Grant’s Goat

It is all about choice, you know? General Lew Wallace had a choice about the road he took to get to the Pittsburg Landing battle at Shiloh. I showed you a picture of the bend in the Shunpike- the spur to the left would have taken Lew Wallace’s Division to the River Road, and thence south to Pittsburg Landing. The Shunpike offered a direct and less muddy route to the Union right flank, defended by Tecumseh Sherman.

When it comes to Civil War history—or any history for that matter—there is often a vast difference between what actually happened and what people believe happened. There are people who care deeply about all this, and invest enormous emotional capital on what might have been the intentions of the men on the field. So, here is the situation on that muggy morning.

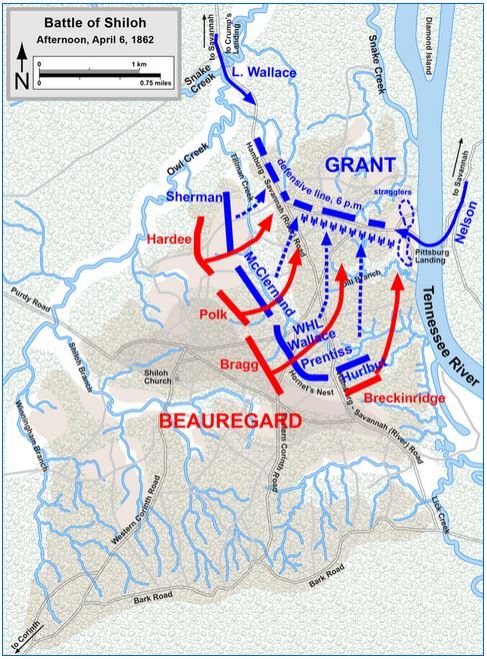

It is nine o’clock. Grant has arrived at the landing to confront a scene of chaos as Albert Sidney Johnson has attacked with decisive force- 50,000 confederate troops. For Grant, the situation has the hallmarks of an impending disaster. He decides to visit each of his commanders in the field, a trip along the lines that took him to Sherman’s headquarters on the extreme right of his line. He told an aide to get word to Lew Wallace that his presence on the field was necessary. Someone wrote it down, and a courier was dispatched to Crumps Landing. When Grant arrived on the ragged right wing, he told Sherman that Lew Wallace was on his way.

The copy of the order did not survive the battle, and the controversy began. Was Wallace directed to take a route, or did he have commander’s discretion in executing the order that Grant never saw written down.

Lew Wallace was a careful man, and apparently a caring one. Before advancing to meet Sherman at the Hamburg-Purdy Road, Wallace allowed his men a light lunch to prepare for the five-mile march down the Shunpike and Purdy Road. Only one major barrier to cross-country movement would hinder the progress of his Division: the Snake Creek.

Before completing the crossing of Snake Creek, staff Captain Rowley reached Wallace with the news that the right flank of Grant’s army was now disorganized and had been pushed back closer to Pittsburg Landing. The Federals no longer controlled the Purdy Road Bridge over Owl Creek, nor the position where the road approached the field of conflict.

Now consider that this was Wallace’s first Division-level Command, and that he was not a professional soldier. In other circumstances citizen-soldiers have ordered arcane maneuvers that worked out pretty well.

I am thinking of Joshua Chamberlain and the 20th Maine at Gettysburg. His position was the extreme left of the Union Line. Knowing that his men were out of ammunition, and judging that another charge by John Bell Hood’s Alabamans would prevail, he ordered an unusual maneuver: he ordered his left flank to advance with fixed bayonets in a “right-wheel forward” maneuver. As soon as they were in line with the rest of the regiment, the remainder of the regiment charged. The simultaneous frontal assault and flanking maneuver befuddled the 15th Alabama, which was broken.

Upon hearing that he could not proceed directly, Wallace decided on a “countermarch” maneuver. sending the lead brigade back through his column. This complex and rarely drilled evolution meant that his forward brigade would have to march through itself (think of a college marching band at half-time) and two other brigades stretched across three miles of road. He could, of course, have just turned the division around, but that would have resulted in a sequence in which the units he intended to keep in reserve would arrive in combat first, rather than last.

In the meantime, Sherman had fallen back to a position near the Hamburg-Savannah Road, determined to hold a bridge over Snake Creek, which he predicted to be Wallace’s fall-back line of advance.

I don’t know what the teamsters of the 72 OVI thought about the unusual maneuver, as the vanguard of the force reversed course and filed back through the line of advance. assumed would be Wallace’s second option. Wallace got his vanguard back to the River Road and moving down to Pittsburg Landing by 1430 as the fighting raged. Grant needed every man to stave off the Confederate on his center, a fury of combat along a sunken road that became known as the Hornet’s Nest.

