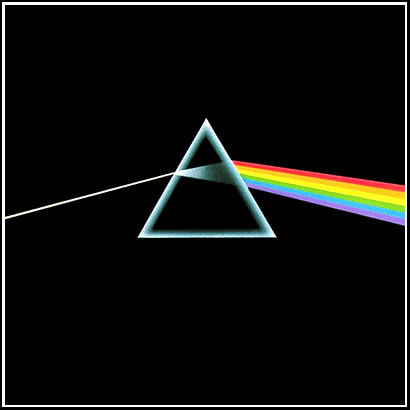

Dark Side of the Moon

(The enigmatic cover of Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon.)

I threatened you that I was going to take you back to 1973. Fasten your seatbelt and turn up the iPod.

You have to put tunes to the year, that is the way it was. The Allman Brothers might have peaked that year, and Elvis might have made the first global concert a reality in his appearance in Hawaii, but the real deal was Pink Floyd, the elliptical English underground band that released “Dark Side of the Moon.” The album that stayed on the Billboard charts for a mind-boggling fifteen and a half years.

The Vietnam War, The Nixon Presidency, Jimmy Carter and the Reagan Revolution would all pass before the album fell off the charts. Of the class of ’73, Only Coleman Young outlasted the album.

That year was a tipping point in the history of the Motor City, and it was a privilege to be there for it, since I was part of the class of ’73, too. In that year, the Motor City demographics were at an uneasy balance. There was a scant majorty of white residents- 52%- with African Americans composing 44% and Latinos a bit less than 2% and the remainder a small but growing Middle Eastern community. Mayor Roman Gribbs presided, but he was a caretaker for the legacy of poor Jerry Cavenaugh, who took the rap for bungling the handling of the riots.

(The last- and only- Polish Mayor of Detroit, Roman Gribbs.)

Gribbs was determined not to stay on, not liking what he saw coming for the City, and that is just when I walked into the movie. There was going to be an election, a show-down between law and order and an entirely new order.

Just a little bit late. I had to finish up a couple credits in the first half of the bisected summer trimester term, and was just about ready to get out of a suddenly sleepy Ann Arbor in June. I cut my hair off and looked for work, and was surprised to find a job with the college textbook division of the massive McGraw-Hill publishing empire.

It was an unsettled time, just as Pink Floyd’s album talked of he madness in the air. I had a draft number that a couple years earlier would have had me casting about for a way to avoid being a rifleman in the war, but the last combat troops had been pulled out of Indochina in March of that year, and for the first time in a decade there was no pressure to find a deferment through grad school.

Not that Raven would have paid for it. That was the deal: I got a free education in exchange for a promise to not try to “find myself,” wherever it was I thought I might find myself.

The employment opportunity came courtesy of Raven’s network of friends, which was something I have always tried to remember. It also was a manifestation of the power of class taking care of itself.

Headquartered at 1221 Avenue of the Americas, McGraw’s tendrils reached first to St. Louis, and then through my reporting senior in Chicago. I was to cover a territory that rambled from Flint to Toledo, OH, but mostly covered the Wayne State-University of Detroit market, and the smaller colleges that existed then in the city.

Management knew the challenges of the traveling salesman well; the job title in fact was “college traveler.” My boss Dave knew the temptations inherent in continuing to live in Ann Arbor, and stipulated as a condition of employment that I live in Detroit.

Not having much alternative what with the uncertain economy laboring with the burden of Guns and Butter, I made plans to load my Chevy Vega mini-wagon with my belongings and move back to the City.

Porky was living at home then, between intermittent bouts of education in New Mexico. The end of the Draft was a godsend for him, since that enabled him to take a much more relaxed approach to formal education.

He suggested, successfully, that his parents Fleta and Jack rent me the empty maid’s quarters above the four-car garage of the mansion they had purchased on Afton Street. It was a spectacular residence, constructed in the 1930s in the Palmer Woods neighborhood just inside the city limits south of Eight Mile Road.

(The giant stove at the Fair Grounds. It was a wreck in 1973.)

