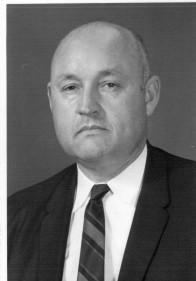

Big Smoke

04 February 2013. LCDR Thomas J. “Big Smoke” Duval, USN-Ret., at a nursing facility in Berkeley Springs, West Virginia. Born in 1927, Tom made his home in the DC suburb of Arlington after retiring from active duty and joining the staff of the Office of Naval Intelligence and a second career in the shadowy Task Force 157. In his civilian life, he had many covert and clandestine HUMINT missions, and was an associate of legendary convicted arms trader Edmond Wilson. I had the priviledge to work on some of his remembrance of operations long past- though I touched a nerve when I started asking too many questions. He was preceded in death by his wife, Lois Wells Duval, and despite a hard search, I could not find a decent obituary.

There is no one alive now who knew all his secrets. Big Smoke lived a big life, and as his generation leaves us, I thought I might let him tell you a story himself.

Imperial Japanese Troops surrender at Yokosuka, 1945. Photo USN.

“I am a burly, bullet-headed old sailor now, but of course I wasn’t always. In 1944 I was seventeen, the first year I was eligible to serve, with my parent’s consent, and I went down to the recruiting station at the first chance I could after my birthday to sign up for the Navy.

I made it through boot camp and out to the Pacific the next year, before it was all over, and I made Bos’un Three in the Deck Department a month before all promotions were frozen, and Operation Magic Carpet began to fly all the millions of servicemen home from the places they had fetched up when the shooting stopped.

As a new kid, I was there through the uneasy period of the occupation that began in September of 1945. What would it be? Guerilla warfare?

It was not. The Japanese accepted their new Shogun with fatalism when he flew into Atsugi base. A day later he drove in a motorcade down to take up his duties as the Supreme Commander on the top floor of the Dai Ichi Insurance Company headquarters, one of the last suitable buildings still standing near the Palace.

Japanese troops lined the roads, their backs to the passing cars. There would be no organized military resistance, though there would be a response that was completely unexpected in terms of how the Japanese and their Occupiers would interact.

By 1949, I was ship’s company on the USS Mount McKinley, and the Occupation had taken on a dynamic all its own. It was no longer about an armed force trying to sit atop a conquered population. It had achieved a certain symbiotic co-dependence, the whiff of which lingers even yet.

In order to better myself, I had been taking all the Criminal Investigation courses that the Marine Corps Institute had to offer by correspondence.

The awesome military machine that had overcome the Japanese militarists had withered away, and a few good men were needed to keep things going. With three weeks to go on my enlistment, the XO called me into his office and said “The people on the staff of Commander, Service Forces Pacific (SERVPAC) had looked at my record with favor.”

If I was willing to extend my enlistment, there was a job ashore for me, in Japan, doing what they called “Police Work.” I may have been young, but I was no fool. I knew about the Army Counter-intelligence Division (CID) and what they were doing, and I assumed I was being nominated for a Naval Intelligence assignment.

I agreed to take the job immediately. Two weeks later I was on a Naval Air Transportation Service flight in priority status across the Pacific. In the days of the four-engine prop plane, it took about five days to hop the vast ocean.

At Naval Forces Far East, I reported to the Force Intelligence Officer, CAPT Stone. He directed an organization that was not nearly so grand in scale as it had been in wartime a few years before. There were only five intelligence officers west of Hawaii, supported by an equal number of enlisted men.

The Captain got right to the point: “Navy has to clean up the black market mess in the Naval Zone of occupation south of Yokohama, or the Army will take it over. We can’t have that, and I need to get in there and clean things up. We are going to give you a squad of locals, and I expect you to show results. Quickly.”

He gestured over his desk and said I would be going down to Yokosuka to become Supervisor of Japanese Police, and would be empowered to handle any investigations required to do the job.

He said that my immediate reporting senior would be the area Provost Marshal, Colonel A. Bryan “Red” Lasswell, who was also Commander of the Marine Barracks.

The Captain leaned back and said that Lasswell was a legend in the business and had been in the Far East since Christ was a corporal- he enlisted in the Corps in ’25, was commissioned in ’29 and completed three years of language training in Tokyo in the mid-1930s in time to be assigned as Officer in Charge of the radio intercept station in Shanghai, before the three month siege that preceded its fall to the Japanese in 1937.

What I found out later would have amazed me then. The secrets of radio intelligence were still the most heavily kept of the war, and there was no relaxation in the peace that followed. A counterintelligence guy like myself had no “need to know.”

(Colonel Alva “Red” Lasswell. Photo USMC).

Red Lasswell was more than a tough Marine. He was one of the elite team who broke the Pacific War wide open. From Shanghai, he was sent to station CAST in the Philippines before being sent to join Joe Rochefort’s code-breakers at Pearl Harbor’s Fleet Radio Unit Pacific (FRUPAC). Jasper Holmes, one of the first to be permitted to tell the secrets, said that Lasswell had been the one to make the decrypt that enabled the Air Corps boys to shoot down Fleet Admiral Yamamoto in April of ’43 when he was traveling out to Ballale and Buin.

