Cass Corridor

(1973 GMC Chevy Vega Kammback Wagon. Photo Socotra.)

I can’t talk about the creation of the fabulous ruins of Detroit without mentioning the ride I had at the time. Raven bought it, brand new, and gave it to me to ensure that I had reliable transportation to get to work. It was part of the civil contract we had between the generations to transition me from dependent to working citizen.

It was the model for the contract I had with my boys, and hope that they, in turn, can carry it off for their kids, should they ever get around to having any.

I had to think about that when I was signing the title for the Bluesmobile over my younger boy on Saturday. It was a strange enough day as it was. The Title was crisp from my files. My son needed it because he couldn’t stand the vanity plates on the car that feature the big block “M” of my alma mater.

He is a proud Spartan, and was incensed at the idea that people might mistake him as a Wolverine as he thunders around the Beach town in the Police Interceptor.

One thing led to another as he sought to replace the tags with something more neutral. We finally agreed on the “Fight Terrorism” logo for the new plates, which is rational enough, since that is the business I retired from and the one he is going into.

Unfortunately, the Commonwealth insists that his name appear on the pink slip in order to do so. That is why I inked in “$1” in the “price sold” block and signed the car over to him. The Virginia pink slip is green, of course, the color of my 1973 Vega.

I still think fondly of that car. It was a piece of crap, of course, from the great age of Detroit rolling pieces of crap. 1973 might have been the peak year for lousy quality control and UAW workers with attitude. Remember? We used to say we didn’t want a Monday or a Friday car, which was to say, the work-force was notoriously careless in the assembly process coming back to work after a hard weekend, or getting ready to party on the weekend.

The Vegas were thrown together at the plant at Lordstown, in Eastern Ohio. I see the plant every time I drive up to Michigan, but it is far enough away that I could not get down there to see them put the Kammback Wagon together, or know precisely what day they hammered it together.

I still think it was a good-looking car. ’73 was the last year the Feds did not require those ugly rubber energy absorbing bumpers, which were ugly as sin and didn’t really catch up with the rest of the design for years. The mini-wagon design flowed nicely and gave a lot of room to throw stuff in the back, sleeping bags and old liquor boxes filled with LPs and college textbooks for the job.

The 1973 Vega model year featured over 300 changes, including new exterior and interior colors and new standard interior trim. I ordered the tan interior and British racing green for the exterior paint. The four-speed manual shifter was from Saginaw Steering Gear, and a new shift linkage replaced the Opel-built units. The L-11 engine featured a new Holley staged two-barrel carburetor.

I specified the BR70-13 white-stripe steel belted radial tires for the Kammback Wagon, and thought I was pretty cool rolling down Woodward or the Cass Corridor in my little car. It was quite a change from the muscle beasts we learned to drive in. Small was beautiful in the days of the even-odd gas lines, a thoroughly un-American restriction on our traditional ability to drive anywhere at any time.

Much as I liked it, the Vega was a piece of crap. It burned half a quart of oil for every tank of gas, just like clockwork. It was not shoddy workmanship, though, it was that the Vega engine was not ready for prime time, which was true of the whole industry that year.

GM Research Labs had been working on a sleeveless aluminum block since the late ’50s. The incentive was cost. Engineering out the four-cylinder block liners would save $8 per unit. Reynolds Metal Co. developed a custom alloy suitable for faster production die-casting.

The Sealed Power Corp. developed chrome-plated piston rings specially blunted to prevent scuffing. It might have been a successful design, with a little more time for development, but the OPEC embargo prevented that. Demand for fuel efficiency was suddenly really important and the engine was rushed into production.

Who could have imagined that V-8 powered Detroit would suddenly have an immediate and pressing need for four cylinder engines?

I tried driving 55 on I-75 the morning after President Nixon announced how important it was that we conserve energy. I was nearly run over by a Buick hurtling toward the Livernois exit. I was so young that I took things the President said seriously.

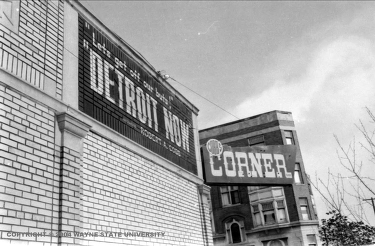

(Cass Corridor landscape. Photo Detroit news.)

After that, I preferred to motor more sedately down Cass when I visited the Wayne State University campus. Cass Avenue runs parallel to Woodward, which is the golden road out to where white Detroit was fleeing, out toward Grabbingham and Bloomfield Hills and the mansions of the car people. Cass runs from Congress Street, ending a few miles further north at West Grand Boulevard.

(Detroit’s famed Masonic temple. Photo Wikipedia.)

Significant landmarks along the fourteen blocks that constituted the Corridor included the Detroit Masonic Temple, which looks like a church but is actually the world’s largest building of its kind, and Cass Technical High School and the small but densely-packed Chinatown. The architecture was 1930s-industrial, for the most part, and low apartment buildings and tons of bars and restaurants.

(Cass Tech High School’s old building.)

The area was populated mostly by white southerners and their successors, who had come north during the war. There were Hindus and Native Americans, burned-out hippies, students from Wayne State and single-moms struggling to raise their kids.

Immigrants from India, Pakistan, China, Korea and the Philippines were part of the mix. Many worked at the Detroit Medical Center, a group of hospitals just across Woodward Avenue.

Detroit’s small Chinatown was located at Cass and Peterboro in the southern end of the Corridor, and there was often a wait for tables at lunch.

That was during the day. The proximity of Cass to Woodward, Detroit’s main artery, had made Cass the logical area for the local authorities to push local drug activity, prostitution, and general civic indecencies away from the downtown.

Long-legged, high-heeled hookers, predominantly white, prowled the sidewalks outside world-class dive bars like Jumbos, The Sweetheart, Willis Show Bar and Anderson’s Gardens. The Gold Dollar Show Bar advertised “Female Impersonators Nightly.”

Crazy was OK. Prime-time sidewalk shows featured the working ladies who would flash their breasts at the Johns driving in from the suburbs, their pimps, winos, scammers, dopers and dealers.

The bars- particularly Anderson’s and the Wills, were all paying for active police protection, and despite the seedy nature of the neighborhood, I never felt bad about going down and hanging out. I used to love to take visiting Book Company people to Anderson’s Gardens. It gave them a thrill, but I knew the place was 100% safe.

At least it was then. As inauguration day rolled around for Coleman, and as Dick Nixon lurched through the last anguished days of his presidency, things were about to take a dramatic change, courtesy of the scourge of crack cocaine. But I will have to get to that tomorrow. Here is a taste of what is to come:

“In a very real sense, the mayor of Detroit and the Detroit media serve different constituencies. The media seem never to have recognized that. The reporters talk about Detroit as a large metropolitan area spreading far from the city center. Coleman wasn’t elected by those people. In the view of the Mayor, the media represent an outside set of interests-interests which should be treated with suspicion. Given the social geography of the metropolitan area, there is a racist relationship between the media and the city.” Wilbur Rich, in “Coleman A. Young and Detroit Politics”

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com