Big Engines in Little Cars

Thus has it always been for the Car People of the vast Heartland of America: big engines stuffed into little cars.

After a recent over-indulgence on high-test muscle cars, a pal up in Alaska wrote to remind me that big engines are not the sole province of snotty suburban kids with connections to the auto industry. Americans have always stuffed the biggest engines into whatever it was that happened to be in the driveway.

My pal is married to my Fleet buddy Roger, and she said: “They pulled the hulk of a 53 chevy truck out of a Lemoore, California junkyard, and from that same junkyard, rebuilt it with new parts and a huge,ove-rpowered engine. I wish I could remember what he said it was, but the truck would almost do a vertical takeoff when finished. They drove it until they deployed to Vietnam (again) in ’70. Anyway, Roger is driving down the street in Anchorage and he sees what looks very, very similar to his truck. He keeps passing it every day until finally he gives up and goes inside the business to talk to the owner. Who says his brother bought it in Central California, shipped it to Washington State, where it proved inadequate for Seattle traffic, and then this guy bought it from his brother and shipped it to Anchorage. Roger sits inside it, and discovers the same junkyard shift knob they put on the truck in the first place. Small world, eh?”

It is a small world, at least the American version of it, and there has always been an inclination to supersize things. I was going to start with the Nash Healy, a curiosity these days, since Dad liked them a lot, and Estel, the master tool and die guy from Ford’s family had one. It was a very cool thing, I recall, to sit in and move the levers before I knew what any of them really did.

They were not foolish enough to have the keys in the car.

(This is the Nash Healy from the year of my birth. Photo Hemmings).

The Healy was a product of a chance meeting between Hudson-Nash President George Mason and British car guy Donald Healy. They met on the eastbound transit of the Atlantic on the RMS Queen Elizabeth. Healy had been to American to try to get Cadillac engines for his new sports car, but Generous Motors was not interested. Mason was, and along with an enduring friendship, the rights to purchase the Rambler Ambassador drivetrain to stuff into his automobile.

Anyway, that sort to thinking is completely in keeping with the madness of the car guys who took brand new production cars and replaced their engines, transmissions, drive shafts and rear ends to produce cars ready to rock and roll right out of the box with the first turn of the ignition.

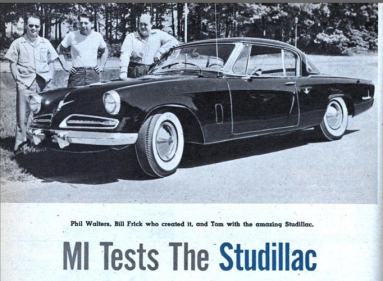

We ran into that early on, when the Ian Fleming’s James Bond waxed eloquent about them. Fleming had his CIA agent Felix Lieter drive a fictional version of something that had impressed him for real on a visit to America: the Studillac.

—a Studebaker Hawk amped up with a powerful Cadillac engine. So in a way, George Mason trumped GM with his Healy partnership chronologically, even if Healy wanted that Cadillac in his sleek sportscar.

Back in the day, legendary car writer Tom McCahill went out to review one for Mechanic’s illustrated, and the story is good enough to stand as a preface to the greatest factory hot rod guy in history, Carroll Shelby, whose ACs and Ford conversions stand as the most successful example of Factory rods ever.

(Carroll shelby’s immortal Cobra. Photo Classique Antique).

But I was talking about the Studillac, wasn’t I?

McCahill traced the magic of the car to Raymond Loewy, Studebaker designer and chief stylist. He had strained against the intellectual straitjacket of the industry standard clunky sedans and by 1953 was out with a car that made the “typical monsters of Detroit look as modern as Ben Hur’s chariot in a stock car race.”

McCahill went on to gush about the looks. He said: “The 1953 Studebaker has the looks of a moonlight night in Monte Carlo and literally drips with swashbuckle and intrigue.”

That guy could write. And he thought that the power-plant was acceptable and peppy. The steering reminded him of the popular British two-seater of the day, the MG-TC model. “Positive, but a little on the hard side.” He did not like the torque converter transmission which “sapped the torque of the small Studebaker V-8 engine, just the way rubber boots would slow up a tournament tennis player.”

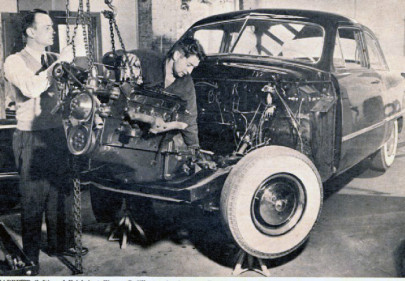

There was an alternative to what Studebaker considered an optimal engine and drive train, and that solution was available from Bill Frick, the man who made the Studillac. He was no stranger to this game of stuffing biggest dinosaur conversion units into small flashier cars- an earlier mutation had been known at the Fordillac, which he claimed could run away from a Jag XK 120 Jaguar “as if it were a highway sign.”

(Bill Frick and Phil Walters install a brand new Cadillac OHV V-8 engine in a brand new 1940 Ford. Photo courtesy of The Hemmings Blog).

In 1953, Frick decided the bold designs of Raymond Loewy were the future, and started to produce Studebaker Starlight and Starliner coupes powered by the 210-horsepower Cadillac engines. The modified Studebaker “combined the grace and beauty of the Studebaker Starliner with the power-packed performance of the new Cadillac engine,” according to the advertising literature.

McCahill noted that if you really wanted a bomb, you should try one of Frick’s Frankencars.

“He spends the first few days fixing the stock Studebaker quality-control on the body and trim. Then he pulls the whole rear axle assembly and drops in a new heavy-duty unit from Mercury. This gives Frick’s Studie 11-inch rear brakes instead of the standard 9-inch, and a much more robust structure. A larger radiator core comes next, to accept the increased requirement for coolant. Frick then trashes the Studie stock engine and swaps in a standard 1953 Cadillac V-8 engine.”

The Caddie engine only weighed fifty pounds more than the stock engine, and with the additional weight on the rear axle, the center of gravity equation stayed about the same, leaving the handling in good shape.

This little Frick magic turned the mild car from South Bend with a wild exterior into a “sports coupe that will match nearly anything in the world in getting down the highway.”

McCahill notes that the “stock Cadillac engine… just loafs in the light Studebaker chassis and should outlive a new-born colt by about 20 years.”

Cost? A trip to Frick’s garage would get you a Studillac for around $4,500. Zero -to-60 ET’s at 8.5 seconds, top speed 125+. “The regular Studebaker is one of the best looking rigs and, if you are getting a little fed up with family carryalls, I suggest you try one. For four people it is big enough and the trunk will hold enough baggage for a short weekend for all four.”

I finished the article missing Mechanic’s Illustrated almost as much as I mill tom McCahill. And I could not think of $4,500 better spent.

There was more, of course, and once everyone got the bug to go fast, there was always someone to accommodate. If I get to it, we ought to talk about the coolest street hot-rod American Motors ever tried to sell, the

At least until we had to pay for our own cars, and the Beetle showed up in the driveway. More about that- Hippies and Their Cars when we get there.

Copyright 2014 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303