First Ones Back

I stood on the 50thth Floor of a proud new building on the bank of the river. She lay there below me, enigmatic. Her curves and contours were lit by the full-silver moon. She showed her considerable charms with an insouciant and aggressive charm.

For a woman of her age she carried it well. It showed an odd combination of her flesh, and estate jewelry and the flashy brass of her new geometric jewelry. By her subtle shape she showed an elegance of an age we do not now know, though she intentionally showed it. She was an ancient tease, and she knew it. She had been all things to all people in her time, ravished but victorious against a host of needy lovers. Tender or abusive as they had been, they were gone and she remained. She was triumphant.

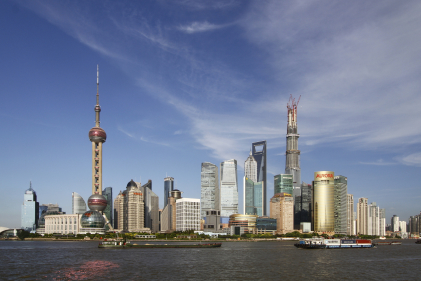

She was Shanghai. I know what I had expected- I was probably as surprised as the tourists from the 1920s and ‘30s who were astonished to debark from their ships into a place that looked as Western as Chicago. Perhaps I had been expecting a version of the Wanchai district of Hong Kong. It was not. I was a high-speed elevator from the streets of the Pudong New Area halfway up the third tallest building in the world.

I looked down at the nighttime city across the Huangpu River and saw the past. The Bund, the three-mile stretch of riverfront, was the heart of the European concession. The solid European buildings along the river’s edge had been designed to show the dominance and eternity of the Western Empires. It was the Wall Street of the East, sixth largest city in the world.

Now the Chinese keeps the Bund as a token of a stolen moment, a time when the Middle Kingdom did not rule all before it.

In that incarnation, Shanghai dates to 1842, after the British won the First Opium War. You can understand why there was some resentment- the Qing Dynasty generally opposed the creation of tens of millions of addicts due to the drug trade.

China sank into the status of a vassal states. The Wings were allowed to stay on, but the most important cities and prime real estate were parceled out to the “concessions” controlled by colonial powers.

With American-educated Dr. Sun Yat-sen’s revolution of 1911, the Qing Court was sent packing, and the next few decades were spent under an aggregation of competing Tongs, nationalists, warlords and the colonial powers. Life in Shanghai was racy and continental. Hollywood and London society traveled there regularly. Art Deco buildings soared against a skyline that resembled London more than Nanking.

The Chinese Communist Party was founded in July 1921, and looked to Lenin for inspiration in establishing a new and independent paradise. , a fourth player entered the fray.

Shanghai was the world’s third most important banking capital and vibrant financial center of East Asia. It was also two cities, one being the Shanghai of the Bund, and the other under the authority of the ineffective and corrupt Chinese government. The British, Americans, French and the Japanese, after the conclusion of First Sino-Japanese War in 1895.

The burgeoning Japanese Empire coveted the Middle Kingdom. In 1931, the Japanese invaded and established the puppet state of Manchukuo, which would last until the a-Bomb put an end to the Empire of the Sun.

Though the brutal suppression of the people of Nanking, Shanghai partied on with an increasingly sense of abandon. That ended on Pearl Harbor Day, 1941. The concessions were occupied and the exclusive Shanghai Club was commandeered by the Japanese Navy, who “cut down the legs of the club’s famous pool tables so they could more easily play billiards.”

Many of the foreigners who ran day-to-day operations in the International Settlement remained at their jobs until after February 1943, when they were marched off to concentration camps and interned.

That same month, Britain officially signed the International Settlement over to Chiang Kai-shek’, while the Japanese were still running the place. After V-J Day, Shanghai was once again under the control of the Nationalist government though the war with the People’s Liberation Army still raged.

Former President Jimmy Carter was on USS Pomfret (SS 391) on the 1949 WESTPAC patrol that included the last US Navy port call in Shanghai before the Reds took the city on May 27, 1949.

Things then moved swiftly for the old Colonial city. A year later, hundreds of “imperialists, feudalists and bureaucratic capitalists” were executed at the Canidrome, the dog track and nightclub complex in the French Concession to cheering thousands.

A decade before, African American jazzman Buck Clayton had serenaded Shanghailanders in the same place. The sophisticates reportedly had danced as if there were no tomorrow. There was one, of course, but it was not quite what anyone would have expected for the most sophisticated city on the planet.

Deep Freeze. Cultural Revolution. Nixon.

My pal, Left Coast Guy, was on board USS Blue Ridge (LCC-19) for the historic port call 19-23 May, 1989, that opened the city once more to the West. My son is on that ship today, on the same staff.

Small world.

LC Guy recalls that it “was an interesting time in many ways.”

The timing of the visit was coincident with the Tiananmen Square demonstrations that were heavily covered in the international press and on television. Approval for the visit had come before the demonstrations were global news, and we were back in Yokosuka before the 4 June massacre. More on the political environment shortly.

