Amending Prohibition

There is a fair amount of confused excitement out here in the Country. In fact, there is enough of it that Amanda, our watch-Attorney, was moved to get on the Chairman’s calendar to seek some relief. Apparently some of his Writer’s Section, attempting to bridge the wide gap in coverage, have been getting information from one of the broadcast signals not using the assigned talking points to frame the ‘news.’ The Chairman shrugged, and the matter was resolved by a prohibition on all media during any time it was interesting.

But confusion continued. Loma got a note from an old shipmate complaining about something he didn’t really understand. He had been retired from active service for several decades, and the matter brought to his attention was one purely in the public (and unfortunately legal) domain. He was told discussion of the issue was harmful, and hence prohibited.

That naturally led to a discussion of prohibition, which the group is generally opposed to it as a social mechanism.

The 18th Amendment naturally was a starting point. It began with a good idea that had roots in all sorts of good things that were discussed for a long time. Two hundred years ago a wave of religious revivalism swept the young United States. One of the virtues advertised was a thing called ‘temperance.’ There were other good ideas that ran their course through that same period, encompassing movements in favor of ‘perfectioning’ society. Abolition was one of them, so you can see there is a fair amount of history to these Amendment things.

An early adopter even then, the State of Massachusetts banned the sale of spirits in less than 15-gallon containers in 1838. Splash said he could be persuaded to join that sort of temperance movement, if he had a cart. The state legislature repealed it in 1840, though we are not completely sure why. It may have been an issue on transporting that much hooch on horseback, a practical matter of personal liability.

To the north in Maine, an actual state-wide prohibition law was passed in 1846 and it was followed by a stricter one five years later. Other states followed suit by 1861, when other Good and Bad ideas played out in the course of a massive Civil War.

Social activism continued to play out in matters of law and Constitution. Amending the latter document is derived from Article V in the latter document, a popular favorite here at Refuge Farm. Here is how that works: after Congress proposes an Amendment, the Archivist of the United States is charged with responsibility for administering the ratification process under the provisions of 1 US Code 106b. The Director of the Federal Register is immediately drawn in. The Archivist and the Director follow procedures and customs once held Secretary of State until 1950, the Administrator of General Services until 1985 and now the National Archives and Register Administration (NARA).

The Constitution provides that an amendment may be proposed either by the Congress with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate or by a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of the State legislatures. The latter has never been attempted, though talked about a lot.

Once over that first internal hurdle, Congress proposes the Amendment in the form of a Joint Resolution. Since the President does not have a constitutional role in the Amendment Process, the Joint Resolution does not go to the White House for signature or approval. The original document is forwarded directly to NARA’s Office of the Federal Register (OFR) for processing and publication. The OFR adds legislative history notes to the Joint Resolution and publishes it in slip-law format, which we would require Amanda to explain to us.

The OFR also assembles an information package for the States which includes formal “red-line” copies of the Joint Resolution, copies in slip law format, and the statutory procedure for ratification under 1 U.S.C. 106b.

The Archivist submits the proposed amendment to the States with a letter of notification to each Governor with informational material prepared by the OFR. The Governors then submit the amendment to their State legislatures, or the state may call for a convention, depending on Congressional specification. In past practice, some States have not waited for official notice before taking action since they are, in a way, entitled to do as they please.

When a State ratifies an Amendment, it sends the Archivist an original or certified copy of the State action, which is immediately conveyed to the Director of the Federal Register. The OFR examines ratification documents for legal sufficiency and an authenticating signature.

If the documents are found to be in good order, the Director acknowledges receipt and maintains custody. The OFR retains these documents until the Amendment is adopted or fails, with preservation the responsibility of the National Archives.

A proposed amendment becomes part of the Constitution as soon as it is ratified by three-fourths of the States (38 of 50 States). This certification is published in the Federal Register and U.S. Statutes at Large and serves as official notice to the Congress and to the Nation that the amendment process has been completed.

So, you can see there are several people standing around these things, watching carefully.

In the case of Prohibition, temperance societies were standing around as well. For decades. These organizations were a common fixture across the United States. As a sign of another parallel Good Idea for social order, women played a strong role. Alcohol was seen as a destructive force in marriage and family matters. In support of order, the Anti-Saloon League was established in 1893 to oppose disorder in drinking establishments. These were mushrooming in growing urban areas, and many considered saloons corrupt and ungodly. Factory owners supported the movement for safety reasons on the new ‘assembly lines,’ and to increase productivity in extended working hours.

A spark was necessary for this Good Idea. The violent global aberration of the War to End Wars provided one in 1914. The concept of “Emergency” to “Do something” is not new. This particular one is a matter of some complexity, and relevant to discussions of other matters today.

How could the matter become Law of the Land? There are two ways to get an Amendment adopted by Congress. The first step is putting the proposed Amendment to votes in the Senate and House. If approved by a 2/3rd margin in both chambers, it moves forward. That means, as of this moment with 50 states participating, 34 of them must agree. Tall order, but emergencies have their own urgency.

