Captain of Company H

Two weeks later I was on my way to Nashville with another gang of government workmen. I felt much better than I looked, due to the ravages of the Pox. At Edgefield Junction, Mike Costalo came through the train, apparently looking for some one. When he got near me, I spoke to him. He said: “Your voice is familiar, but I do not know your face.” I told him who I was, and explained that I had just passed through an illness not conducive to beauty, but that I was still in the ring and ready to spar.

He motioned to me to follow him, and we went out on the platform, where he informed me that he had come out to the Junction to warn me that a government detective, James O’Donnell, was at that very moment waiting for me in the depot at Nashville. He had come to tell me because I had been kind to him while he was in a Confederate prison. He had a hansom rig in waiting for me on Market Street; so when we reached Nashville, we got off on Front Street and hurried over to Market Street and into the hack. He took me to his home in North Nashville. I remained there until the next night, and then I went to the Franklin shops on Spruce Street. These shops were operated by the United States government, and a friend of mine, Tobie Burke, was in charge.

He had a nice room fitted up in the second story, where I could sleep all day. My nights were devoted to tramping. My youngest brother was employed at these shops, and I made him take me around to all the Yankee headquarters to see what intelligence about the invaders I might glean. I got acquainted with a number of the officers, and was offered a position at a salary of a hundred dollars per month by the provost marshal. I accepted the offer, telling him I would be around to set in working within the next week.

I went to see my Colonel’s mother during my visit. Mrs. Louisa McGavock was a grand woman. I do not think she ever forgot a kindness or remembered an injury. Her interest in and her devotion to Col. McGavock’s old company, the “Sons of Erin,” never ceased. The friendship between us that had its beginning in the grave at Raymond lasted until she was placed in the vault with her son at Mount Olivet cemetery in Nashville.

The first baby girl born in the house I made with my own hands in Nashville is her name-sake, and her name will be spoken with love and respect as long as the house of Griffin exists.

I also visited Tom Parrel, who had a son in my regiment. He told me he had taken the oath of allegiance, but that his wife was still a genuine Rebel. Mrs. Parrel wanted to give me a roll of greenbacks, but I told her I had all the money I needed. After I left her house, I found the same roll of money in my pocket. She was as gererous as the day is long, and I bless her memory.

I called on Mr. K— and told him about his son, Captain James K— being wounded at Raymond. He was not disposed to be friendly, so I cut my visit short and went over to Captain Stockell’s. His son Charlie was a Captain in the “Tinth.” He was delighted to see me, and wanted me to come and stay at his house while I remained in Nashville. The last call I made was at the residence of Captain George Diggons’s father; but when I got there, Mr. Diggons was dying. I went again the next day, and was there when he died.

There was a government office across the street from the Diggon’s home, and while I sat there I saw a number of Yankees coming and going on horseback, and came to the conclusion that it would be a good place to capture a horse and get away. I waited there again, and took my place at one of the front windows the next day. I was a fairly good judge of horseflesh. Soon a fellow came riding up on a black horse. I knew that was the animal for me, so by the time be was sitting down at his desk I was on his horse and making my way toward St Cecilia Academy.

The girl with the auburn hair was there, and I decided right then: I would like to go and see her while I was in the neighborhood. The chances were not very bright when it came to ever seeing her again. As it turns out, I did indeed see her sunny smile and laughing Irish eyes again, but life in wartime is a chaotic thing and you have to take your chances when you have them.

While I sat there talking to her in a shady spot in the garden two Yankee officers came riding by. She is a brave woman, my comrades, but she was certainly scared that day. I told her not to mind them, for I could go around Yankees like a hoop around a barrel. They did not stop to ask any questions. I assure you we both felt easier when they were out of sight and in a little while I bade the lovely girl good-by, asking her to remember me in the fight to come. I tipped my hat, mounted my proud mount and crossed the river, striking out toward the Springfield Pike. I did not stop again until I reached Cedar Hill.

While there, I made my headquarters at Squire Jack Batt’s, two-and-a-half miles from town. I had spent my childhood there, up until Father died while laying track on the railroad and knew the country well. Two or three companies of the Third Tennessee had been raised in this neighborhood, and everybody wanted to give me a welcome.

I had lots of callers; every mother, wife, sister, and sweet-heart wanted to send something to loved ones in the army, and I could not have taken all the things they brought me if I had had a two-horse wagon. With the help of some of the boys and girls, the socks, underclothing, etc., were made into a long bundle, and with sundry letters and sacks of tobacco sewed into my saddle blanket. I had letters by the hundreds and sacks of tobacco by the dozen. When I left there to start on my long journey, several of the boys and girls accompanied me as far as the Cumberland River. They saw me safe on the other side, and watched me until I rounded a bend in the road and was sundered from view.

The first night I was out I slept on the porch of a farmer’s house, with my saddlebags for a pillow and my saddle blanket for a bed. I had two Colt’s six-shooters. My horse was hitched to a post near me, and a piece of rope that I had fastened to the bridle was under my head. My bundles were all fastened to my arm, so that if any one disturbed them I would wake up.

