Life & Island Times: Departure

Editor’s Note: Marlow is visited by the miracle of Sunday Morning just as we were. Salut!

-Vic

Author’s Note: In May, 60 years had passed since elementary school. Some old friends from those days reached out recently and memories flowed. This resulted.

-Marlow

Departure

Most of us didn’t want to be a product of our environment. We wanted our environment to be a product of us.

Years ago, we (I really mean me) in the 50s and early 60s had the Church. That was only a way of saying we had each other. We knights of Catholicism were head-breakers. We took our piece of the near-north side of town.

The neighborhood of Clintonville was an early bastion of the American Midwest’s temperance movement. So, there was no alcohol by the drink or grocery store sales of beer or wine allowed. The nearest liquor stores, even the state ones, were miles away as well.

We wouldn’t be here long but didn’t know it at the time. It’s where we began. Catholic elementary schoolkids played in starkly unadorned asphalted schoolyards at recess. As a rule, we boys played smear the queer for keeps. The queer was the one with a football who would attempt to break through to the distant side of the yard with the football. It was brutal, but it taught lessons.

Twenty years later, all of us could order a cocktail at a local restaurant or bowling alley, buy booze, beer, and wine without any clandestine efforts — we already had had the presidency. No one gave things to us. You had to take it and take your lumps. In other words, we learned to earn it.

We were never threateners, preferring gentle if not outright philosophical demeanors. We in the distinct minority who had parents with college degrees had picked up this shrink-like probing bedside manner used on us at the dinner table and taught it to our cohort who wanted to do the same. We learned to take interest in the world as we moved through it. It was as if we originally came from a different world and our survival and thriving in this one depended on close, continual observation and analysis.

We learned decided early on that no one should or would f*ck with us or ours, especially the weak, the small, the sickly, the birth defected and the girls. Anyone who screwed with us- or them- in particular paid. Bigtime.

One other thing — if someone came to school hungry, lunch bags and milk cartons were offered, no questions asked.

Subsequently, grocery bags full of food were then quietly and anonymously dropped off at their home’s front doors that afternoon after school. Those were our Mom’s rules from the depression. Moms rule.

Same went for school. No one was allowed to fail or get lots of D or E grades. No, it wasn’t cheating, although there was some of that — we aided each other by having the less sharp repeat certain things until they had committed them to memory. Doing acceptably good in school was the unwritten rule in our Diocesan school, since the academically advanced and the goodie two-shoe students were totally integrated with the less talented and poorly behaved. All boats would float. All these decades later after our departure, I’d call that a paradox in view of gifted and talented programs, IQ class segregation, tracking and other assorted teacher union bullsh*t now in vogue.

Some of us became altar servers or choir boys. We came to like our time in stained-glass light, wreathed in the smoke of incense. Anything that got us time out from under the withering gaze and ruler of Sister Archangella was a good thing.

We learned to speak and sing Latin, saw the dead in caskets, saw whatever sins committed in weakness forgiven publicly (sometimes overheard in the confessional box) at mass, witnessed lovers married and newborns baptized . . . and drank sacramental rotgut wine while cadging and smoking the good humored but aging monsignor’s smokes out back of the sacristy…

Some of us figured out as time passed but rejected that the Church wanted us in our place. Do this, don’t do that, kneel, stand, kneel, stand and so on. Some (more than a few) of us did not go for that sort of thing. That and other not so funny things.

Despite our acts of community assistance (solidarity?), we devilish parochial schoolers unknowingly and slowly embraced (without reading) James Joyce’s “Non serviam” as a mantra during the post Vatican II days. I finally read a decade later his Stephen Dedalus utter that Latin phrase. Years later, having volunteered, I was in the midst of career military service when Bob Dylan penned and sang Gotta Serve Somebody.

Our upbringing was like a rough un-refereed rugby game at end of which each day we’d give our competitors the finger. No one would look down on us regardless of whether our fathers were janitors, garbage collectors, cops, mailmen, engineers, teachers, or store owners or clerks.

