ERNIE (and Mac’s) WAR

This Spring Ahead nonsense with the clocks is kicking my butt. The computer is telling me it is past noon- and that is nonsense. Why do we not have the courage to leave the sun alone? Who is it in Congress that believe themselves as King Canute, waving not at the ocean in this case, but the hurtling blazing orb of Old Sol?

Vanity, vanity, thy name is Congress. Or something. I felt jet lagged right at the dinner table where the laptop lives.

I tried to look at my notes from the last session with Mac at Willow and they are not making much sense. Topically, the conversation veered from:

The Gruyere Cheese puffs, and the crackling Peking Duck pancakes, a nurses report from INOVA Fairfax that revealed nothing wrong, 50 miles covered in the champagne Jaguar, gall bladders, fried chicken done to perfection early in the last century, the obits of two men I did not know, the status of traffic on I-66 eastbound, and what the six fire trucks and twenty-five police cruisers were up to, Section 66 of the Arlington National Cemetery, and in-ground placement of urns therein, the deficiencies of the original Columbarium at the National Cemetery, the status of Katia’s job offer from outside the food, beverage and hospitality industry; whether the consolidation of the weather guessers, Cyrppies, Public Affairs and Intelligence Officers in the Corps of Information Dominance was ‘back to the future,’ since Mac had started as a special investigator who did PAO stuff at the Naval District in Seattle in 1941.

I was not making much progress on my happy hour white, since we were all over the map. “So you were really a Public Affairs officer before you were a codebreaker, right?”

Mac noded. “It was part of the Office of Naval Intelligence,” he said. “I guess they thought it was all information and pretty much the same thing.”

“Maybe they do again,” I said. I finally asked Mac about Chester Nimitz, the phlegmatic Texan who led the Navy’s drive west across the Pacific.

Mac was much more focused on this, and it was a little unusual, since the mythic figure of the Fleet Admiral normally was part of the backdrop to his war.

Mac furrowed his brow, attempting to distill the legend from the man. “Well,” he said slowly. “He took care of his Enlisted guys- the ones in the motor pool and the boat detail for the Flag Barge.” He went on to describe his conduit to the troops, who was a Mustang Lieutenant who had enormous impact on the staff and the way it worked.

I made a note to find a roster of the staff from 1945, and see if I could track down who the officer had been, since he showed up again as an agent of influence who secured the Junior Officer BOQ across from the HQ after the war- where the chapel is now. It was a rare name that Mac did not remember, or did after I was scribbling something else. I made a note to check it out and ask more questions.

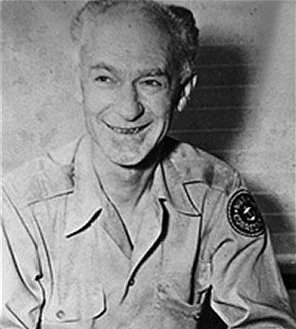

Mac was still contemplating the Public Affairs question. “It was interesting to see who came forward to Guam. Like Ernie Pyle, the legendary war correspondent.”

“He was the most famous correspondent of the War- probably more than Edward R. Murrow. Did you ever meet him?”

“Oh yes. He was on Guam before the invasion. Ernie was shot by a Japanese machine gunner on Ie Shima, Okinawa.”

“There is quite a display for him in the Hall of Correspondents in the Pentagon, and I would stop and read the panel display when I spent more time than I wanted walking to and from press conferences with The Joint Staff. Ernie was known as the soldier’s correspondent, according to the display. Did you ever have drinks with him?”

That is the way of these conversations- I had no inkling whatsoever that in the course of this session we would stumble across the most iconic and tragic media figures of the war in Europe and the Pacific, two theaters whose paths seemed rarely to cross.

“Not true,” said Mac. “Don’t forget Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, F-R-A-S-E-R. He came to the Pacific to command all British naval forces after commanding the group that sank the Nazi battleship Scharnhorst off Norway.”

“Point taken, Sir,” I said, and that led to a discussion of the wild four-day party that started on board Cagey Five, the battleship HMS King George V.

