Getting Small

“I do take one drug now – for fun – and, maybe you’ve heard of it, it’s a new thing, I don’t know if you have or not. It’s a new thing, it makes you small. [ indicates size with fingers ] About this big. And, you know, I’ll be home, sitting with my friends, and, uh.. we’ll be sitting around, and somebody will say, “Heeeyyy.. let’s get small!”

– – Comedian and Banjo Picker Steve Martin from his monologue “Let’s Get Small” (1977)

(1973 GMC Chevy Vega Kammback GT Wagon. Photo Socotra.)

The Chevy Vegas were an answer to a question posed by the fellows at OPEC, and they were thrown together at the GM Assembly plant at Lordstown, just west of East Gate on the Turnpike in Eastern Ohio. I see the plant every time I drive up to Michigan, but it was far enough from Detroit that I could not get down there to see them put the Kammback GT Wagon together. There was a school of thought that if you actually were following your prospective ride along the assembly line it would improve the quality of the vehicle.

Stupid, I know, but I heard of people who watched their Mustangs being built at the Dearborn Assembly Plant-or D.A.P., as it is affectionately known at Ford’s. They built the pony car there since 1964, a run of 40 years, in good and bad times. 1973 was a bad year for Mustang, as it was for all the Hot Wheels line of performance vehicles. Gas cost too much.

I still think my Vega was a good-looking car. Certainly it was better than the competition, the Ford Pinto, which later was memorialized as the poster vehicle for bad fuel tank placement.

Lee Iacocca was the driving force behind the development of the Pinto, and there was a massive fight in upper management when Arjay Miller was kicked upstairs to be Vice Chairman of Ford’s Board, and Henry Ford the Deuce went outside the company to bring in Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen in to run things instead of elevating Lee, who was Executive VP of North American Vehicle Operations.

People like me were a growing component of the domestic market. We didn’t have much in the way of disposable income, and Iacocca saw what we were driving: VW Beetles and those strange little Japanese imports. Knudsen and Iacocca had dramatically differing world views, and in the end it was the Oil Sheikhs who determined that Lee was right and Bunkie was wrong.

The Pinto- and the Vega competition- were based on the proposition of the rule of “2.” The cars ought not to cost more than $2,000 and not weigh more than 2,000 pounds. They had to be fast enough to drive on the interstates but easy on the wallet for maintenance. There was nothing really fancy about the Pinto. Its main goals were to provide reasonable comfort and adequate performance.

“Adequate” being a sort of anemic four-cylinder replacement to the MoPar screaming V8 Hemis of just a couple years before.

The lines on my Vega were sleek: ’73 was the last year the Feds did not require those ugly rubber energy-absorbing bumpers, which were ugly as sin and didn’t really catch up with the rest of the design for years. The mini-wagon design flowed nicely and gave a lot of room to throw stuff in the back, sleeping bags and old liquor boxes filled with LPs and college textbooks for the job.

The 1973 Vega model year featured over 300 changes from the 1972 model year, and they needed most of them, including new exterior and interior colors and new standard interior trim. I ordered the tan interior and British racing green for the exterior paint, and had every intention of highlighting the snout with some after-market Cooper yellow for emphasis that I never got around to applying.

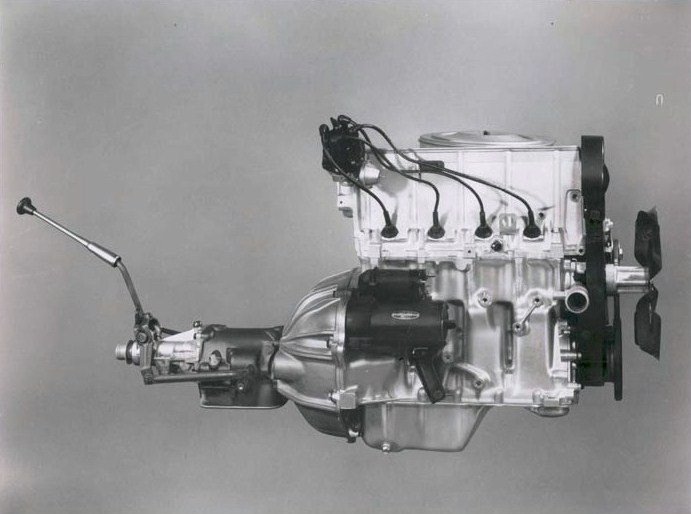

The four-speed manual shifter was from Saginaw Steering Gear, and a new shift linkage replaced the Opel-built units that GM imported from their European subsidiary. The L-11 engine featured a new Holley staged two-barrel carburetor, but the engine itself was the problem, not the solution, of the Gas Crisis.