Across the street was the Fair Grounds, where the gigantic wooden replica Garland Stove still stood to commemorate the old industry that had been supplanted by the automobile. It is one of the things that has been restored in the years since. Then, it was falling to pieces.

A Chaldean neighborhood sprawled south of there, and I can’t remember the name of the strip club directly across the boulevard, but it is long gone now.

Fleta and Jack, rest him, had made the bold decision to sell the pedestrian tract ranch house in Troy and move into the city. It was counter-intuitive at the time, since the city was unsettled, but the value of what they got in terms of the house was unreal. The place had been built to serve the needs of the owners of the Burton Abstract and Title Concern, and was a stone’s throw from the Dodge Brothers compound. The scions of the motor industry had created this little Oasis across Woodward Avenue from the Michigan State Fair Grounds.

Though the Barons were long gone for newer construction rout in Bloomfield Hills, the neighborhood was still upscale. Some white families hung on, reluctant to leave their old-school luxury; some newly-wealthy African Americans had moved in.

(Jack and Fleta’s place on Afton Street, Palmer Woods, Detroit.)

Soul Icon Smokey Robinson lived down the street, and the neighborhood association hired their own private security to keep out the riff-faff.

The value was extraordinary. There was the heavy brick and stone, laid in the English manner, with real ancient vines. Leaded windows, natch, butler’s pantry, attached greenhouse; walnut paneling throughout the main residence, and rosewood in my more humble two rooms up the narrow staircase from the garage.

Jack’s father Pop was living with them as well, and taking him in had been one factor in getting a place so big. I enjoyed watching the Watergate hearings with him as Dick Nixon’s presidency melted down, and on the whole, I was delighted with the situation. It was good to have some money of my own for the first time, and the rent was cheap and travel to the schools around town was opening up my eyes to all sorts of things.

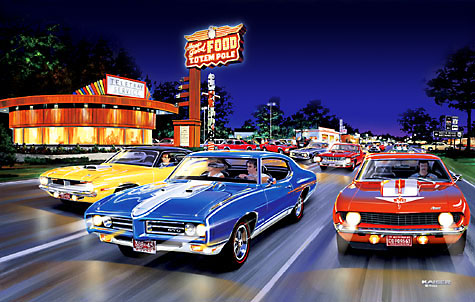

Magical Woodward Avenue was right there, and that six-lane road of dreams was as familiar as the back of my hand. It was where we cruised on high-school weekends down past Mavericks to the Totem Pole Restaurant in the hot cars that our fathers brought home from the Car companies.

(“Woodwarding” with a Hemi ‘Cuda, Goat and Camaro, 1973. Print by automotive artist Bruce Kaiser.)

MoPars for Dick, the rich kid, who had race-tuned Charger RT’s and Hemis at his disposal. There were Pontiac GTOs, Olds 442s and all the Pony cars- Mustangs, Camaros and Firebirds. I was stuck with an AMC 343 Javelin, but the car would do over 120 miles an hour even if didn’t get there quite as fast as some of the others.

Part of that was the politics of the summer. I did not pay a lot of attention to it, and don’t think I ever changed my voter registration from Ann Arbor to participate in the mayoral election. I actually voted for Dick Nixon the year before, not that I cared much for the man, but I wasn’t alone.

Dick buried George McGovern in the fourth-largest majority in the history of Presidential Elections. I didn’t have enough invested in Detroit politics to care whether Police Chief John Nichols was going to beat firebrand activist and state senator and insurance salesman Coleman A. Young.

LA had had Bill Parker, the ironclad police chief from 1950 until his death in 1966. He turned a corrupt, demoralized force into a feared paramilitary unit. Philly had Frank Rizzo, the self-styled “toughest cop in America” who went on to become it best-known police chief and later mayor of the City of Brotherly Love.

The Motor City had Big John Nichols. He was a bull-necked crew cut, blunt-spoken police chief who brooked no nonsense from criminals with his Tactical Units and STRESS, the acronym referring to “Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets.”

