Bikini Bound

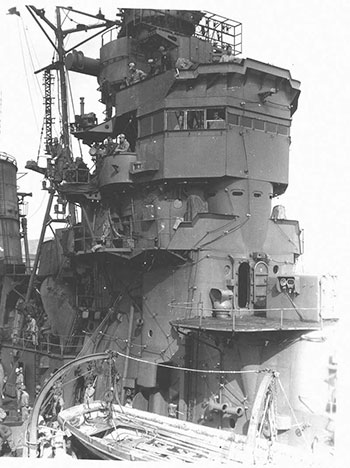

(ex-IJN Nagato prepares to get underway in Yokosuka, March, 1946. Alongside is the tank lighter the battleship used for logistic support from the shore. Colorized Photo USN).

We sailed from Yokosuka on 18 March, 1946, amid rain squalls. We slipped down the Sagami-wan navigating by time and compass with the cruiser Sakawa on in company on our port quarter. “Well begun, half done,” I said to Captain Whipple as he gazed at the rain from the Pagoda’s nav bridge. He grimaced and said he sure as hell hoped so.

The evening meal was good and movies were shown. Everyone was in high spirits. Nothing happened during the night and by morning we were clear of the land. It was a cloudy day with a gale on our port beam, but already the wind and water were warmer. We settled down into the pleasant routine of life at sea.

Water was getting in through cracks and leaks everywhere, but we managed to keep ahead of it. The crew was tired but confident.

On the third day out, the wind was still abeam with rough seas, but the water was definitely bluer. It was then that we got the first hint that adventure might be in store for us.

Sakawa signaled she was making turns for fourteen knots and wondered how long she would have to keep it up. This was puzzling as we were only making ten knots, yet the two ships stayed right together. The water did seem to be slipping by pretty fast, at that. I hoped she was right. But presently the sun appeared; we shot it and it worked out. Ten knots was right.

Another message from Sakawa: “Fuel consumption was fantastically high, there were not enough men to man the fire rooms.” In short: could she slow down to eight of her kind of knots?

Captain Whipple directed the signal back: “Negative. Sakawa is junior ship and will maintain position in formation.” It was ten knots through that night and the following day.

The morning of the fifth day found us in the trades with mounting deep blue seas, clear sky and wind from dead ahead. We were taking on too much water. The patch put by the Japanese on the bomb-hole in our bow was working loose and we were down a little by the head. Several pumps had failed and our electric system was in trouble as salt water reached point after hot point, shorting them out. The crew was very tired, but the thought of doing better than Sakawa buoyed them up.

Finally, though, the cruiser’s incessant pleas that she could not continue at that speed began to hold sway. Her Captain claimed she would be out of fuel in a few more days, and thus Captain Whipple reluctantly directed us to slow to eight knots. The reduction hurt the fuel efficiency of the battleship and made her increasingly difficult to steer, her bow wandering constantly across the blue horizon.

To get the rudders deeper in the water we had to flood compartments aft. I estimated that the forward compartments held about 150 tons of sea water; therefore, to balance the ship for efficient speed, it was necessary to take 260 tons of water into the stern compartments. This caused a tremor of anxiety to flow through the crew, who understood full well, despite all the sophistry of the naval vocabulary, what “loss of buoyancy” meant. Water foamed in over the seacocks. We began to bail.

Morale of the crew rose again the next day as we prepared to take Sakawa in tow when she actually ran out of fuel. Now, they would show those people who had the better ship!

(Bridge of ex-IJN Sakawa, 1946. Photo USN.)

The towing wire was too heavy for our small deck force to handle in the usual way. We could call on the larger force of engineers when absolutely necessary, but only for short periods since they had boilers to tend. We took a couple turns of towing wire around the number four turret and led it aft to a pelican hook for quick release should anything go wrong. Then we cut through the port towing hook, dragging it forward. It was tough, dirty work, keeping the weight always on the deck. We hung loops over the side and made them fast with light hemp lines.

The idea was that Sakawa would pull the towing wire off us gradually, breaking the hemp lines one by one, as a man might pull an adhesive plaster off his chest. Working up to a position amidships on the port side we lashed down a bight and carried the wire aft again the same way but with different hemp lines, then around the stern and forward on the starboard side nearly to the bow. From the end of the wire we continued with six hundred feet of eight-inch hawser, lashing it in place the same way, and continued that with three-inch and finally one-inch line terminating in a float.

The plan was that we would float the small line back to Sakawa; then we would haul the three-inch and the eight-inch lines in as we cut away the hemp lines—then the cruiser would take a strain on the eight-inch with her winch, and pull the eye of the towing wire over and make flat to it, and then pull off the full length of the towing wire.

Hairless Joe the Bo’sun would follow along with a fire axe, just in case anything got stuck.

It didn’t work that way the first time, but Sakawa managed to raise steam and we proceeded south, making best speed possible. We had no idea how much fuel we had, or what tanks actually contained sea-water instead of oil. This was something quite unlike anything I had ever seen at sea, and we were not even half way to the Marshall Islands.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303