Arrias: Let’s End Civilian Control in the Pentagon

Okay, not really.

Okay, not really.

But, there’s been lots of talk about “military” vs. civilian control, with 3 retired officers (3 civilians) selected for senior positions in the Trump administration. Hmmm…

First: they’re retired. They were in the military. We’ve had retired military serve in government before; it’s never been a problem. In fact, 60 years ago a guy on active duty occupied the Oval Office.

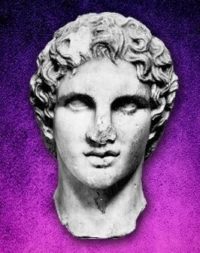

Eisenhower, a 5-star officer, was on permanent active duty. Interestingly, Eisenhower was perhaps the most vocal critic of Pentagon ‘overreach,’ the man who coined the term – as a warning – the ‘military-industrial complex.’

But there’s another issue, and it’s central to any effort to improve efficiency and effectiveness in the Department of Defense (DOD) – or the rest of government: the Civil Service.

Some history…

Prior to 1883 federal jobs weren’t protected. Every civilian employee could be fired at “the pleasure of the President.” A “spoils” system developed, jobs turning over with every president. But, the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act (1883) made hiring, retention and promotion a merit based process.

The concept is sound; the system functioned well throughout much of the last 100 years. But, now there are problems, centered on two issues: First, the number of federal civilian employees. In DOD alone there are 750,000 civilians. That compares to 1.3 million Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Marines. In World War II there were 2.6 million civilians in the Departments (War plus Navy), compared to 13 million in uniform.

Since 1971 the total federal civilian work force has outnumbered those in uniform. In 1999 the civilian work force was double the number of military personnel, though the number in uniform grew a bit after 2001. By 2014 we were back to 2 civilian federal workers across the government per each Soldier, Sailor, Airman and Marine.

What isn’t apparent to those who’ve never dealt with it, inside the services these civilians have a great deal of real power, much more than it might otherwise appear. There are two reasons for this. First: those in uniform cycle in and out on 2-3 year orders; ‘back to the fleet,’ as the Navy says. Because real power in Washington is in budgets, and budget cycles are complex, multi-year issues, if you’re present for 2-3 years and then you leave, you’re going to have less impact on things then you might suspect.

The second issue is bureaucratic. If a general finds a senior civilian who opposes certain changes, and is passively resisting, the general’s ability to move around or bypass that individual is less than you might think. In many cases it’s effectively zero.

A friend of a friend – a pilot, 2-star officer – is responsible for weapon system acquisition. Despite titular authority service intentions are routinely frustrated by careful and subtle stalling and manipulation by civilian personnel who disagree with the general’s course. Knowing they can’t be fired, and that, in a year or two, the general will be gone, they simply hang on, drag their feet, and prevent change.

That is the real civilian control of DOD. And it’s extremely expensive.

And it’s also apparent that a majority of the civilian work force in Washington DC aren’t supporters of Mr. Trump, and they will ‘slow-roll’ his appointees.

So, what can be done?

1) Fundamentals of civil service reform were, and are, overwhelmingly correct. Hiring and promotion based on merit is the obviously correct answer. But…

2) The civil work force is too large. While automation has made irrelevant many administrative positions, the federal government, and DOD in particular, abounds with large, complex staffs and huge administrative offices. If these offices clearly provided increased efficiency and effectiveness in procurement and management of DOD programs, they might be defended. But the opposite is true.

Many offices report things no one cares about, to people with no real authority. We need to ID and eliminate billets, reports, processes and functions that benefit no warfighting requirement. Where appropriate, move them out of Washington.

3) For SES and GS-15s the law must be clarified: within the context of their job, a legal order from a superior constitutes a legal requirement. Failure to conform is therefore either an indication of incompetence, or willful disobedience. Either should constitute grounds for dismissal.

Finally, employment by the US government isn’t a right. The administration must work with Congress to identify means to reduce the civilian force, identify and remove personnel who’ve risen past their level of competence, and tightly focus DOD on warfighting.

Copyright 2016 Arrias

www.vicsocotra.com