Big John

There has been a lot of recent talk about something we have discussed with some energy for a very long time. Can’t get away from it. The content of that pigment in our epidermal layer is a determining feature of every momentary issue. It drives all functions of interaction. It is a symbol richer than its color and incorporates aspects of all our social interactions.

We have been told about things like ‘inherent fragility’ and the rest of the list of narratives that go with the George Floyd death.

It has replaced the concept of “class” in our discussion of how we all get along together. I have disliked the concept of class conflict since I first learned of it. That was sixty-odd years ago. One of the people who taught me about it happened to be melanin blessed. He was also male, a matter of some dispute in today’s divisive discourse. I never paid much attention to what I was being taught, since that is not how the process works. Mom represented the Irish side of the family, and one of the myriad of lessons she conveyed was what it was like to grow up in an Irish working-class family in the days after her father came back from the first big war overseas. He then raised a family with a very nice lady who we all got to know well as Grandma. She was warm with us but never talked about how we all came to be who we were.

A pal back in mid-school came from a family that was in the business of selling goods to a prosperous suburban town just outside muscular Detroit. We met in school, part of the cadre orientation for a generation hitting 70 years of age this year. Our pal’s Dad was amenable to hiring us to do chores at the department store- actual jobs. I recall there was some waiver we had to acquire from the town- we called it “working papers.” We had to have them to prevent exploitation by the capitalists due to our age, which was then 15. We were useful. The minimum wage at the time was just shy of three bucks an hour and going up. It was a princely sum in 1966-era America.

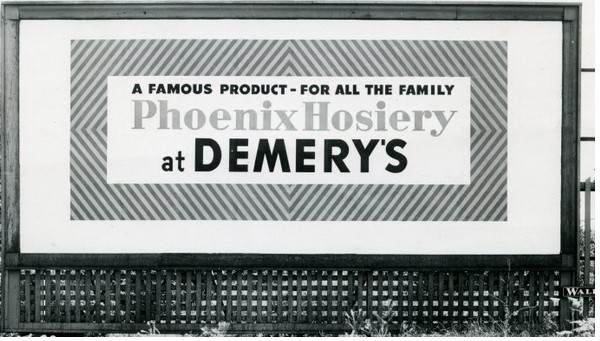

Our cadre was not old enough to be representational for the company on the sales floor. We were useful for simple tasks like moving stuff around, from trucks backed up to the loading dock at Demery’s Department store. Delivering boxes to the various departments in the store. Sweeping up. And working to keep tidy the parking lot to next to the building. That is how I met one of my first real bosses. He was named John Minter, and he was a very large male blessed with a high melanin content. We were told to address him as “Big John,” not “Mr. Minter.”

His primary work assignment was running the parking lot. There is a fair amount of overhead involved in managing a black-top covered rectangle in a moderately dense city environment. The store Manager, a man whose name escapes me now, took a look at me and decided I would be just right to become the parking lot assistant. It was so that Big John could take periodic breaks from the vertical aluminum box that guarded the entrance and exit lanes. I was deposited one morning at Big John’s shack, and told to do what he told me to do.

That was my personal introduction to the organized world of work. Big John was something new to me in the suburban world. He was articulate, opinionated, and fun to be around. I wish I had a picture to show you. His head was shaved and his features sloped into massive shoulders and massive arms. He had a belly that fit well on his imposing frame. He normally wore a shirt with the Demery’s logo embroidered on the left breast to identify his position and authority in the lot.

You may not recall the times, which is both good and bad. Murder bracketed our teen years. We heard of the assassination of our President on the loudspeaker at our middle school. John Kennedy had been sort of magical for us, so you can imagine the rection. He made a dramatic appearance on the national stage. Young, compared to his predecessor. Hatless in his inauguration parade. A practitioner of a religion with ties to a man in Rome. I don’t think any of us understood the context of the strange allegations against his religion.

Mom used to take us to swap-meets, where she occasionally found something useful to run her house. We kids found all sorts of curious things, wrenched out of their living times and consigned to old boxes that smelled of disintegrating cardboard. On one sunny weekend foray I discovered some yellowed magazines, undisturbed for decades. Glancing through them I saw cartoon images of distorted figures in clerical garb. It took me a moment to realize what I was looking at. The biggest of the images was the Pope, apparently working his malign plans to ungrateful Irish in America from a land far away.

At the time, our next-door neighbors on Chester St. were the Smiths and known to be devout Catholics. The strange message in the old magazines was hard to reconcile with the reality that I knew. I asked Mom about it and got a short-hand orientation to how her family had been treated in a time now a century ago. She was accurate but curt.

Now, some of that social unrest is back. I got a similar course in history from Big John. Detroit was the belligerent host to two summers of trouble. In 1967 it was a response to a Police crack-down on an unlicensed seller of after-hours liquor and occasional purveyor of illegal gambling. It became something that reflected local dissatisfaction with housing policies and discriminatory lending practices and a variety of social ills. Big John lived in Detroit, just a few miles down the road. His neighborhood was one of the areas affected by disturbances big enough to bring the 101st Airborne to the city to restore order. Someone’s order, anyway.

Big John told me about it, and his was the only dissenting source of information available that nervous summer. One afternoon he told me of sitting on his porch with a shotgun, just in case. He also taught me necessary parking lot skills- how to unlock cars without a key is one I still could use for years later until technology overcame the useful advantage of an unfurled wire coat-hanger. There were others, directly related to the movement and charging the owners of the vehicles for time spent with us. There were other issues he described only in passing, knowing that I did not understand the complexity of the world in which he lived. It wasn’t the point of his teachings. It was just context from his view on the porch.

I had turned sixteen the next summer, and by then my appearance was representative enough to be assigned to a job facing the public in the Men’s Department. I was supposed to be a walking model of the clothing the store was trying to sell. Call it a sort of “outreach” these days, but that was hardly what was on our minds in the summer of 1968. Dr. King’s murder was the key moment that changed everything everywhere. It was bigger than the George Floyd protests this last summer. 110 U.S. cities had the same sort of unrest, flames burning through the night everywhere.

Big John’s impression of the events of the day was a pivotal moment in my education. A summer with him, sometimes in the confines of the aluminum booth in the rain, had been an unexpected gift. The next year I stopped to talk to him when crossing his lot to punch in on the loading dock. He told me what he thought was going on, and in a bold move, told me of his plan to have the Department Store dispatch him for representation at Dr. King’s funeral in Atlanta. That was one of the first demonstrations of a new awareness I had run into, and years later I thought of Big John’s presence while looking at Dr. King’s Tomb.

So this brilliant Piedmont morning, I was thinking about our current social trevails with the memory of past ones from my first supervisor in the world of work. And then I had to think of one of the last. He was a four-star Army general serving as one of the better Chiefs of The Joint Staff in a complex world. I wound up playing only a minor part of his morning, but had a chance to absorb some of the common wisdom he shared with his staff. It reminded me of many things I had learned since Big John. And I think both would have had the same sort of reaction. I think they might have done a quick shrug and a glance and figured out how to best play the situation. They were absolutely confident in their ability to succeed in any world they might find themselves.

That is just one of the lessons they taught me. And I think they might have had a good but ironic laugh about America today.

Copyright 2021 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com