Damage Assessment

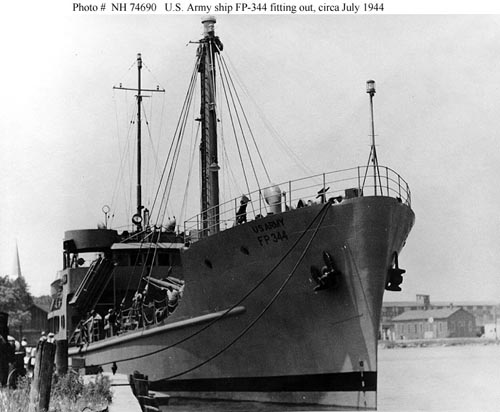

(USS Pueblo, TAEG-2 as she appeared when commissioned in 1944. US Army Photo.)

I always get a little unhinged in time when I hang out with Admiral Mac. His merry eyes dance across the decades, sweeping me out of this bold new decade in a slightly threadbare almost post-American century.

We are hanging in, but barely, and at some point the music is going to stop and we will look around as the lights come up and the nightclub is going to look as seedy as old Detroit. I have tired to be kind to my old hometown, tough a little fascinated by what has occurred to a once vibrant place, and if you want to take the extended tale as a metaphor for what happens when you stop paying your bills, personal or civic, that is entirely up to you.

Anyway, I asked Mac about his last big job in the Navy.

“I retired in December of 1971,” he said firmly. “I was Chief of Staff of the Defense Intelligence Agency. In those days they had a firm rule about having the three major military departments represented in the leadership. Army had the Director, an Air Force officer was the Deputy position and I was the two-star CoS for Navy.”

“That was after the damage assessment on the capture of the USS Pueblo? That must have been fascinating.”

“And grim,” said Mac.

I looked at my notebook to see where I might insert the notes. I had jotted down the series of discussions about the legendary Marty Hurwitz, who I knew as the all-powerful director of the General Defense Intelligence Program, and whose job, in one of those accidents of history, I had in a much later incarnation.

“We talked about Marty last fall. What was the story, again?”

“Marty was an Army officer who came to work for me as Director of Plans. He had been in Germany, and the service has ordered him in to relieve the desk officer responsible for Israel.”

“So how did he get to you in the budget shop?” I asked, marveling that Mac and I shared the arcane art of the DIA budget program thirty years apart.

“The leadership saw his name and couldn’t tell if he was Jewish, and when they asked, the Army said it was none of our business. So they changed the orders and put him in charge of the Planning, Programming and Budget system. He got out of the service and stayed there for 25 years.”

“I remember,” I said. “Everyone was afraid of him except Lew Prombane, the Comptroller. I worked with him after I retired. They were Titans, I’ll tell you.”

Mac laughed. “They were just a couple kids, Lew was coming from a junior Navy job and Marty was still wearing railroad tracks. But then the North Koreans seized the Pueblo and I had a new job and a really important one, since Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms was intensely interested in what had been compromised in the capture.”

“That was in January of 1968, right? I told my buddy the Lawyer we would be talking about it and he said he had a picture of Pueblo in his USS Princeton cruise book, taken in December of 1967 before she got underway for the Sea of Japan. It is maybe the last picture of her taken while still in American hands. He scanned it and sent it to me.” I pulled it out of my notebooks and passed it over.

(Last picture of USS Pueblo (extreme left) with an American Crew, December, 1967. Photo courtesy SerraLaw.)

“I have seen more pictures of that ship than I ever need to,” said Mac. “We actually recreated the ship to figure out what had gone missing on us, and it was a lot.”

(KW-7 Crypto machine similar to the one on USS Pueblo, TAEG-2. Photo National Cryptlogic Museum.)

“Do you think the Soviets egged the Koreans on to get the crypto gear on board?” I asked. “ The KW-7 encyphering equipment, paired with the codes that jerk Walker was giving them, would have permitted the Russians to read all the secret-level message traffic. Vietnam was at its height, which is why John Walker should have been hung.”

“Yes, and I think, Yes.” Mac took a sip of his drink. “There were a lot of strange coincidences in 1968.”

“There is even a Detroit angle,” I said with a note of triumph. Mac looked at me skeptically.

“1944,” I said. “Pueblo was built at the Kewaunee Shipbuilding and Engineering Company in Wisconsin as an Army logistics ship. To get out of the Great Lakes she would have had to steam through Mackinaw to Lake Huron, down the east coast of Michigan, and then through Lake Saint Claire through the Detroit River. Maybe she made a port call there and the crew went ashore and got liberty in the Motor City while it was humming, and the war plants were operating around the clock.”

Mac smiled. “She was commissioned in New Orleans, so my guess is that she came south to Chicago, then passed through the Chicago Sanitary and Ship channel to the Mississippi.”

“Dammit, there is Chicago again, stealing Detroit’s glory.”

“I got commissioned in Chicago,” said Mac, “When Rush Street was still off limits to navy personnel. That is one hell of a city.”

“I know,” I said wistfully. “It is still alive.”

“But do you want to hear about the damage assessment? If you do, we have to talk about the armed merchant ship General Sherman, and the battle flag of Korean General Uh Je-yeon, and then how the Pueblo got from Wonsan on the East Coast to Pyongyange on the West.”

“Do the north Koreans have a shipping channel I don’t know about? They couldn’t have got her underway again, could they?” I asked with a smile.

Mac just smiled right back and I opened the notebook to a new page.

(People’s Museum #5 in Pyongyang.)

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com