I specified the BR70-13 white-stripe steel belted radial tires on my order and thought I was pretty cool rolling down Woodward or the Cass Corridor in my little car. It was quite a change from the muscle beasts in which we learned to drive. Small was beautiful in the days of the even-odd gas lines, a thoroughly un-American restriction on our traditional ability to drive anywhere at any time.

Much as I liked it, the Vega was a piece of crap. It burned half a quart of oil for every tank of gas, just like clockwork. It was not shoddy workmanship, though, it was the simple fact that the Vega engine was not ready for prime time, which was true of the whole industry that year.

GM Research Labs had been working on a sleeveless aluminum block since the late ’50s. The incentive was cost. Engineering out the four-cylinder block liners would save $8 per unit. Reynolds Metal Co. developed a custom alloy suitable for faster production die-casting.

The Sealed Power Corp. developed chrome-plated piston rings specially blunted to prevent scuffing. It might have been a successful design, with a little more time for development, but the OPEC embargo prevented that. Demand for fuel efficiency was suddenly really important and the engine was rushed into production.

Who could have imagined that V-8 powered Detroit would suddenly have an immediate and pressing need for four cylinder engines?

I tried driving 55 on I-75 the morning after President Nixon announced how important it was that we conserve energy. I was nearly run over by a Buick hurtling toward the Livernois exit. I was so young that I took things the President said seriously.

After that, I preferred to motor more sedately down Cass when I visited the Wayne State University campus as a textbook salesman for the McGraw-Hill Book Company, my first real job after college.

Cass Avenue runs parallel to Woodward, which is the golden road out to where white Detroit was fleeing, out toward Grabbingham and Bloomfield Hills and the mansions of the car people. Cass runs from Congress Street, ending a few miles further north at West Grand Boulevard.

(Detroit’s famed Masonic temple. Photo Wikipedia.)

Significant landmarks along the fourteen blocks that constituted the Corridor included the Detroit Masonic Temple, which looks like a church but is actually the world’s largest Masonic structure, sadly down at the heels now, and Cass Technical High School and the small but densely-packed Chinatown. The architecture was 1930s-industrial, for the most part, interspersed with low apartment buildings and tons of bars and restaurants.

(Cass Tech High School’s old building.)

In 1973 the city was not dead yet. The Corridor reflected the tipping point of the population that was shortly going to be overwhelmingly African American. I was out in the maid’s quarters of a mansion in Palmer Park off Woodward. Closer to downtown, the neighborhoods around Cass Avenue featured hangers-on from the great Appalachian migration that came to work in the Defense plants during the war, and there were newer pockets of Hindus and Native Americans, burned-out hippies, students from Wayne State and single-moms struggling to raise their kids.

Immigrants from India, Pakistan, China, Korea and the Philippines were part of the mix. Many worked at the Detroit Medical Center, a group of hospitals just across Woodward Avenue.

Detroit’s small Chinatown was located at Cass and Peterboro in the southern end of the Corridor, and there was often a wait for tables at lunch at the Chinese restaurants, if you can imagine that now.

That was during the day. The proximity of Cass to Woodward, Detroit’s main artery, had made Cass the logical area for the local authorities to push local drug activity, prostitution, and general civic indecencies away from the downtown.

Long-legged, high-heeled hookers prowled the sidewalks outside world-class dive bars like Jumbos, The Sweetheart, Willis Show Bar and Anderson’s Gardens. The Gold Dollar Show Bar advertised “Female Impersonators Nightly.”

Crazy was OK. Prime-time sidewalk shows featured the working ladies who would flash their breasts at the Johns driving in from the suburbs, their pimps, winos, scammers, dopers and dealers.

The bars- particularly Anderson’s Garden, all paid for active police protection, and despite the seedy nature of the neighborhood, I never felt bad about going down and hanging out. I used to love to take visiting Book Company people down to the Corridor when they came to look at my territory. It gave them a thrill, but I knew the place was 100% safe.

At least it was then. As inauguration day rolled around for Coleman Young, and as Dick Nixon lurched through the last anguished days of his presidency, things were about to take a dramatic change, courtesy of the scourge of crack cocaine. But that was just another step toward the abyss, and frankly, we were worried about other things at the time.

The Cass Corridor was sort of the anti-Woodward: you couldn’t mistake me in my green Vega for the preppie Grabbingham kid in the screaming red Charger R/T 440, that was for sure.

Copyright 2014 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303