A Future in Steel

First day of December- damn! How did this happen? It is chill here in Arlington, though not the kind of cold that penetrates the bones in the fresh breeze off the Big Lake and the Bay. A trip to Harbor Springs has always been one of the things on the list to do when I am Up North. They have some nice galleries, and the restaurants feature planked white fish and garlic mashed potatoes along the view of The Little Village across the Bay.

On my last visit to Raven at The Bluffs this trip I turned right out of the parking lot on M-119 and rolled down the hill into town. On the left hand side is a green cast-iron historical sign in front of an odd private residence. It is worth pulling over to take a look at the hexagon-shaped home of an American original: Mr. Ephraim Shay.

Like my Great-great-grandfather, Shay enlisted in the Union Army at the beginning of the Civil War, and like James Socotra, he agreed to a three-year enlistment. No one expected the conflict to go on for more than a few months, if that, and thirty-six months seemed excessive. Shay decided not to accept the handsome re-enlistment bonus, and returned to Michigan in 1864 to seek his fortune in the Northland. James Socotra accepted the bonus and signed up for another hitch. The 30-days leave incentive that came with the re-enlistment gave him the chance to spend some time at home with the woman who would become my great-great grandmother, and she convinced James that the war could go on without him.

He opened a store, and practiced war no more. He was not known for much else,

Ephraim Shay was a tinkerer in the tradition of Thomas Alva Edison. The American attic is filled with inventors. Shay’s specialty was metallurgy: mostly in the fields of cast iron and steel. He developed a unique locomotive that could run on wooden rails, a huge breakthrough that enabled the logging industry to clear-cut the remaining old-growth pines of the lower peninsula of the Wolverine State.

Before there was tourism, there was the race to harvest the vast forest of the north. The strange hexagonal house in Harbor Springs came after Shay established his work-shops at the east end of Harbor Springs. The Hexagon is the last remaining building in the complex, and is perhaps the most significant in the tradition of American inventiveness.

Where Edison thought that houses might be constructed in a one-pour operation from concrete, Shay thought another material might work better. His stamped-steel Hexagon was thrown up in 1892, a decade before the Wizard of Menlo Park experimented with casting homes in one smooth operation.

Edison’s scheme produced only a hundred houses, but there was only one Shay Metal dwelling, and it is a fascinating thing to see. What killed it? I don’t know. Lack of a sound distribution and marketing plan, I suppose, or public skepticism about living in iron.

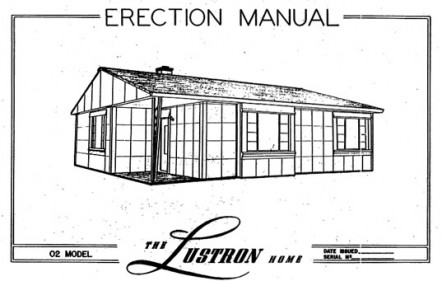

The vaguely gothic shape of Hexagon House is not what the people at Lustron were looking for. The engineers at Lustron aimed to harness the power and energy of the war production plants to meet the housing crunch caused by the return of The Boys from overseas.

You can see a kindred spirit in the famous B-29 lines of the original Airstream mobile homes. They still look slick, don’t you think?

Anyway, if I had not got lost with Mr. Ephraim Shay this morning, I would have told you about how Lustron went south, and where you could have seen one right here in DC. Actually, still can, since there are two remaining out of more than a hundred down at the Marine Base at Quantico.

Regrettably, I am out of airspeed and ideas all at the same time, and will have to get back to you tomorrow about the vision of an all-steel future.

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com