The Rotunda

Author’s Note: This was a rough from 2005, a long time ago in modern terms. In that year, Minneapolis-Saint Paul was still a bustling modern city that had few immigrants beyond the ones who had come from Scandinavia. We don’t want to pick on any particular group, since these days the discussion spins off into something else. There is a minor story going around about how the vast expansion of Federal funding for social projects actually works. It involves a member of Congress, and the disbursement of what then would have been considered a vast expenditure of taxpayer dollars- around a half billion of them, parsed out to several non-profit groups that saw their budgets expand a hundredfold and were largely unaccountable for how it was spent. That is not exactly what happened to our home town of Detroit. That former great city will occupy the “D” category in the Alphabet Cities saga, but this note is about a single structure there. It was amazing in its time. Here is a short note about things that shaped lives.

– Vic

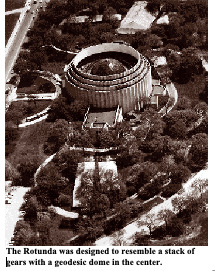

The building had its roots in the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, known as the Century of Progress Exposition, which opened in May of 1933 and attracted more than 40 million visitors over its two-year run. One of the major attractions at the fair was Ford Motor Company’s Rotunda, a structure built as a Ford showpiece for the 1934 Chicago World’s Fair. The building was designed by Albert Kahn, one of the premier architects who molded Detroit, Michigan as the “Paris of the Midwest,” a title that now seems ironic.

His design was industrial in theme. It included a central hall reminiscent of a huge gear made of steel and weatherproof papier-mâché. That portion of the structure was disassembled after the fair and brought back to Dearborn, Michigan, where it was reconstructed using more permanent materials. Designed to be the showcase of the auto industry, the Ford Rotunda was opened to the public on May 14, 1936.

The original steel framework was covered with Indiana limestone, forming a design representing a stack of gears, decreasing in size towards the top. Located on Schaefer Road, across from the Ford Company’s Administration building, the circular structure had an open courtyard 92 feet in diameter with a wing on either side.

Ford had decided to dismantle the building and move it to Dearborn as a tourist attraction. When reconstructed, the Rotunda was built out of limestone on the original framework. The Rotunda featured automotive exhibits and seasonal shows. A 1961 Ford news release was issued when we were ten years of age. It detailed one “summer spectacular” with the “Star of the show as the Gyron, a futuristic car that would run on two wheels, using a gyroscope for stabilization … ”

For generations of Detroiters the only place to be at Christmas time was the Rotunda. From 1936 to 1962, the gear-shaped Ford Rotunda attracted visitors from around the world. It was the fifth most popular tourist destination in the United States in the 1950s.

Huge murals on the walls depicted the manufacture of the Ford automobile. Exhibits were changed regularly, but Ford products always took center stage. One of our favorites was what surrounded the Rotunda. The grounds contained reproductions of 19 historic Roads of the World: the Appian Way from Italy, the Tokaido Road in Japan, the Grand Trunk Road in India, a Mayan road from the Yucatan, the Oregon Trail and a wooden plank section of Woodward Avenue, the grand first concrete road in America where I got my first speeding ticket only a few years later. It was in a Chrysler 440RT Charger, with my apologies to Mr. Ford and later my Dad.

Besides its own attractions, the Rotunda served as the gateway for tours of the Rouge Plant, which produced Mustangs after it had been the arsenal of Democracy against the Germans and Japanese. We mentioned the other American tourist hotspots. The Rotunda ranked behind only Niagara Falls, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, The Smithsonian Institution and the Lincoln Memorial as a national tourist destination. It was more popular than Yellowstone, Mount Vernon, the Washington Monument and the Statue of Liberty.

The building was closed to the public during World War II, and following the War underwent a massive remodeling. Dad had joined Ford as a clay stylist in 1948 when he relocated from Brooklyn with his bride Betty. In 1952, the courtyard was covered with an innovative 18,000 pound dome. The weight of a conventional dome would have come in at 320,000 pounds and would have crushed the structure. Ford management turned to R. Buckminster Fuller, who came up with the design, the first commercial application of his experimental geodesic dome.

That may have been the most futuristic component of the Kahn design, but the one that appealed to us was what encircled the Rotunda. It was an oval drive, composed of 21 segments. Each told the history of global road construction. They ranged from dirt roads signifying early civilization, through wooden, cobblestone, and brick streets, to the most modern concrete highways like Woodward, the first one poured in the USA. Ford’s oval illustrated innovation in the movement of people.

With Fuller’s dome, the Rotunda was “ultra-modern.” It reopened as part of Ford’s 50th anniversary celebration on June 16, 1953. A radioactive wand (the tip contained a small amount of radium), said to be symbolic of the arrival of industry at the threshold of the atomic age, turned on golden floodlights and lighted 50 huge birthday candles around the rim of the Rotunda. The wand bombarded a Geiger tube with 44,890,832 gamma ray impulses in 15 seconds. The final impulse (the number signified the number of vehicles produced by Ford since 1903) was said to trigger the electrical system.

With the Rotunda’s new design came a new lure for visitors: an annual Christmas display called the Christmas Fantasy, which first opened on Dec. 15, 1953. Nearly a half million visitors saw the Christmas show that first year. In 1954, Story Book Land came to life, with Hansel and Gretel, Little Boy Blue, Puss in Boots, Little Bo Peep and Humpty Dumpty animated by machines performing around a vast Santa Claus castle. In 1958, a 15,000-piece miniature circus highlighted the Fantasy. The hand-carved circus was the creation of Jean LeRoy, a famous former circus clown.

The preparations for the 1962 Christmas display were well under way when disaster struck on Nov. 9. While workers were applying tar to Fuller’s dome for weatherproofing. They kept it malleable with an infrared heater that inadvertently caught fire. Shortly after 1 p.m., an employee saw flames on the ceiling of the main floor, and gave the alarm. Workmen raced down from the roof as flames shot 50 feet high. The black smoke was visible for miles.

In less than an hour the Rotunda lay in ruins. All employees and display workers escaped injury, except for the engineer in charge of the building, who ran to the roof at the first alarm and suffered from smoke inhalation. The roof collapsed shortly after the fire started, and only a shouted warning to the firemen got them out of the building before the gear-like walls collapsed.

The ring road of transportation history is still there, though not a tourist attraction. Ford could have rebuilt it, but times were changing. The site is now home to a family service and learning center, a child-care center and the Michigan Technical Education Center. We preferred the Rotunda, but that is the way cities go these days, you know?

Copyright 2022 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com