Coast to Coast

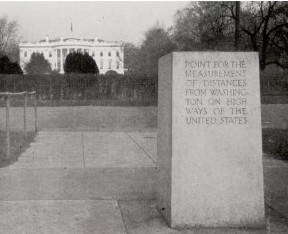

(Milestone Zero, Route 50, Washington, DC. Photo US Army)

I had intended to be further along on about ten things today, and the story is getting out the door later and later. It is OK, though. Car Week is over in Monterey, The Dream Cruise is about to begin on Woodward Avenue, and the placid fields of Indiana are calling. A century ago the idea of hopping in the car to drive to a destination a few states away would be unthinkable, but now, it is almost literally, a piece of cake.

This particular cake will be the color of the cement on the greatest construction feat of humankind, something bigger than the Great Wall of China, something to dwarf the Pyramids. A monument so massive it can be seen from space, and the remains of which will last as long as the continents.

I am completely confident that Ike Eisenhower would agree with my priorities, since he was a man who liked his challenges.

We have talked a lot about our crazy love affair with the carburetor- now the fuel injector, but all that would be for naught without our freeways and turnpikes and those annoying State Patrol ambush sites all along the way.

You would have to start with the visionaries who organized the movement to promote The Lincoln Highway, a bold vision of a paved road all the way from New York to San Francisco.

Imagine what the country looked like then. In 1912, the great 19th century marvel of the intercontinental railroad dominated inter-state transportation. Roadways were primarily things of local interest. Outside the metropolitan areas, “market roads” were maintained by counties or townships, but there was no state bureaucracy to maintain an integrated network.

Maintenance of most rural roads was the responsibility of those who lived along them, which is to say that the entire country had signs announcing “State Maintenance Ends.” In fact, many states had constitutional prohibitions against funding basic infrastructure such as road projects, and federal highway programs were not to become effective until 1921, due to the publicity raised by a spectacular Army project.

Let’s take a look at what things were like as the new motorcars began to change America. At the turn of the century, the country had about 2.2 million miles of rural roads, of which less than 9% had “improved” surfaces: gravel, stone, sand-clay, brick, shells, oiled earth. The rest were dirt. Inter-state roads were considered a luxury, something only for wealthy travelers who could spend weeks riding around in their automobiles.

The New York Times called for a system of improved interstate roads in an article in 1911, just as the diggers were completing the biggest public works effort in human history at the Panama Canal. It was the American Century, for sure, and the Nation could achieve anything.

President Robert P. Hooper of the American Automobile Association and Speaker of the House Champ Clark thought that the time had come for the “general Government to actively and powerfully co-operate with the States in building a great system of public highways…that would bring its benefits to every citizen in the country.” However, Congress as a whole was not nearly as progressive as it is now. Most of it felt the idea of a national network or highways was just too expensive.

Why, you might as well want to go to the Moon, you know?

But think back. Way back. In the summer of 1919, the young Lieutenant Colonel Ike was just back from France, and he jumped at the chance to join the first Army motor convoy across the country.

It was an impressive stunt, and one that was direly needed by the War Department, headquartered in the massive Munitions Building next to the Reflecting Pool on the National Mall.

With the War to End Wars just concluded, America at that moment was not sure that it needed much of a standing army, and a demonstration of capability had to be a good thing when the Armed Services Committee met on the Hill to consider the Army’s future budgets.

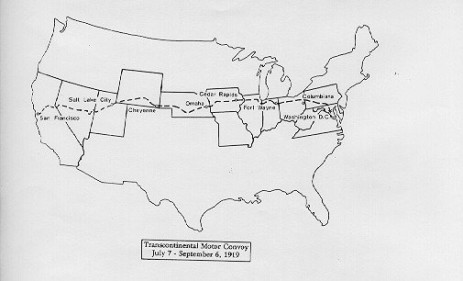

The Army devised an idea of dispatching a column of vehicles from coast to coast, from the reflecting pool in Washington all the way to the Presidio in San Francisco. The idea was a thoroughly Army sort of thing: it would feature a convoy of eighty-one motorized Army vehicles. The convoy would cover a distance of 3,251 miles in just over two months. A speech about progress and the national defense need for Good Roads would to be made at each stop, which was at least as important as the trip itself.

Ike hated that part of it, and when he finally got a chance to control when and where the speeches were made, he kept them short and business-like.

The last time I crossed the country by car, sixty-five years later, the trip from ocean to ocean took not quite four days. I was not pushing it and no one was particularly interested in what I said when I periodically emerged from my 1990 Dodge Shadow four-banger turbo.

Not true back in the day. The Convoy left the Zero Milestone in Washington, DC, and headed north and west through Arlington to cross the Potomac near the Point of Rocks, the place where the Confederate armies had passed north into Maryland on their way from Culpeper to Gettysburg to the High Watermark of the Lost Cause.

Young Ike Eisenhower joined the convoy in Frederick, Maryland, on the night of the first encampment. He was along mostly for the adventure, since the expedition was a demonstration of the phenomena that career military officers know well. The war was over, there was excess capacity in the force, and there was a clear and present need to preserve resources that had to be avoided at all costs.

The transcontinental convoy was something that still resonates because of the profound way it affected the nation, and saving the Standing Army. Lt. Col. Eisenhower learned first-hand of the difficulties faced in traveling great distances on roads that were seasonably impassable, and not much improved most places from the days of the wagon trains.

Lt Col Charles W. McClure and Capt Bernard H. McMahon were the respective expedition and train commanders[ of the expedition, and of course there was a train to carry spares- this was the Army Green Machine, after all. Civilian Henry C. Ostermann of the Lincoln Highway Association was the guide- there was no standard system of road signs in those days, and in many ways the expedition was relying on compass and motorcycle scouts for navigation..

