ERNIE (and Mac’s) WAR

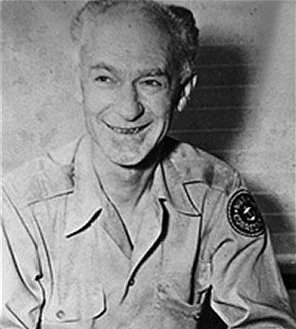

(WWI sailor and WWII War Correspondent Ernie Pyle, seen here on USS Cabot when he was making waves with the Navy Department. Mac met him on Guam with the CINCPAC forward staff. Photo US Navy.)

I tried to look at my notes from the most recent session with Mac at Willow and they are not making much sense. Topically, the conversation appeared to have veered from:

The excellent nature of the Gruyere Cheese puffs, the superb taste of the crackling Peking Duck pancakes, a nurses report from INOVA Fairfax that revealed nothing wrong with a Granddaughter, 50 miles covered in the champagne Jaguar, gall bladders, fried chicken done to perfection early in the last century, the obits of two men I did not know, the status of traffic on I-66 eastbound, and what the six fire trucks and twenty-five police cruisers were up to, details about Section 66 of the Arlington National Cemetery, and in-ground placement of funerary urns therein, the deficiencies of the original Columbarium at the National Cemetery, the status of Katia the bartender’s job offer from outside the food, beverage and hospitality industry; whether the consolidation of the weather guessers, Cyrppies, Public Affairs and Intelligence Officers in the Corps of Information Dominance was ‘back to the future,’ since Mac had started as a special investigator who did PAO stuff at the Naval District in Seattle in 1941.

I was not making much progress on my happy hour white, since we were all over the map, narrative-wise. “So you were really a Public Affairs officer before you were a codebreaker, right?”

Mac noded. “It was part of the Office of Naval Intelligence,” he said. “I guess they thought it was all information and pretty much the same thing.”

“Maybe they do again,” I said. I finally asked Mac about Chester Nimitz, the phlegmatic Texan who led the Navy’s drive west across the Pacific.

Mac was much more focused on this, and it was a little unusual, since the mythic figure of the Fleet Admiral normally was part of the backdrop to his part of the war, large as life as he was.

Mac furrowed his brow, attempting to distill the legend from the man. “Well,” he said slowly. “He took care of his Enlisted guys- the ones in the motor pool and the boat detail for the Flag Barge.” He went on to describe his direct conduit to the troops, a Mustang Lieutenant who had enormous impact on the staff and the way it worked.

I made a note to find a roster of the staff from 1945, and see if I could track down who the officer had been, since he showed up again as an agent of influence who secured the Junior Officer BOQ across from the HQ after the war- where the chapel is now. It was a rare name that Mac did not remember, or did after I was scribbling something else. I made a note to check it out and ask more questions.

Mac was still contemplating the Public Affairs question. “It was interesting to see who came forward to Guam when we were there. The European war was over. All sorts of people showed up. Like Ernie Pyle, the war correspondent.”

“He was the most famous correspondent of the War- probably more so than Edward R. Murrow. Did you ever meet him?”

“Oh yes. He was on Guam before the invasion. Ernie was shot by a Japanese machine gunner on Ie Shima, Okinawa.”

“There is quite a display for him in the Hall of Correspondents in the Pentagon, and I would stop and read the panel display when I spent more time than I wanted walking to and from press conferences with The Joint Staff. Ernie was known as the soldier’s correspondent, according to the display. Did you ever have drinks with him?”

That is the way of these conversations- I had no inkling whatsoever that in the course of this session we would stumble across the most iconic and tragic media figures of the war in Europe and the Pacific, two theaters whose paths seemed rarely to cross.

“Not true,” said Mac. “Don’t forget Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, F-R-A-S-E-R, he spelled out. He came to the Pacific to command all British naval forces after commanding the group that sank the Nazi battleship Scharnhorst off Norway.”

“Point taken, Sir,” I said, and that led to a discussion of the wild four-day party that started on board Cagey Five, the battleship HMS King George V.

“But you actually met Ernie Pyle? That is incredible.”