“But you actually met Ernie Pyle? That is incredible.”

The Admiral shrugged. “He was there, it was a small island. He had sort of prickly relations with the Navy, since he thought the sailors had it pretty cushy compared to the combat infantry of the ETO. He was a plain-spoken SOB and he wore his heart on his sleeve.”

“He might not have thought that if he saw the results of a running gunfight like the battle for the Slot,” I said indignantly. “I just read Neptune’s Fury, Jim Hornfischer’s account of the slaughter.”

Mac looked on with the cool perspective that only ten decades on the planet can give you, and know you are the last man standing from all the formations so long ago. “It is one thing to read about it and quite another to live it. Ernie had a point. He got bombed with our guys by the Army Air Corps at St. Lo, and was badly shaken. His heart was always with the riflemen of that war. In 1944, he wrote a column urging that soldiers in combat get “fight pay” just as airmen were paid “flight pay.”

Congress passed a law authorizing $10 a month extra pay for combat infantrymen. The legislation was called ‘The Ernie Pyle Bill.’ That was the mark of the depth of fondness the troops had for him.”

“Sounds like Bill Mauldin and his Willie and Joe cartoons.”

“Close enough,” said Mac. “And you can throw Andy Rooney in that group, too. Andy was one of the angry young men, then. Ernie was an old man, though- he was 45 when he was shot. I remember thinking about that at the time- I was still in my mid-twenties and he was old enough to be my father.”

“Do you recall how you heard about his death? Did you have to clear the dispatches or the pictures before they went back to CONUS?”

Mac shook his head. “Not that I recall. There was a picture I might have seen at the time, but it never was published. I think it was the middle of April in ’45. He went from Guam to Okinawa to cover the action. These days, you would say he was ‘imbedded’ with the 77th Infantry Division.”

“He took all the risks that the grunts did,” I said. “That is a commitment to the mission.”

“Yes, I think so. He was riding in a jeep with the CO on an infantry regiment and a couple other guys. Apparently hundreds of vehicles had driven the same road, but for whatever reason, a Japanese machine gun opened up on them. They stopped the jeep and everyone jumped into the ditch. Apparently Ernie raised his head to ask the Colonel if he was OK.”

“I think I heard he was killed by a sniper,” I said, stopping my scribbling.

“Nope, it was a Jap machine gun that had played possum, letting hundreds of other vehicles go by. Those were Ernie’s last words, though. He took a round in the temple, and was killed instantly right after he asked.”

“Maybe that is why the machine gunners waited, since they must have known that opening up would get them killed pretty quickly. That is a powerful argument for keeping your head down,” I said.

“Yes indeed. I am sure Ernie would have preferred for it to work out differently. They Army buried him with his helmet on with a bunch of the other combat dead. He was one of the few civilians to be awarded the Purple Heart.”

“Wait, I saw his grave at the Punchbowl in Honolulu!” I said.

“Ernie traveled a while after the war. They exhumed him from the grave in Ie Shima, and then buried him in the Army cemetery on Okinawa, and then finally they moved him to the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific where you saw him.”

“That is amazing,” I said. “He was the most-read correspondent of the war.”

Mac nodded and finished his Bell’s Lager. “He even impacted the Japanese. When Okinawa was returned to Japan’s control after the war, Ernie’s monument was one of only three American memorials allowed to remain in place.”

“Huh.” I fished around in my wallet, and the Admiral picked up the tab, which was modest since he drinks for free now at Willow.

We settled up with Liz-S and Jasper, the best bowler on Guam, went to find the Admiral’s walker, one of the ones with brakes and quick action movement. I walked back across Fairfax Drive with him until he turned off at the entrance to the Madison. I retrieved the Bluesmobile from the Bat Cave under the hotel and drove home.

Once I opened the mail, I poured a tall one and logged onto the ‘net. I checked out the Ernie Pyle Monument, in place for 67 years:

AT THIS SPOT

THE

77TH INFANTRY DIVISION

LOST A BUDDY

ERNIE PYLE

18 APRIL, 1945

Copyright 2012 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com