Grant was agitated, and dispatched two staff officers to find Wallace’s Division, since the 5,800 soldiers might provide the winning margin. Lieutenant Colonel James McPherson and Captain John Rawlins followed a circuitous route to Overshot Mill on the Shunpike where they encountered the rear elements of the formation proceeding to the River Road.

Finding Lew Wallace further down the column, McPherson informed him the situation at Shiloh was dire, and urged him to hurry to support Grant. In curious decision, based on what he had been told, Wallace then told his lead men to take a break until the rear of the column closed up.

This delayed the advance for more than an hour, and he did not reach the battlefield until shortly after 1830 when the day’s fighting had died down. Wallace’s men had marched about 14 miles in nearly seven hours over roads that had been left in terrible condition by recent rainstorms and churned by previous Union marches. Wallace directed them to take up positions on the Union right, as Grant had directed that morning.

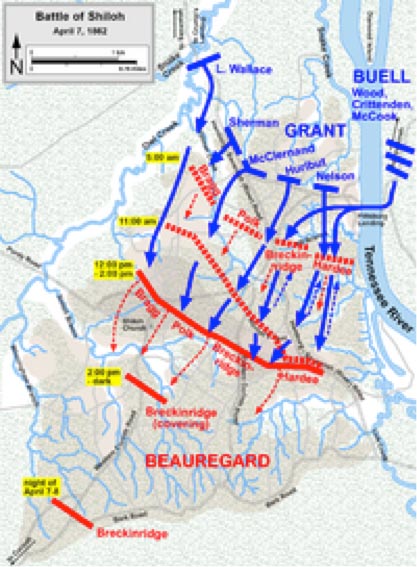

(Map of the Battle of Shiloh, Day Two, April 7, 1862).

The next day, April 7, two of Wallace’s batteries, augmented with another from the 1st Illinois Light Artillery were the first to attack, just at first light. Sherman and Wallace troops helped force the Confederates to fall back, and by 1500 that afternoon, the Confederates were retreating southwest, toward Corinth.

I think the real culprit in the whole affair was probably miscommunication, but it was clearly an example of spin. It’s possible that Grant’s orders, as written, directed Wallace to come in by the River Road, and Wallace, for whatever reason, elected to ignore that part, and take the Shunpike instead. It’s possible that this happened, and I’ve seen it speculated. But we can never really know. But I think it’s just as likely, if not more so, that Wallace simply made an honest mistake.

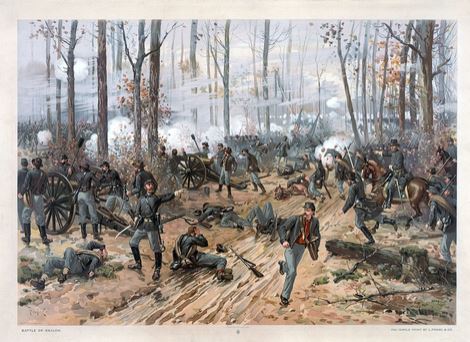

The Union won the battle, and Grant, as well as his men, had fought hard and well. But Grant did, of course, come in for what may very well have been the most severe criticism he faced during the entire war. The issue was connected to the sheer magnitude of what happened at Shiloh. The two-day battle produced more than 23,000 casualties and was the bloodiest and bloodiest encounter of the war to date.

Actually, it was much more than that. The number of killed and wounded from simply dwarfed everything that had ever come before, in all of American history. Nothing else was even close. People in the North were stunned by the casualty figures.

Keeping in mind here that we’re talking the spring of 1862, before the war had evolved into the bloodbath we now think of, the numbers from Shiloh were almost beyond comprehension. Combine those two things – a staggering number of dead and wounded, and reports in the papers that Grant allowed his army to be caught totally off-guard. It wasn’t true, or at least not completely- but we are aware of how this works in the public mind, and the search for the guilty began.

Someone had to pay for the negligence that led to all that butchery. And that someone was going to be Grant, unless another scapegoat could be found. As it turned out, Lew Wallace was just the man for that. It took years for Grant to relent in his assessment, and Wallace was relieved of command. He did not get another significant field assignment until 1864, when he may have saved the Capital from the depredations of Jubal Early in the battle at Monocacy Creek.

If Wallace had not delayed the Rebels, they might very well have penetrated the District from the north, with the goal of burning the city and perhaps capturing President Lincoln.

Despite that remarkable success, and the many positions of authority he occupied after the war, the “Slanders of Shiloh” were always with Lew Wallace.

My Great Great Grandfather, to the best of my knowledge, had no responsibility for the tardy appearance of his unit on the field. He would have been too junior a soldier to have made an effective goat. Besides, the 72nd OVI had business to conduct at Corinth.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303