The Admiral shrugged. “He was there, it was a small island. He had sort of prickly relations with the Navy, since he thought the sailors had it pretty cushy compared to the combat infantry of the ETO. He was a plain-spoken SOB and he wore his heart on his sleeve.”

“He might not have thought that if he saw the results of a running naval gunfight like the battle for the Slot was,” I said indignantly. “I just read ‘Neptune’s Fury,’ Jim Hornfischer’s account of the slaughter. I have never been so horrified in my life of the account of close-in naval gunfire.”

Mac looked on with the cool perspective that only ten decades on the planet can give you, and know you are the last man standing from all the proud formations so long ago. “It is one thing to read about it and quite another to live it. Ernie had a point. He got bombed with our guys by the Army Air Corps at St. Lo, and was badly shaken. His heart was always with the riflemen of that war. In 1944, he wrote a column urging that soldiers in combat get “fight pay” just as airmen were paid “flight pay.” He pursed his lips in contemplation. ‘Congress passed a law authorizing $10 a month extra pay for combat infantrymen. The legislation was called ‘The Ernie Pyle Bill.’ That was the mark of the depth of fondness the troops had for him.”

“Sounds like Bill Mauldin and his ‘Willie and Joe’ cartoons.”

“Close enough,” said Mac. “And you can throw Andy Rooney in that group, too. Andy was one of the angry young men, back then. Ernie was an old man, though- he was 45 when he was shot. I remember thinking about that at the time- I was still in my mid-twenties and he was old enough to be my father.”

“Do you recall how you heard about his death? Did you have to clear the dispatches or the pictures before they went back to CONUS?”

Mac shook his head. “Not that I recall. There was a picture I might have seen at the time, but it never was published. I think it was the middle of April in ’45. He went from Guam to Okinawa to cover the action. These days, you would say he was ‘embedded’ with the 77th Infantry Division.”

“He took all the risks that the grunts did,” I said. “That is a commitment to the mission.”

“Yes, I think so. He was riding in a jeep with the CO on an infantry regiment and a couple other guys. Apparently hundreds of vehicles had driven the same road, but for whatever reason, a Japanese machine gun opened up on them. They stopped the jeep and everyone jumped into the ditch. Apparently Ernie raised his head to ask the Colonel if he was OK.”

“I think I heard he was killed by a sniper,” I said, stopping my scribbling.

“Nope, it was a Jap machine gun that had played possum, letting hundreds of other vehicles go by. Those were Ernie’s last words, though. He took a round in the temple, and was killed instantly right after he asked.”

“Maybe that is why the machine gunners waited, since they must have known that opening up would get them killed pretty quickly. That is a powerful argument for keeping your head down,” I said.

“Yes indeed. I am sure Ernie would have preferred for it to work out differently. They Army buried him with his helmet on with a bunch of the other combat dead. He was one of the few civilians to be awarded the Purple Heart.”

(Ernie Pyle shortly after being killed. US Army photo by Alexander Roberts).

“Wait, I saw his grave at the Punchbowl in Honolulu!” I said.

“Ernie traveled a while after the war. They exhumed him from the grave in Ie Shima, and then buried him in the Army cemetery on Okinawa, and then finally they moved him to the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific where you saw him.”

“That is amazing,” I said. “He was the most-read correspondent of the war.”

Mac nodded and finished his Bell’s Lager. “He even impacted the Japanese. When Okinawa was returned to Japan’s control after the war, Ernie’s monument was one of only three American memorials allowed to remain in place.”

“Huh.” I fished around in my wallet, and the Admiral picked up the tab, which was modest since thanks to the pro-active memo written by Elizibeth-with-an-S he drinks for free now at Willow.

We settled up with Liz-S and Jasper, the best bowler on Guam, and I went to find the Admiral’s walker, one of the ones with hand brakes and quick action movement. I walked back across Fairfax Drive with him until he turned off at the entrance to the Madison. I retrieved the Bluesmobile from the Bat Cave under the hotel and drove home.

Once I opened the mail, I poured a tall one and logged onto the ‘net. I checked out the Ernie Pyle Monument, in place for 67 years:

AT THIS SPOT

THE

77TH INFANTRY DIVISION

LOST A BUDDY

ERNIE PYLE

18 APRIL, 1945

Copyright 2017 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com