We were lead ship of three; the cruiser USS Sterett and the FFG Rodney M. Davis trailed us up the river. The sea and anchor detail lasted at least half a day.

As we approached the river, still miles out from the mouth, the sea turned the yellow of the silt that washes down in colossal amounts. Someone with ship engineering skills commented to me that the water intakes and filters would find that interesting. The greater concern was water depth—the sonar dome on Sterett would have little clearance if the charts were right and we just had to go with the assurances of the Chinese and trust the pilots to keep us near the deepest water.

Steaming up a river for hour after hour is just not a normal thing to do in WestPac, so it was quite interesting to just watch the world go by as the ship drivers worried the hard stuff. There were several naval and coastal defense facilities along the way, interesting electronics, etc. I didn’t have to collect the data so I could relax and look for surprises. Military facilities and ships exchanged gun salutes with us, and the Sailors and Marines manning the rails earned their pay.

We tied up right on the Bund, which looked then pretty much as it does now, and did decades before. Across the river in 1989, Pudong was a gritty industrial area, and now, of course, it is the site of the new city center and some of the tallest buildings in Asia. On my last visit, a couple of years ago, I stayed on the 76th floor of the Hyatt—the expensive rooms were on higher floors. I could look up at the building that looks like a bottle opener and one much higher than that is now in place. All this was not there and hardly contemplated in 1989.

The pollution is even worse now than it was in 1989, and back then we all saw that the city was cloaked in coal dust and soot. All of us were required to wear whites and use the buddy system, so we stood out like binary stars in early evening everywhere we went. The Chinese admired our prosperity, and understood it, even as they clamored for democracy, which was, and is, somewhat alien. To see us walking their city in bright white uniforms was quite shocking to many Shanghainese. Absurd. After four days of it, with clean uniforms even then, they were impressed.

The democracy movement might have been bigger in Shanghai than it was in Beijing. The population then was 12-13 million, fluctuating daily as the workforce came and went. There were massive demonstrations in the streets, with a local version of the Goddess of Democracy. We were told to not “participate” in any political activity but everywhere we went people waved, smiled and gave us the peace sign. They knew that we represented the most powerful democracy and they saw that if nothing else, in our whites, we were the Gods of Prosperity.

There were many expat bars even then and other bars and restaurants, with Chinese clientele, who were interested in our patronage. My friend Fred the Marine, part of the N2 staff, had some Chinese language skills. On the first of second evening there we arranged to meet at a particular Chinese bar that was relatively seedy but probably safe. Another staff officer and I arrived and sat at the bar enjoying the first beer of the evening.

After 10 minutes or so, the phone rang behind the bar, the bartender answered, turned, and said “(a bunch of Chinese) Guy? (a little more).” I looked at him and he looked at me. He said: “Guy?” I nodded and he handed me the phone. It was Fred. He had just wanted me to have the experience of getting a call in the bar. I turned to my buddy and said: “That was not my wife.”

On our last evening out before departing Fred and I were with some others in a bar packed with democracy protesters. A hush came over and the radio was turned to high volume for a man’s voice in harsh Chinese.

It was Li Peng, announcing the end of tolerance for the democracy protests in the Capitol. Fred translated key parts as it went. A local protest leader was at the bar with us and he looked grim as the speech ended. Fred translated as I asked him what will happen now. His answer: “Many will die.”

The Chinese flocked aboard all three ships in great numbers and they seemed to enjoy it very much. At one point a dead body became wedged between two of our ships, having floated down the river to the obstruction. The Officer of the Deck was about to secure visiting and pointed out the problem to his Chinese counterpart, who shrugged and said that this happens a lot and that the people won’t be bothered by it. The local authorities took care of it in short order.

There were a few military to military events, a vast banquet with an extraordinary proportion of completely unrecognizable foods. Most of it tasted great, although there were a few textures that I hope to someday forget. A group of us were invited to board an “operational” Chinese submarine, which was too good for any intel guy to pass up.

It turned out to be an old Ming boat with wooden cabinetry and paint covering valves that obviously hadn’t turned in some time. They made us enter via the forward torpedo loading hatch, which was evidently used for training, or just greased up in preparation for our visit, as the effect on our whites was predictable.

It was historic indeed to be the first U.S. Navy warships to visit the city since the establishment of the People’s Republic, but in the context of the democracy movement and the joy of a new port, no one spoke much of that.

This was my last port visit of that tour on the C7F staff. The family flew out at the end of the month for a short vacation in Hawaii en route the next assignment. I made a courtesy call on then CAPT Mike McConnell, CINCPACFLT N2, as the Beijing massacre was being reported.

Gentleman that he was and is, he took the time to ask me smart questions about the China I had just left, to better inform his support for the CINC. I’m not sure I had anything of value to offer, but sitting in his office, watching CNN as he ran off periodically to meet with the CINC and staff, is a treasured memory in itself.

Copyright 2014 Vic and LC Guy

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303