How We Got Where We Are

(President Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947 on board this aircraft, a VC-54C

Presidential transport, the first aircraft used in the role of Air Fore ONE).

We have wrestled with telling the story of how the Department of War and the Navy were disestablished and re-invented in 1947 alongside a brand new Department of the Air Force. It was a crazy time with the largest conflict in human history just concluded! There was more at foot and a Chilly Conflict to come with those Russians. The Navy and Army remained, but were augmented by the proud Air Force capable of delivering atomic weapons to any point on the planet.

(President Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947)

In 1945, specific plans for the proposed DoD were put forth by the Army, the Navy, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In a special message to Congress on 19 December 1945, a proposal went to Congress but was held up by the Naval Affairs Committee hearings in July 1946, which raised objections to the concentration of power in a single department. President Truman eventually sent new legislation to Congress in February 1947, where it was debated and amended for several months.

The Department of Defense, “DoD” was created in 1947 as a national military establishment with a single secretary to preside over the former Department of War, founded in 1789. The Department of the Navy (founded in 1798; formerly the Board of Admiralty, founded in 1780). The Department of the Air Force was also created as a new service (previously under the War Department as the Army Air Forces). DoD was created in order to reduce interservice rivalry, which was believed to have reduced military effectiveness during World War II.

On July 26, 1947, Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947, which set up the “National Military Establishment” to begin operations on September 18, the day after the Senate confirmed James V. Forrestal as the first Secretary of Defense. The Establishment had the unfortunate abbreviation “NME” (with a pronunciation virtually identical to “enemy”), and was renamed the “Department of Defense” (also described in the Act under “Title II – The Department of Defense,” and later abbreviated as “DoD”) on August 10, 1949.

There’s no reason for having a Navy and Marine Corps. General Bradley told us that amphibious operations are a thing of the past. We’ll never have any more amphibious operations. That does away with the Marine Corps. And the Air Force can do anything the Navy can do nowadays, so that does away with the Navy.

—Secretary of Defense Louis A. Johnson, December 1949

The debate that caused the “Revolt of the Admirals” had been building for several years, but climaxed in 1949 when many of those officers, including Chief of Naval Operations Louis E. Denfeld, as well as Secretary of the Navy John L. Sullivan, were either fired or forced to resign.

In November 1943, General of the Army George C. Marshall called for post-World War II unification of the Department of War and the Department of the Navy. His proposals also included the creation of a separate “Air Arm”, the United States Air Force. These proposals led to what became known as the “unification debates” and the eventual passage of the National Security Act of 1947. That Act reorganized the military, creating a unified National Military Establishment (renamed the Department of Defense shortly after), the National Security Council (NSC), Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and an independent United States Air Force (which became its own military branch after being part of the Army).

The generals of the newly-formed Air Force propounded a new doctrine: that strategic bombing, particularly with nuclear weapons, was the sole decisive element necessary to win any future war; and was therefore the sole means necessary to deter an adversary from launching a Pearl Harbor like surprise attack or war against the United States. To implement this doctrine, which the Air Force and its supporters regarded as the highest national priority, the Air Force proposed that it should be funded by the Congress to build a large fleet of U.S. based long-range strategic heavy bombers. The Air Force generals argued that this project should receive large amounts of funding, beginning with the B-36 Peacemaker bomber.

The admirals of the Navy disagreed. Pointing to the overwhelming dominance of the aircraft carrier in the Pacific Theater, they asked the United States Congress to fund a large fleet of “supercarriers” and their supporting battle groups, beginning with the USS United States. Her number was CVA-58. The Navy leadership believed that wars could not be won by strategic bombing alone, with or without the use of nuclear weapons. The Navy also maintained that to decide, at the outset of any future conflict, to initiate the widespread use of nuclear weapons—attacking the major population centers of the enemy homeland—was immoral.

The USS United States was, however, designed to support 100,000-pound aircraft, which would be large enough to carry the multi-ton nuclear weapons of the day. The plans for the United States-class called for eight ships carrying ten heavy bombers each and enough aviation fuel for eight raids per plane, allowing them to drop 640 nuclear weapons before resupply became necessary.

Some of us served in USS Forrestal, the first supercarrier constructed after the cancellation of the United States. Her number was CVA-59.

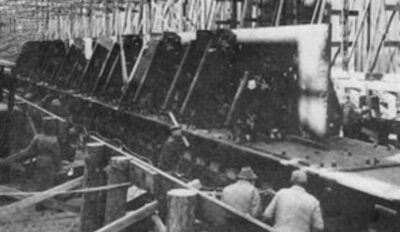

(USS United States, pictured in drydock with her keel laid. Photo USN).

The cancellation of USS United States and her sister ships were the major factor in the “Revolt of the Admirals.” There are two wars in process at the moment, three if you include the rocket and ballistic missile activity in the southern Red Sea. That is why we draw you attention to the Defense Act of 1947, and how we built the machine intended to protect us. Stand by. There is a little more to come!

Copyright 2024 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com