It was as if we’d defiantly shout at them “No dickheads here!” in sorta a screwy tribal motto of excellence, distinction, honor, and integrity.

Cui bono?

We all did to one extent or another.

80+% of us had permanently departed by the time we were in our late 20s. College, drafted military service, love, rock and roll, drugs, marriage, and jobs, you know.

Decades later we survivors and thrivers had no rage issues despite some of our members’ situationally lower median IQs and egregiously bad choices.

None of us were superior, privileged, or hoity toity, but we all had tried our level best.

We all now had glasses and should have worn ear-protectors . . . since we made endless requests to have those around us repeat what they had just said.

We still playfully call one another douchebags but no longer pigpile the guy with the ball.

Anyone who struts his stuff instantly gets in unison a “Whoop-di f*ckin’ doo — look the f*ck at you.” It was and remains a style all our own. All of us knew the deal.

What an effing neighborhood and country.

The psychos, the muscles, the dumb jocks and the rock stars had passed (you knew who and didn’t have to be told). Still there were surprises as we shared the mug shots of those silent mousy types we’d protected when much later they were charged with multiple, some violent, felonies.

We missed the truly hilarious devils and toasted them repeatedly via shared email stories.

Like the others, a few of us had done our jobs and rose far by dealing in deceptions. But what we few never did was deal with self-deception. We always questioned everything, even that we knew as factual seven ways from Sunday. We worked inside malign-intent fortresses endlessly questioning everything.

Some have it nice. High ceilings. Original, century plus old, hard wood floors. Gourmet kitchens. Three car garages. A gilded few even have views of the ocean, endless mountain ridges, or down, out and over an entire city.

Some were as smart as organized criminals but never crossed the line. Allegedly.

We may be on our way out of the departure lounge to the tarmac, but all would do it all over again. Especially the early years. For each other.

Maybe that’s why we were the only people impervious to psychoanalysis, court ordered or otherwise.

All agree that the warm sunlight’s nice here at this stage.

Underneath all of our back-n-forths flowed this unanswered question — why are the hardest and best times of life always our last ones?

(Maybe) because we’re bored and tired and don’t give a sh*t? Or maybe it’s some supernatural sh*t we’re finally open to just before we begin our departure take-off roll.

——-

Out in the evening scented garden and wine glasses emptied, a bag of expensive cheeses and charcuterie plus an opened bottle of California red wine are on the granite kitchen island top.

W and I climb the rear deck steps slowly. We nod and pet the assembled neighborhood delegation of feral cats. We get to the door, and the kitties start to cry out in mock hunger, and we nearly crumple. But we get the door open and parade out their nightly gourmet dinners. They look up admiringly and see not salvation but a drive-through with plates of fast served food.

It’s the right thing to do. Gotta serve somebody, no?

Like with these furry ones, everyone and everything start off as complete strangers. It’s all in one’s commitment to get where they’re headed. That’s what counts.

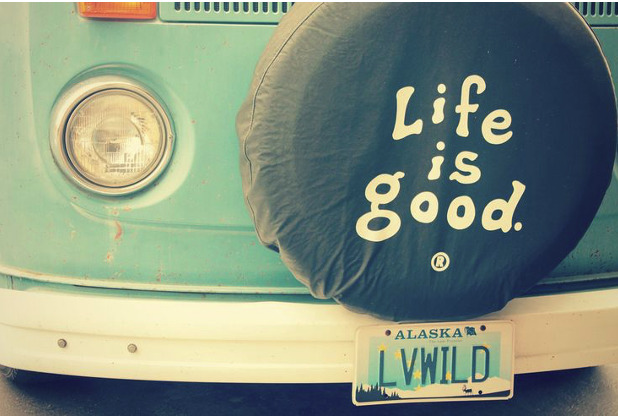

Life’s pulling the sword out of the stone good.

Copyright 2022 My Aisle Seat

www.vicsocotra.com