Labor Day & the Pullman Strike

It is a holiday today as you may have heard. It is supposed to be commemorating the value of “labor,” and thus as a nation we are taking the day off to celebrate it.

Other nations around the world do the same thing, though they celebrate a sort of energetic response earlier in the year. Our version has become a marker for seasonal change, the big transition that ends the Summer and marks the beginning of the school year here in the northern latitudes. And the preparations for longer nights and colder temperatures.

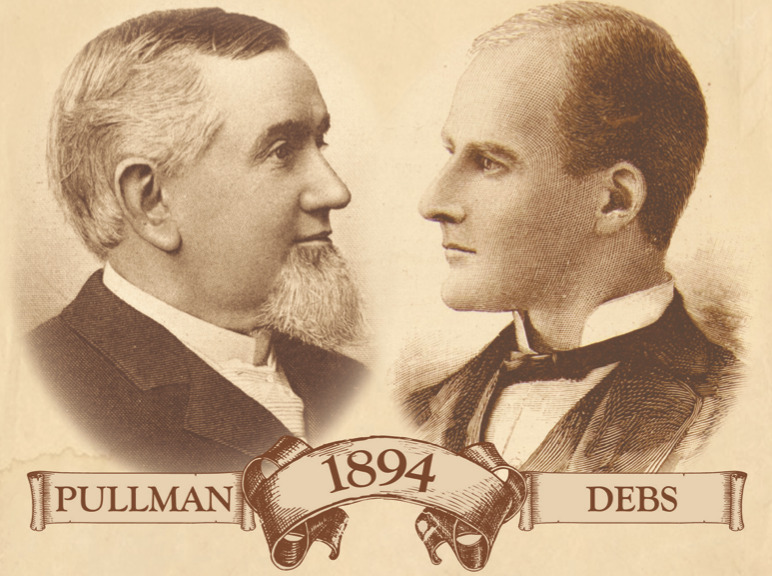

And George M. Pullman, of course. We don’t mention him much these days since the holiday is now used to celebrate seasonal change more than activity. But George has a major role in the day we use to mark the value of Labor, and it is worth a tip of the topper for his contribution. He was what was once called an “industrialist.” This is an archaic term for people who built companies that manufactured things useful in building a vast economy. The time for that harks back to the change of the previous century, the one the bounded into “The Twentieth Century.”

The world was in a bit of a tizzy then due to something they called “The Panic of 1893.” It has some echoes that are oddly familiar. In 1890, there had been a wheat crop failure not dissimilar to the one imposed by the current war in Ukraine. Speculations in South African and Australian properties collapsed, and there was a run on gold at the U.S. Treasury.

More echoes. In today’s international landscape, we have a new class of Industrialists who made their fortunes not by building things but by outsourcing the means of manufacturing to places overseas. Back in George M’s time, there was an economic depression that commenced in 1893. Trains were the means of transit across North America, and the economic activity that surrounded the various manifestations of that means of travel were a big deal.

George M. ran an enterprise called the “Pullman Palace Car Company,” describing in words the luxurious means of transcontinental travel that would continue until Dwight Eisenhower chartered our interstate highway system to support a different type of “car” based on the personal use of fossil-fuel powered personal cars.

George M. reacted to the economic disruption with a bold attack on his labor force. He was known to have a sharp eye for overhead costs, so he attacked one of the most visible of them: wages of the people who built his railroad cars. He cut the wages of his company’s workers by about 25 percent. He had a vulnerable target in his sights, since the workers lived in a real “company town” in which his company owned the homes that the workers rented. There were no reductions in rents or other charges in the town of Pullman, a modest residential area about a dozen miles from the downtown Chicago Loop.

You can imagine that put a bit of a damper on family budgets in Pullman, and those working families faced something that looked like real deprivation- or the sort of hunger that people are talking about this winter in places around the globe.

A delegation of people approached George M. to present their grievances about low wages, poor living conditions, and 16-hour workdays. George refused to meet with them and ordered them off the company payroll. That led to a strike vote and a walkout in May of 1894. The cascade of events from that action were dramatic. The Pullman Palace plant emptied and signs went up at the gates saying the facility was closed “until further notice.”

At the time, about a third of the Pullman work-force was represented by the American Railway Union (ARU), which was not technically a partisan in the company’s labor dispute but clearly had equities in both production and consumption of the product that rode the rails.

The ARU convention in June of 1894 brought the issue to national focus. It was depicted as an example of an abusive employer oppressing his laborers. Since the ARU was an indirect players in the dispute, a variety of creative and indirect actions were proposed to pressure George M., whose manufacturing workers did not actually work on the railroads. One was to unhitch Pullman-built cars from trains. Another was a union boycott of any train containing Pullman rolling stock to pressure the rail companies from doing business with George M.

That ripple effect turned into something we know now as “The Pullman Strike.” It brought to fame a labor-leader named Eugene Debs, who was instrumental in coordinating a strike action by railroad workers that shut down all rail lines west of Chicago. The strike had a direct effect on 29 railroads, mostly outside the West and Deep South areas and essentially shut down the nation’s transportation.

That consequence was effective but sparked anger that had the potential to slide into violence. Debs may have been pleased by the effectiveness of the boycott, but he was also alarmed by the anger expressed by the workers, which he feared could lead to violence. After a peaceful address by Debs in June of 1894 groups in the attending crowd rioted and derailed a locomotive hauling the US Mail.

That brought Washington into the affair as wildcat strikes spread across the state of Illinois. The Governor dispatched six companies of militia to clear the way for trains in Danville and Decatur, and Washington contributed a levy of Federal troops to be sent to Chicago under the provisions of the Sherman Antitrust and Interstate Commerce Acts.

That act raised the issue to national prominence and placed Gene Debs in an intractable position. He wanted to support peace even as the workers perceived the Federal troops as opposing their boycott. That turned the matter into one in which strikers were confronting Federal troops, and a mess that took weeks to resolve. The scope of the disturbance was remarkable, with a quarter million workers in 27 states involved. The mass media of the time, including a periodical called “Harper’s Weekly,” declared the nation was “fighting for its own existence just as truly as in suppressing the great rebellion.”

Terms change, of course, and Harper’s was referring to the Civil War, a horrific event then only thirty years in the past. But powerful currents had been unleashed by the ARU and Washington that prompted marches and demands for recognition of worker’s rights as well as demands that social unrest be repressed directly by Washington.

It is interesting that the tides of emotion are swirling again about oddly similar issues. The discord about Labor had largely subsided into an observation that work is generally a good thing even as we have a national celebration of taking a day off. We have changed modes of transportation, the automobile replacing the train as our national means of locomotion.

All that is likewise under assault, since we are told every few months that fossil fuel use will end our world any minute. We have transformed our communications technology from printing press to instant digital communications. The same issues, laid over new and not fully understood technology, have both echoes of the past and reverberations of something quite transformational.

Here at Refuge Farm, we embrace the day off. We took a poll and are generally of the opinion that we may get around to doing some work tomorrow. Maybe we will generate a piece about the value of labor. It sounds like it may take some effort, though, so we will take it slow just in case someone decides to send troops.

Where is Grover Cleveland and Gene Debs when you need them?

Copyright 2022 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com