Of course, I knew none of that then. In a tone of dismissal, the Captain told me to “get some civilian clothes,” since rank had no place in this assignment. I would be dealing with corruption that knew no seniority, and deference to authority would only get in the way of the mission.

I was then directed to report to Colonel May, McArthur’s Provost Marshal, a tough old bird who made it very clear what I was to do. Those Americans who had been supervising the police were now in the brig for black marketing, and what’s more, most of the senior officers in the area were also making money on the side. He said that Army CID would be in contact, and that I was to work with them.

I was then sent to the Army CID Lab at Camp Zama for extensive instruction in the collection and preservation of evidence, and detailed procedures on working with Japanese Police.

It was a strange time still in Japan, and the scars of war were still raw. When the fighting ended in 1945, the US Navy took over the Imperial Japanese Navy base at Yokosuka, which had been the home of five carriers in its time. The big gray Japanese ships that had survived the war were long gone, dispatched like mighty IJN Nagato to the A-Bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in 1946.

As it became apparent that there would be no resistance to the Occupation, the Navy settled in to a new operating base in the heartland of the former enemy. The base bustled with activity, though the new occupants were confronted with enormous security problems.

The soft crumbly hills of Yokosuka base were honeycombed with tunnels burrowed to provide storage for critical supplies and protection from American air raids. Down in the warrens below were weapons and explosives and booby traps. Some of the first American explorers were injured, and more than one was killed.

There was rumored to be a full field hospital down below. There were tales that the air base in Atsugi was connected to the Naval base, and there were millions of rounds of ammunition stock-piled for the last great defense against the American landings.

The Navy was practical about it. First things first. Where there was a hole in the ground, concrete was poured, and all the tunnels were sealed; not only the ones on base but the ones that led to the Honcho-Ku neighborhood outside the fence.

The one cave that was preserved was the one next to the Headquarters Building. It had been the Command Center of the Imperial Japanese navy, and the new tenants liked to show it off. The Navy used it for another fifty years, and only moved out a couple years ago.

All the activity made the base a magnet for an impoverished civilian population. Japan had been stripped of all metal for war production, and now anything like copper or other base metals brought high prices on the black market. Japanese employees entering the base had lockers where they changed clothes, under police supervision, both entering and leaving. Copper and brass were literally as good as gold.

During the war all of the wood structures had burned in the fire raids. When peace came, they were rapidly rebuilt. One new home was erected directly over a tunnel entrance leading onto the base. The owner made good pocket change renting his private entrance to the gold mine.

A bulldozer and truck of cement solved that particular problem. That was just the start of it, though. Everywhere you turned around there was another hole in security, and it was hard to tell where the criminal blended into espionage. That is why it was so important to work with native Japanese, since getting information out of prisoners is a thorny question.

Maybe I should rephrase that. Getting accurate information is hard.

Even in America, the Police have always had their ways here in America, and the sweat-session and occasional beating is the very essence of the Sam Spade-style detective novel. The problem with that sort of approach is that often the information that is produced is bogus, and manufactured just to get the pain to stop.

The American POWs who were so badly tortured in the prisons of North Vietnam spun incredible tales to try to satisfy their captors. There were interrogation notes that featured diagrams of the live-stock pens, swimming pools and bowling alleys on the aircraft carriers that operated off the coast.

When the truth became known to the Northerners, that their brutal sessions had only produced fantasy, the consequences for the prisoners were dire.

That is one of the surreal aspects about the controversy over the water-board procedure tactic, and whether the CIA should be permitted to utilize it in a small number of cases. It was introduced into the American training syllabus for survival, evasion and resistance school just to give a taste of how bad things could be in the hands of the enemy.

There was a time when the argument would never have occurred to anyone.

When WW II ended, the US Navy ships at the former Imperial Navy Base at Yokosuka off-loaded all the ammunition and stores they could in order to make space for troops to ride the ships back to America in the great demobilization.

There was a lot of stuff to get rid of. Plans for the invasion of the Home Islands, code-named “Operation Olympic,” had called for massive amounts of materiel to be on hand in the Far East for a protracted and bloody struggle.

Every Purple Heart Medal for wounds in action awarded since 1945 comes from the stock that was created just for that campaign. Say what you will about the horror of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the mute evidence of those awards is enough for me.

Meanwhile, I was on my way to clean up the zone of naval occupation south of Yokohama. Corruption was rife, and the Army was threatening to take jurisdiction if the situation was not improved. McArthur’s General Headquarters was not happy.

When I completed my hurry-up orientation with Army CID I caught a train south from Camp Zama to take up my duties, which was to the language and cultural skills of our host nationals to bust up the black market in the Honcho-ku neighborhood outside Yokosuka Base and sever the cords that tied it to things inside the base perimeter.

I will tell you more about that tomorrow. I have all the time in the world, now.”

Copyright 2013 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.comRenee Lasche Colorado springs