact of society was still something I did not fully appreciate. Arch Cunningham had been born to a family that owned other human beings. He did the things growing up you would expect of that sort of gentry in Middle Tennessee. He signed up for duty in a local militia in October of 1861, which later was absorbed into the state’s 41st Infantry.

That was about the same time my Uncle and Granddad heard the call from the opposing bugles. Arch was on garrison duty, but got captured after the fight at Ft. Donelson, just like my Uncle. They spent an uncomfortable winter up north before being exchanged for Union prisoners and returned to their units in 1862.

(Arch Cunningham as a young soldier)

Regardless of the modern aspersions cast on his military virtue, Arch was reportedly a hero at Raymond like Uncle Pat, and did his time. Like my grandfather, he called it quits in 1864. And that was the beginning of the idea that made him famous.

His work history after the war consisted of a variety of publishing jobs, mostly in the newspaper trade. Biographers said his growing interest in the veteran community was part of a larger cause. The passion of his life became rectifying the legacy of a South that he believed had been dishonored in the crushing defeat and the occupation by Federal troops.

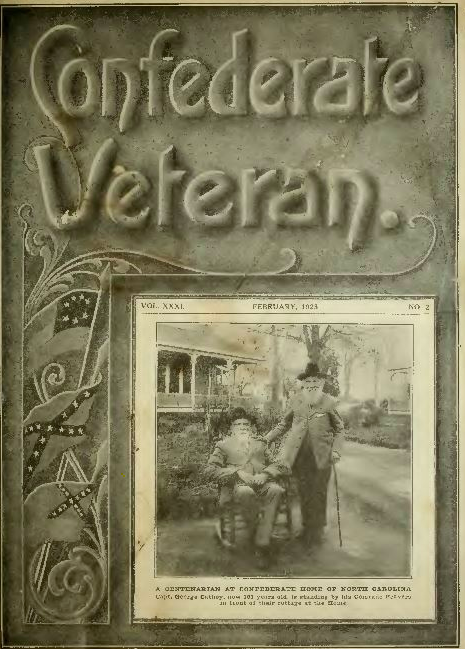

The indomitable spirit that consumed him was the presentation of the Confederate heritage in unmistakable and positive terms. Critics termed him a man of “no more than average intellect,” but his drive and energy were unmistakable. After years bouncing around the press, in 1893, he founded a monthly newsletter to espouse his growing sensitivity. He called it “The Confederate Veteran,” a publication he zealously produced for the last two decades of his life.

Based on the enthusiasm of the large Southern veteran community and others who longed for the antebellum righteousness of their homeland, he became a spokesman for what people today call “The Lost Cause.”

It is an essential component of Southern historiography in the post Reconstruction era. In fact, it was so successful that it became an integral part of history taught across America, and even in the schools of the victorious North as part of a spirit of reconciliation. Our Boomer generation experienced it in our day and it included the notion of a valiant South crushed by a mercantile-based Union for the crime of exercising their alleged right to secede. Up North, we were pro-Union and against slavery, but recognized there was another narrative.

Arch’s narrative was based on the Constitution, or at least his interpretation of it. The 10th Amendment stated boldly that powers not specifically allocated to the Federal Government were reserved to the states, or the people. Secession was a state’s rights issue, said the Lost Cause.

It was a story of victim-hood. Beginning in 1921, the year Uncle Pat passed, the Confederate Veteran magazine sponsored scholarships and even evolved into a syndicated radio broadcast. The message stayed strong about a genteel society populated by gracious people who supported the wellbeing of their chattel slaves.

The Cunningham Lost Cause message inspired some of the early works on the silver screen, such as D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation,” shown by President Wilson in the White House, and later the glorious “Gone With the Wind.” That film produced the first Oscar Hollywood awarded to a woman of color, Ms Hattie McDaniels, and presented the overarching family image that Arch had carried to his grave.

William Faulkner was a pretty good southern writer, I hear. He summed the Lost Cause spirit up nicely about Gettysburg:

“It’s all now you see…. For every southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid and ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened to break out and Pickett himself … looking up the hill waiting for Longstreet to give the word and it’s all in the balance, it hasn’t happened yet, it hasn’t even begun yet, it not only hasn’t begun yet but there is still time for it not to begin against that position and … yet it’s going to begin, we all know that, we have come too far with too much at stake and that moment doesn’t need even a fourteen-year-old boy to think This time. Maybe this time.”

The Nashville-based Confederate Veteran stood tall for the Cause and blew reveille for meetings of the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC). It published information on reunions, reenactments, and monument raisings, and filled its columns with reminiscences from Southern enlisted men about the nation that was lost.

Arch even sponsored the memorable refrain of “Dixie” as a musical memorial to a time when he claimed there was Christian honesty in the land, and the freedom for people to be what they desired, not to be forced to comply to the desires of central power in Washington.

Uncle Pat knew him as Arch’s Southern star was rising. We can hear echoes of that in the fight about history today. In fact, the disturbances in America’s streets today are billed as riots against Sumner Cunningham’s ideas. And against my Uncle, too, when I think about it.

I don’t know what my Ohio Granddad thought about it. Communications in the family were not that good after the cause was lost.

Copyright 2020 Vic Socotra

http://www.vicsocotra.com