For Whom the Bell Tolls

Eddie the Docent waved elegantly to the crowd of tourists, some covered in oil, who stood around the Hemingway dining table under the fine Venetian glass chandelier favored by Ernie’s second wife Pauline.

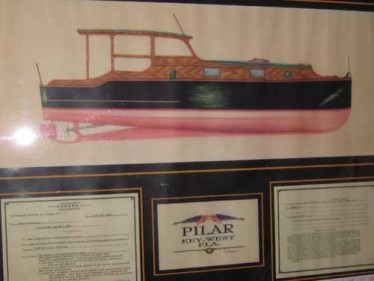

“He won the Pulitzer Prize for The Old Man and the Sea,” part of a somewhat disjointed narrative caused by the linear progression of the tour from the living room to the of the Hemingway residence in Key West through the hall, where a rendering of the fishing boat Pilar hung on the wall.

The jumble of Hemingway’s life made the short hand account of the detritus of a famous life confusing. Pictures of the four wives hung on the wall, along with Ernie, past and future, for ease of unscrambling things for the docents.

It did not help me. I looked over at my associate. “It was the fucking Nobel Prize, right?” and he nodded.

I had announced to the sleepy gatekeeper that I was arriving as a delegation from Walloon Lake, and Papa’s early incarnation in the great Northland, the time of his Nick Adam’s stories.

I presented my credentials to receive the military discount, while my associate presented his Florida Driver’s license with local address. “Local,” he announced. He was rightly proud that his status as such gained him free admittance to the home on The National Historic Register.

“Alien,” I said, thinking of the Conch Republic, but the gatekeeper was a local, too, and he just nodded and responded that they had a lot of them around town.

“I’m undocumented,” I said firmly, thinking that this would be a great place to park myself for a few months and change my status. A lot of places claim Ernie, including Uncle Fidel from his time in Cuba, but I have to think that he was actually the ultimate snow-bird, flitting away to some other continent or war when it got too hot and humid and sweat rolled down under the loose guayabera shirt.

The stately home up the brick walk with the wide verandas had been Ernie’s place, purchased by Pauline’s brother, from 1931 to 1939. That was after the split-up with Hadley, Pauline’s best pal, and the moving feast of the Paris years and I wondered how all that hung around the breakfast table.

Ernie heard of Key West from his pal and literary icon John Dos Passos. He and Pauline paid a visit on the way back from Paris, a roundabout stop, and they were enchanted. Ernie felt it suited him right down to the ground.

“It’s the best place I’ve ever been anytime, anywhere,” he declared. “Flowers, tamarind trees, guava trees, coconut palms…Got tight last night on absinthe and did knife tricks.”

We might have done some of that the night before, though some of the details were a little hazy. Ernie and Pauline rented on the island for a couple years and eventually bought this house at 907 Whitehead Street with a then-hefty loan of over twelve grand from Pauline’s rich Uncle Gus.

It was one of the biggest places in Key West, and famous long before Expat Ernie showed up. The original builder had actually put a cellar in the place, maybe one of the only ones in Monroe County, out of a sense of correctness brought from Up North.

It turned out the Eddie and I were both correct about the respective prizes, but an uneasy feeling crept over me after the perceived discontinuity and my associate and I wandered away from the group and walked out by the pool.

The long placid aqua waters of the bathing facility had their own story, a rectangular fantasy in concrete that had to be carved out of the hard coral soil at vast expense, and prompted Ernie to place a penny in the concrete at the end of it, signifying that he was flat broke and his last coin was going into the pool.

“There used to be a walkway from the bedrooms upstairs over to the writer’s loft over the carriage house,” said my associate, shaking his head. “The quality of the docents has declined over the thirty years I have been coming to this place.”

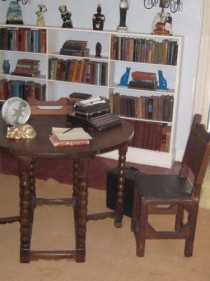

We commiserated on the general decline of all things as we labored up the stairs to the office where Ernie worked, pecking out the stories of the ‘30s, wondering about how everyone we knew had gotten so old.

Gazelles and Antelope heads hung on the wall. I marveled at Ernie’s discipline. He insisted on working in the morning, even in the face of absinthe and knife tricks in the night.

Ernie really got around, despite his time in this lovely place, and he was getting me disoriented. If he was not here, at the original Sloppy Joe’s, he was trout fishing in Michigan, or conducting imaginary ASW patrols in his cruiser, or wandering below the snowy slopes of Kilimanjaro or summering in Cheyenne or contemplating the end of things at the wrong end of a shotgun near the new resort at Sun Valley.

Time being what they were when I was coming up, performance artist and disorganized author Hunter Thompson had been a role model, but I was increasingly realizing that he had lifted a large slice out of Ernie’s playbook, which was to roam the world looking for interesting places to drink. For Hunter, the business model was to operate under threat of bankruptcy, writing about it on deadline.

Ernie was much more methodical about his craft.

I am not going to throw any coconuts at anyone, each to their own, since those who live in glass houses ought not to parade around in the buff, so let’s just leave it at that.

Ernie had the guts to actually live with four women and love more, which is quite beyond me, but it had been a decent enough year in which I had stumbled over Ernie’s ghost more than once, at the Park Grill, and the old store in Horton’s Bay and now here in Key West.

In the depths of the winter in Michigan I stopped by the Park Grill in Petoskey where Ernie used to drink after he came home from the war, a decorated ambulance driver who was infatuated with one of the high school lovelies and used to wait, in uniform, for her to get out after the last bell.

The city fathers ripped down the old high school entrance where he waited, much to Mom’s dismay, since she had documented the rooming house where let a room, and struck up an acquaintance with the last living soul in town who knew Ernie in person.

She was a feisty old lady, who I heard one summer at one of Mom’s galas at the old train station where Ernie would debark on his jaunts up from Chicago. She was proud to say that she had not slept with him. “We just played tennis,” she was fond of saying.

She seemed to think that she had played Ernie better than some of the other

women in his life, and I am not sure she was wrong. No wonder he drank, and no wonder she outlived him by a half-century. She didn’t hear the same sort of bells that Ernie did.

“Writing, at its best, is a lonely life. Organizations for writers palliate the writer’s loneliness but I doubt if they improve his writing. He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.”

– (Banquet Speech for the 1952 Nobel Prize for Literature penned by Ernie. He may have suspected that the award was influenced by reports of his death by plane crash in Africa the previous summer.)

Copyright 2011 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com