First in Defense

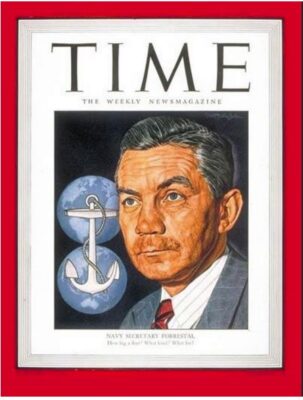

(President Harry Truman Appoints SECNAV James V. Forrestall as first Secretary of Defense. Photo AP).

In 1947, President Harry Truman appointed James V. Forrestal as the first Secretary of Defense. Forrestal had three or four areas of controversy with the Administration. First was the amount of money the new unified Department would spend to clean up the vast stocks of weapons left over from World War II. Second would be the details of the Defense unification with details that were still unresolved. An effort to reach out to Republican Tom Dewey, who looked to win the 1948 General Election. The last controversy was one in which Forrestal found himself in agreement with his elected President: he continued to advocate for complete racial integration of all the Services, a policy implemented in 1949 and marked one of the first major steps in the Civil Rights struggle that would define the 1950s and ’60s.

There is another echo of Forrestal’s tenure today in what then was known as Palestine. During private cabinet meetings with President Truman in 1946 and 1947, Forrestal had argued against Partition of Palestine on the grounds that it would infuriate Arab oil producing nations that supplied the economy and defense establishment of the United States. That is not dissimilar to the struggle that has gone on since Israel’s establishment in 1948.

Instead, Forrestal favored a federalization plan for Palestine. Truman was curiously silent on the issue and the response of the Democrat wealthy donors was immediate. President Truman received threats to cut off election financing as well as hate mail accusing him of “preferring fascist and Arab elements to the democracy-loving people of Palestine.”

Forrestal was appalled by the intensity and implied threats over the partition question. He appealed to Truman to not base his decision on partition in two cabinet meetings. As part of that, his only known public comment on the matter was made. He reportedly told Senator J. Howard McGrath (D-RI) “…no group in this country should be permitted to influence our policy to the point it could endanger our national security.”

Forrestal’s statement soon earned him the active enmity of some congressmen and supporters of Israel. He was also an early target of sensational journalist Drew Pearson, who was an opponent of policies hostile to the Soviet Union. He began to regularly call for Forrestal’s removal after President Truman named him Secretary of Defense. Pearson was raising a protege of his own in the person of Jack Anderson. Pearson reportedly him that he believed Forrestal was “the most dangerous man in America” and claimed that if he was not removed from office, he would “cause another world war.”

Upon taking office as SecDef, Forrestal was surprised to learn that the administration was not budgeting for the return to peace. Truman was known to approach defense budgetary requests in the abstract, without regard to defense response requirements in the event of conflicts with potential enemies. The president would begin by subtracting from total receipts the amount needed for domestic needs and recurrent operating costs, with any surplus going to the defense budget for that year. The Truman administration’s readiness to slash conventional readiness needs for the Army, Navy and Marine Corps while attempting to build a new Air Force soon caused fierce controversies within the upper ranks of the newly unified U.S. armed forces.

At the close of World War II, millions of dollars of serviceable equipment had been scrapped or abandoned rather than appropriate funds for storage costs. New military equipment en route to operations in the Pacific theater was scrapped or simply tossed overboard. Facing the wholesale demobilization of most of the US defense force structure, Forrestal resisted President Truman’s efforts to substantially reduce defense appropriations, but he was unable to prevent a steady reduction in defense spending. The resulting major cuts impacted not only defense equipment stockpiles, but also in military readiness.

By 1948, President Harry Truman had approved military budgets billions of dollars below what the services were requesting, putting Forrestal in the middle of a fierce tug-of-war between the President and the Joint Chif of Staff. Forrestal was also becoming increasingly worried about the Soviet threat as his 18 months at Defense came at an exceptionally difficult time for the U.S. military establishment: Communist governments came to power in Czechoslovakia and China while the Soviets imposed the blockade on West Berlin.The resulting Berlin Airlift to supply the city demonstrated the course of what would become the Cold War norm. The war between the Arab states and Israel after the establishment of Israel in Palestine increased pressure on Europe as the NATO Alliance was being formed.

The international situation was chaotic, with Soviet take-overs of much of Eastern Europe and political campaigns against the governments of Greece, Italy, and France. The invasion of South Korea by communist North Korea would eventually demonstrate the legitimacy of Forrestal’s concerns, but Truman and his cabinet , but at the time these were not shared by the President or the rest of his cabinet. Presidential candidate Dwight D. Eisenhower was in agreement with Forrestal’s theories on the dangers of Soviet and International communist expansion. Eisenhower recalled that Forrestal had been “the one man who, in the very midst of the war, always counseled caution and alertness in dealing with the Soviets.”

Eisenhower remembered on several occasions, while he was Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, he had been visited by Forrestal, who carefully explained his thesis that the Communists would never cease trying to destroy all representative government. Eisenhower commented in his personal diary on 11 June 1949, “I never had cause to doubt the accuracy of his judgments on this point.”

Despite his opposition to the unification to the unification of the military services, Forrestal helped develop the instrument of transformation that was the National Security Act of 1947. That legislation created the National Military Establishment, while the Department of Defense was not created as such until August 1949. With former Secretary of War, Robert P. Patterson’s retirement, Forrestal was the next senior remaining to fill the new position, and ease the pains of integration.

Forrestal met privately with Dewey privately and the two came to an agreement that he would continue as Secretary of Defense under a Dewey administration. Unwittingly, Forrestal would trigger a series of events that would not only undermine his already precarious position with President Truman but would also contribute to the loss of his job, his failing health, and eventual demise. Weeks before the election, Columnist Pearson published a press exposé of the meetings between Dewey and Forrestal. In 1949, angered over Forrestal’s continued opposition to his defense economization policies, and concerned about reports in the press over his mental condition, Truman abruptly asked Forrestal to resign.

By March 31, 1949, James V. Forrestal was out of a job. He was replaced by Louis A. Johnson, a vocal supporter of Truman’s defense retrenchment policy and a war in Korea that would establish much of what we have come to accept as reality today. There is more about Secretary Forrestal’s departure from elected office that may have additional insight into the removal of senior government managers like the Kennedys, Nixon and most recently another.

It is another story we may get to tomorrow. But was it suicide or murder? We will try to get to that as this story unfolds….

Copyright 2024 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com