Congress can alternatively call for a National Convention on Constitutional matters, should 34 states request one. There is periodic discussion of that as a rational solution to the changes of technology and social custom that have evolved since the Founding, and pervasive fear that such a convention would range far beyond rational consideration. While 33 Amendments have been proposed, no Constitutional Convention has ever been convened.

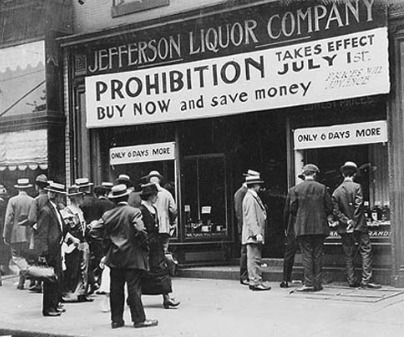

The 18th Amendment process to prohibit alcohol began as war clouds also loomed here at home. President Wilson supported regulations to improve factories churning out war materials for the conflict overseas. In order to rectify the nation-wide problem, the 18th Amendment was proposed to rid us of the curse of alcohol. Congress allowed a reasonable 7-year period for the process to unfold, but it was passed in only eleven months. The Amendment specified the prohibition on manufacture, sale and transportation of alcoholic beverages nation-wide.

It was ratified on January 16, 1919, as part of the U.S. Constitution.

That was just the start, though. As with many Constitutional issues, this one required amplification and clarification in U.S. Code, since many of the Good Idea’s provisions were unclear, regardless of their seeming universality.

For example, there was no definition of what an “intoxicating liquor” might be, or what penalties should be applied for violations of its prohibition.To clear those things up, the Volstead Act was introduced in the House of Representatives in 1919 to remedy unclarity. It was vetoed by President Wilson (or his wife Edith, that moment in Presidential history being unclear) largely on technical grounds, since it also covered wartime prohibition issues.

The Veto was overridden the same day in the House and the next day by the full Senate. The nation was presented with the new law enforcing the Amendment that would:

Prohibit intoxicating beverages such as liquor, beer and alcohol,

Regulate the manufacture, production, use, and sale of high-proof spirits for any purpose, other than beverage purposes,

Ensure an ample supply of alcohol for use in scientific research and for fuel, dye, and other lawful industries.

In sum, it directed there be “no manufacture, sale, barter, transport, import, export, delivery or possession of any intoxicating liquor except as authorized in this Act, which shall be liberally construed to prevent the use of intoxicating liquor as a beverage.”

That was deemed clear enough, and set the limit on beverages to be regulated as those containing half a percent of alcohol by volume. That limit effectively banned beer and wine, which took many by surprise, including some supporters of the original Good Idea.

There is no time this afternoon to consider some of the consequences of the Act, which would seem to impose the power of law prohibiting sacramental use of wine, but that is the problem with Good Ideas that contain assorted issues. In this case, Prohibition tended to increase illegal production, sale, import and delivery of the Prohibited Substance.

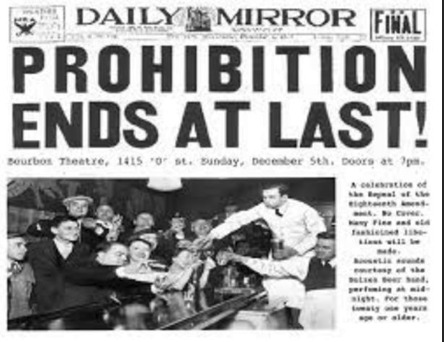

There was an accompanying increase in the number of now-illegal but highly profitable activities. These became so problematic in the decade the followed that the Amendment process was again commenced, with the introduction of the 21st Amendment that rumbled through the House, Senate and Statehouses of the then-48 States.

The 21st Amendment was ratified on December 5, 1933, ending that Good Idea. President Roosevelt reportedly celebrated with his favorite beverage, a dirty martini.

We bring that whole mess up in light of some of the stuff going on in Washington. Discussion now involves the matter of mass shootings, which we consider (unanimously) a Bad Thing. There was discussion of a new Amendment to be proposed, which some consider a Good Idea. One idea is simply to prohibit possession, manufacture, sale or distribution of firearms. There is a general feeling here that such an Amendment might forestall or at least minimize mass shootings.

We could even support it, if someone could propose the necessary legislation to support the confiscation of the 400 million such devices already in circulation. So you can see, based on previous experience, that no one wants to get into the Amendment process stipulated in our Constitution. We may instead get some new laws, which seem to violate the very simple provisions of the un-Amended Constitution.

Buck rose to enumerate some of them, but we asked him to sit down so we could go to lunch. We are opposed to violence unless stipulated by Congressional act. We are universally opposed to murder. We also believe that it is already clearly and unambiguously against existing law.

Rather than trying to get two thirds of members of Congress and two thirds of the States together to vote a new Amendment, we thought someone should consider enforcing the laws that already exist.

If that is too hard, that poses another issue, which is that we have created a nation that can no longer follow its own laws. If you have a Good Idea on how to fix that, we would naturally be interested in hearing it.

Copyright 2022 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com