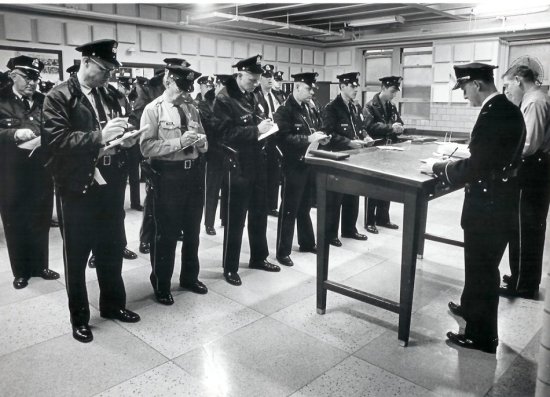

(Police Roll Call 1973.)

Roman Gribbs was the first (and only) Polish mayor in Detroit’s history. Big John Nichols was his chief of police, who was picked by the powers that be to succeed Gribbs. Nichols was one of the few city officials whose reputation was enhanced when he called for his calls for a strong police presence to crush the rioters.

The Unit was famous for shooting first and asking questions later. One of their favorite tactics was the classic set up. A decoy officer would be placed in a high crime area- the prototype for what NYPD Chief Bill Bratton called “CompStat”- and then conceal the tactical team around them.

When a mugging occurred, the officers would appear. The mugger, almost always black, had the choice of surrender, flight or fight. In the latter options, twenty young men were shot to death. There was tremendous support for the unit in the white community, and tremendous resentment about it in the black community.

Opposing Nichols was State Senator and community activist Coleman A. Young. Promising that he would disband STRESS, he proposed to put more cops on the beat and to set up mini-police stations in fifty different neighborhoods. Both men offered a variety of proposals for improved housing and transportation, but the issue was safety and why no one felt that way, black or white.

It was inevitable that there would be an African American mayor in Detroit, just as it was inevitable that a mostly white police force was going to have major problems. It was just a question of whether it was sooner, or later.

One issue that was far beyond the city limits at Eight Mile caused a little discussion in October of that year. Syria and Egypt attacked Israel in the Yom Kippur War. The rattled IDF experienced strategic surprise and the worst battlefield losses in its short history.

Prime Minister Golda Meir offered to fly to Washington to personally plead with President Nixon to resupply Israel.

(M-60 Tank rolls off a USAF C-5 Galaxy transport as part of Operation NICKLE GRASS- the emergency resupply of IDF equipment.)

The promise came from the White House, and was announced by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger: “The president has agreed, and let me repeat this formally, that all your aircraft and tank losses will be replaced.”

That was in early October of 1973. On October 16, 1973, the ministers of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries announced a decision to raise the posted price of oil by 70%, to $5.11 a barrel.

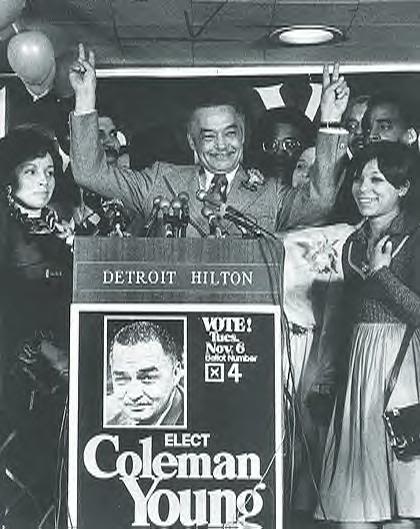

In early November, Coleman A. Young beat Big John Nichols by 15,000 votes to become the first African American Mayor of a major American city. In the middle of the same month, Dick Nixon announced that he was going to hit the brakes on the hot rods of Detroit- he was going to impose a 55 MPH speed limit.

(Mayor-Elect Young, 06 November 1973.)

Coleman Young immediately disbanded the STRESS unit, and issued a warning: “To all those pushers, to all rip-off artists, to all muggers: It’s time to leave Detroit; hit Eight Mile Road! And I don’t give a damn if they are black or white, or if they wear Superfly suits or blue uniforms with silver badges. Hit the road.”

In a way, all of us complied. White Detroit just hit the road a lot slower than it would have before the gas prices went up. The whole thing was going to affect the city like a trip to the back of the moon.

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com