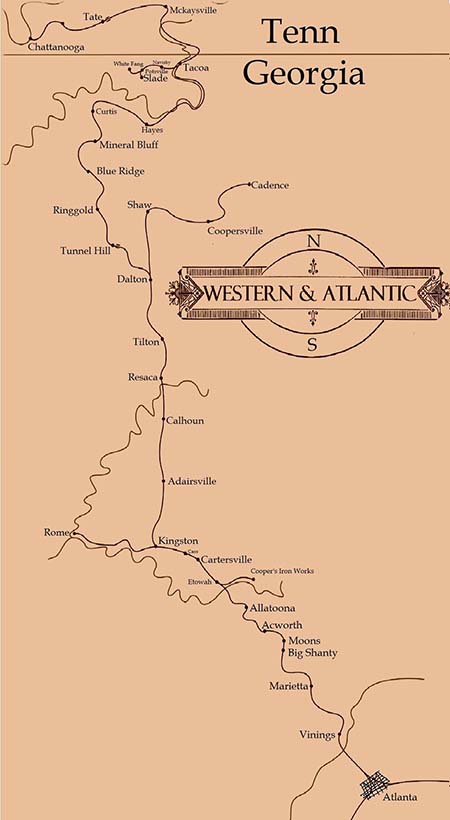

I will not relate the things that happened to me on the rest of the way to the Army of the Tennessee. I followed the line of the Western & Atlantic railway, since the grade suited my horse and I kept a sharp eye for highwaymen, riff-raff and deserters. The woods were alive with men who should have been elsewhere. I crossed the Tennessee River above Florence, went over the great Sand Mountain Plateau in northeastern Alabama, and saw the Black Warrior River. That placid stream was named after the Paramount Chief of the Tuskaloosa Indians, and preserved the memory of that tribe after their expulsion west.

(Map of the Western & Atlantic Railroad. Courtesy Eddie Sand).

Eventually, I caught site of the evidence that a large company of soldiers had passed this way not long ahead of me- rails were missing from fences and houses had been knocked down for firewood. As I approached the main body of the Army of Tennessee, I was challenged by pickets. I told them truthfully I was a Son of Erin who had fought at Raymond and was returning to my unit. They let me pass, and when I found the boys, I was minus many articles of wearing apparel and several sacks of tobacco that had aided my passage. But I had the letters from home for the lads and they were all safe and sound. I think there must have been between three or four hundred missives, and can say that was the best mail call Company H had in the war.

I presented the Yankee horse to Maj. John O’Neal, of my regiment. At least, I only took his note for the two hundred and fifty dollars he agreed to pay me for the animal. It might have been the letters I brought, and the stories I had to tell them all about my inadvertent furlough. There was a great deal of uncertainty in the Army of the Tennessee. Company H of the Tenth had been in Bushrod Johnson’s Division at Chickamauga, and done well, capturing a Federal artillery battery of nine guns. But the number of us who had signed up at the start of the war were dwindling. In order to make up an effective brigade, we were combined briefly in Walker’s Division, and then wound up in Bate’s Brigade of John Breckenridge’s Division.

That is pretty much the way the formal organization remained until the Battle of Peacehtree Creek. Promotions, death and wounds had left a vacancy in the officer ranks of the company. You could have knocked me over with a feather when the boys elected me Captain of Company H, the Sons of Erin, and their last one.

When we marched off in Nashville beyond Captain McGavock in 1861, I never could have imagined that God’s Own Gentleman would be in his grave, and I would be in his position less than three years later.

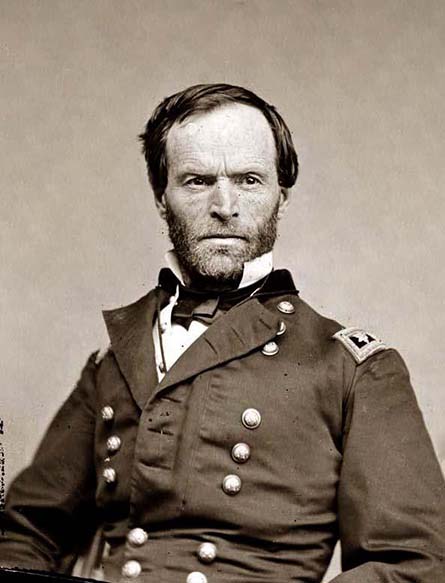

(William Tecumseh Sherman. Image Library of Congress).

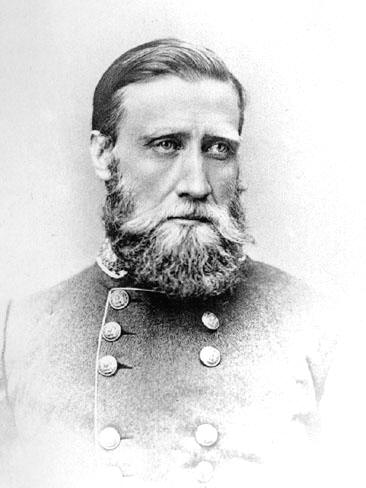

But there was much sadness to come as we confronted hard-eyed Tecumseh Sherman in Georgia. By December of 1863, our brigade seemed to have as many units as there were men left in them. Ours consisted of the 37th Georgia Regiment, the 4th Georgia Battalion and five of combined formations of our sturdy Irish Tennesseans. Still to come was the general engagement at Missionary Ridge and the retreat to Atlanta. The events of those days were ones that pain me to this very day, but I did have the opportunity to serve directly for one of the great generals of South, the indomitable John Bell Hood, of Texas.

(A mournful John Bell Hood of Texas).

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303