It was a major production number. The Signal Corps documented everything on film, there was a band, and the Public Affairs Officer rode a week in front of thee main body, followed by the recruiter and the chow hall workers.

Two motorcycles scouted about a half hour ahead to report conditions and place markers for the Field Artillery 5 ½ ton Mack trucks, which were in turn followed by a mobile machine shop and a unit of the Quartermaster Corps bringing up the rear.

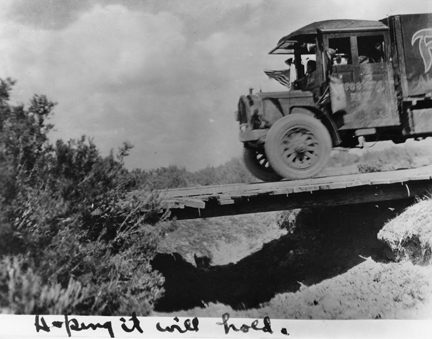

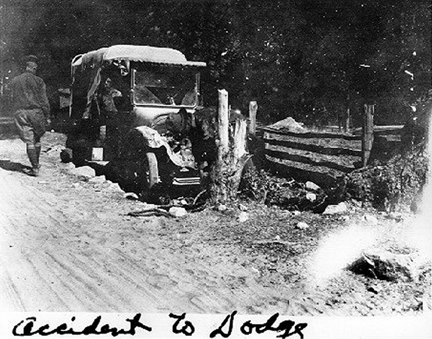

It was the Wild West, literally. There were 230 road incidents, which included stops for adjustments, extrications, breakdowns and accidents. The 81 vehicles in the Convoy and trailers included “34 heavy cargo trucks, 4 light delivery trucks”, three mobile machine and blacksmith shops, a wrecking truck, and the “Artillery Wheeled Tractor.”

Nine trucks did not complete the route, but the great automakers of the day all got a chance to showcase their wares: Liberty and Mack trucks were lead by Cadillac, Dodge, Garford, Packard, Riker, Standardized, Trailmobile, and White all rolled on Firestone tires. Harley-Davidson, Indian provided the scout bikes).

Dealers en route supplied gasoline and tires out of patriotism and for advertising. It was both a spectacle and spectacular. By the time the column passed out of the Land of Lincoln, virtually all the roads were dirt. The Convoy broke 14 bridges in Wyoming, and soldiers repaired them.

The convoy travelled at breakneck speeds up to 32 mph, and intended to average 15 mph speed of advance. The reality was not nearly so good. With delays and repairs, the actual trip across 3,250 miles required 573.5 hours and averaged only 5.65 mph over the 56 days. The Average travel day was ten and a half hours.

They stopped for six rest days, at East Palestine, OH, Chicago Heights, IL, Denison, IA, North Platt, NE, Laramie, WY and Carson City, NV. The mud, tough terrain and inadequate bridges held them up, and the convoy did not demonstrate the crisp military adherence to schedule. Falling nearly a week behind, they skipped a last rest day at Oakland, CA, and took the ferry across the bay to park in triumph, finally, at the old Spanish fortification of the Presidio in San Francisco.

The path had been conquered, coast-to-coast, and the nation followed the Army’s progress with breathless interest. It did not save the budget, per se, but it did spur interest in a national network of roads for smooth transit from coast to coast.

One of the matter-of-fact lessons the future General of the Armies learned was that the nation needed a good and uniform system of roads, and that a high-speed network of them was not only a matter of safety and commerce, but a matter of national security.

It was the beginning of something so profound as to defy easy description. With the good roads movement, the development of the auto and the byways on which it was appearing in increasing numbers gained momentum. A commission in 1926 designated names for all federal highways in the forty-eight states. Highways going east to west were given even numbers, and highways going north and south were given odd numbers. Major coast-to-coast highways were assigned numbers ending with zero.

The road that ran out of DC was called Route 50, and The National Boulevard got a number to go with its name.

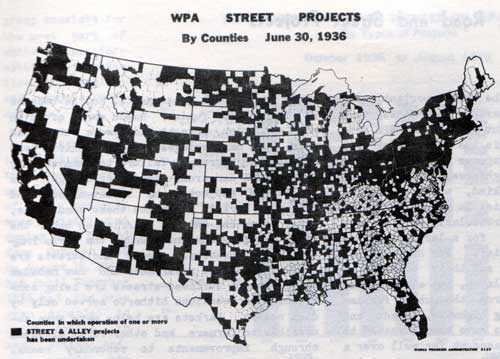

The Depression-era Works Progress Administration provided “shovel ready” road projects through the tough times, under the rubric “Farm to Market” work across the country.

(Depression-era Works Progress Administration road works by county. Photo WPA).

World War II and victory over Germany and Japan opened the floodgates on consumer demand for automobiles and new tract housing and new roads to carry them.

Ike assumed the Presidency in 1952. He remembered his trip thirty-odd years before vividly- in retirement he devoted a whole chapter titled “Through Darkest America With Truck and Tank” in his 1967 book At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends. His exposure to the autobahn network in Germany combined a profound understanding of both the need and the solution. In 1954, he announced his “Grand Plan” for highways.

On June 29th, 1956, he signed the Interstate Highway Act, which was effectively going to kill the downtown district of every big city. It was OK. America was becoming a place where everyone could aspire to have a couple of automobiles.

The miracle of the superhighway: The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways. What a way to roll.

Copyright 2007 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303