Banneker Park and SW9

(What remains of SW9 is a one-foot square sandstone block, extending about 18 inches above ground and probably about 2 feet underground. Image Loop202).

So, leaving the history of the American Nazis behind (don’t worry, we will meet some of them again in our quest to follow the path of Major Andrew Ellicott) we head northwest to Benjamin Banneker park, and the SW 9 Intermediate Boundary Stone.

It is a fairly straightforward journey. From below the big water tower, head northwest toward Wilson Blvd and turn left, for a third of a mile and then turn right onto Roosevelt Blvd. Proceed about a half mile until you come to North 16th Street and turn left. Continue on as it turns into E. Columbia Street for four hundred feet and turn right onto North Van Buren. The Park will be on your right, and the Stone is located on the northwest corner near 18th Street.

(The SW9 Stone, shown above in its signature DAR cage, is in pretty good shape, all things considered. The inscription of the word “Virginia” is still visible in elegant script. Photo above Google Street View. Below courtesy 2015 by Steven Powers).

Now, of course, it only marks the borders of Arlington and Fairfax Counties, but in its day it marked the national boundary of the only territory specifically allocated to the Federal Government. Never mind that it seems to think it owns all of it and everyone in it, but things have changed a little bit since Major Ellicott and his hardy team plowed into the underbrush to mark the new capital.

There were some things that were already in the area as the Major’s party approached- notably the City of Falls Church, which was about to be divided into a Virginia side and Federal Enclave section. The town was named for being the closest established church to the falls of the Potomac River, and dates to the mid 18th Century, where it has served as a place of worship, recruiting station, hospital and (briefly) as a Union stable in the Civil War.

In the time of the Boundary Stone project, Major Ellicott’s men would probably been more interested in the taverns. The first structure in the village was a log tavern known as Big Chimneys, erected in 1699 by a settler squatting on the land-grant belong to Lord Fairfax. By the time the Stone was placed, there were many log cabins, two churches and two taverns, an appropriate and proper ratio.

(“The Falls Church.” Image by Southerngs via wikicommons).

The most historic structure is The Falls Church, of course, which flashed briefly into prominence when the Congregation split following years of internal doctrinal conflict. The main issues involved Biblical authority, the nature of human sexuality, roles of men and women in ordained ministry, and liturgical reform.

In December 2006, a substantial majority of the congregation voted to disaffiliate from the Episcopal Church in the United States of America and joined the Convocation of Anglicans in North America, which for some reason is sponsored by the Church of Nigeria. I gather it is something about a more fundamental approach to the faith, and it injected the topic of race into an otherwise purely internal theological discussion.

The topic of race is never very far way in Northern Virginia, the legacy of the plantation culture on one side of the Potomac and The Free State of Maryland on the other.

The American Nazis and the Klan used to demonstrate in Arlington after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, in fact at the community pool in the Buckingham neighborhood where I have lived the last fifteen years. The answer then was to close the pool and sell the property to the Mercedes dealer who occupies the property now, but things were changing rapidly.

By 1976, pressure mounted from the Afro-American Bicentennial Corporation to name the park for the African American surveyor, mathematician and astronomer who assisted Ellicott during the first three months of Ellicott’s 1791-1792 survey. The Park was re-designated in his honor, and SW9 was placed as the first of the Stones to be included in the National Register of Historic Places.

Banneker is a celebrated figure now. He was born a free man on November 9, 1731, in Baltimore County, on a farm located within a mile from the present Ellicott City. His grandmother was a white Englishwoman who had been arrested for a minor criminal offense against the King’s decorum. She was ordered to be transported to Maryland as an indentured servant as punishment. She was an enterprising woman. After serving her period of indenture, she developed a small farm and purchased two slaves, both of whom she subsequently freed. She married one named Bannaka and together they had four children and worked the tobacco plantation for the cash crop.

The couple’s oldest daughter was named Mary, and she married Robert, a freedman originally from Guinea. Robert took Mary’s name and their first son was Benjamin Banneker. Banneker had had relatively little formal education, though his grandmother had taught him to read from a Bible, and there were several winters in which he attended a small country school. He was an avid reader and fascinated by mathematical puzzles.

He continued his education as an autodidact as he could acquire reading materials, The Ellicott founded a mill community at Ellicott’s Lower Mills (now known as Ellicott City), and Banneker became acquainted with them was George Ellicott, the young son of one of the founding brothers.

George was experienced and had re-surveyed the Baltimore Turnpike in addition to surveying developed an interest in astronomy. He acquired a number of works on the subject, as well as observational instruments to conduct his own research. Banneker’s interest was piqued, and he several of the texts and instruments and quickly mastered them.

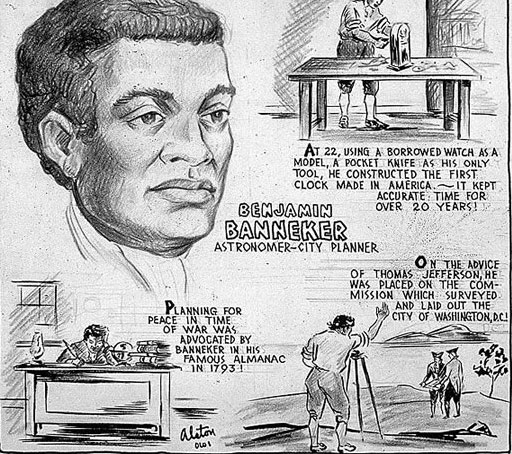

(This Charles Alston Biographic sketch of Benjamin Banneker invokes some of the legends that have risen around him. Copyright Charles Alston).

Getting along in years by the time of the District Survey, his ability to work the farm was diminishing, and he threw himself into his new occupation, completing the manuscript of his first practical almanac in 1790. Prospective publishers circulated it, and Banneker’s accomplishments became a matter of attention for Andrew Ellicott as he cast about for an able assistant. His brothers were occupied either in Commerce at the Mills, or completing a survey of the Western Boundary of New York State, and in view of the urgency Secretary Jefferson had placed on laying out the new Federal Enclave, he needed help.

Banneker had recently retired from farming due to failing health and he threw all his energy into his studies and calculations. He was the only man with the necessary skills available. In the course of conversations with Jefferson, Ellicott advised him that Banneker was the man who could serve as the assistant surveyor. Jefferson bought into the idea after seeing the work for Banneker’s almanac, at lest until the younger Ellicott Brothers were available to join the project.

The rest is history. Banneker was “greatly excited by the prospect,” and packed to join Ellicott at Jones Point to identify the baseline cardinal South Stone. It was the first time Banneker had traveled more than ten miles from his farm. While his presence was probably limited to the base camp at Jones Point for the initial plot of the District, his attention to detail and accuracy of his observations contributed greatly to the accuracy of the ultimate placement of the forty Stones of the District.

So, today, the Ellicott brothers have a city named for them, and Benjamin Banneker has his Park, which SW9 still proudly proclaims the Jurisdiction of the United States and that of Virginia.

Tomorrow we will visit the coolest of the Stones, if not the wildest, as the cardinal Stone of the West.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303