Life & Island Times: Grands

Editor’s Note: We are in a curious time. There is War on the Continent unseen in generations.. Marlow contributes this note from the Coastal Empire to tell the tale of women who have lived in times of trouble and who gave us our lives.

– Vic

My grandmother on the German side of my family died in early February1987 at 84. Her obituary in the local Valley Stream, Long Island, newspaper said nothing of note about who she was or what she had endured, let alone the joys of her life. As her first grandchild, I got the chance to know who she really was — “grandma” but a whole lot more.

Funny, we never called her großmutter or oma — grandma in German. Her side of my father’s immediate family wanted to blend into America’s melting pot. My grandfather’s mother was altogether different and had me calling her urgroßmutter until my parents heard me mumble it one day and put a no-uncertain end to it.

This wrinkled, Coney Island roller coaster riding great grand was a mockingbird pip. Being from East Prussia, she despised Rooskis, calling them mudak. Both of those words got me in trouble, when I muttered them while watching nightly national TV news with my parents back home after returning home from a summer visit with the un-English speaking, Commie hating, American sympathizer side of the family.

As I grew older, I learned that the entire family tried to bear this last in mind, but it didn’t seem to prevent outraged slamming down of phones and raised voices. No one ever raised his or her voice in our family except at great grandma. She really knew how to do it.

When I shared with my buddies that I had an ancient relative teaching me cuss words, they all said she was fantastic. They wished they had great grandmothers like that. I have tried to bear that in mind with my grandchildren.

I inherited her mouth.

Grandma’s common sense and tolerance like her meals were beautiful, succinct, and complete. German food was something you only get to know when, after hating it and its blandness your entire childhood and thinking everything from the horseradish on all luncheon meat sandwiches to the divine Bavarian desserts were never without heart and soul in support of our human conditions. So, when she died, I found myself alone and cold in a strange place until I located some of her dishes’ component parts at the local Long Island delis like her slaw. I might have shriveled up and died otherwise.

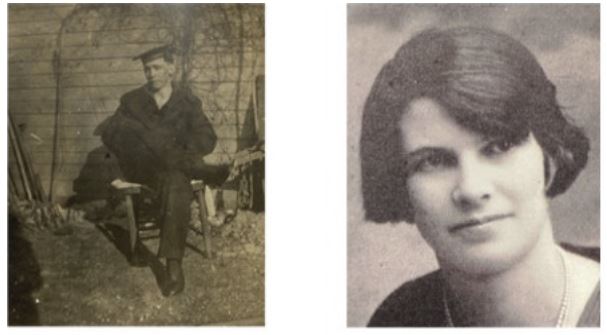

The vintage photographs of her as a young woman showed those empty eyes of various, silent-era, cowboy movie stars because the photographers hadn’t yet discovered how to make her hazel eyes visible or distinct in black and white photos. She once shared with me, when I was young, a photograph of her and grandpa she had hidden for almost four decades — her mother-in-law, the Commie hater, would have been enraged by the premarital scene’s hand holding in which they looked like a German prince and princess.

“You know when that was taken, Marlow?” she asked.

“When?”

“Otto and I were visiting each other at my cousin’s home — me from the family farm in upstate and him from Brooklyn. We quietly were planning our wedding despite not having announced the other’s presence in our lives to our families. (Authors note: It’s important to note that Grandma was Catholic and Bavarian, while her intended was raised Protestant by Prussians.) He had no money to support a family, since he worked as a driver for his father’s trucking business in the City. We’d be very poor to start. Then he told me that he got that day a raise with one day’s work now fetching $4.00. So, instead of buying food, I wanted our picture taken. This is the picture . . . it cost $4.00. We were beyond happy, and life was beautiful. Look, Marlow. Look.”

“Yes, grandma.”

This is still the most bohemian, romantic thing I could think of the two of them doing, before or since.

Another intriguing part of this conversation at that time was this aside “During his early life, your grandfather, Otto, was a soft spoken, hardworking, strong man who could be a kindly but unholy terror.”

I knew about the hardworking and strong parts but nothing about the terror ingredient that forever remained undetailed.

Later on, it explained a lot to me about my father and his upbringing.

Witty and droll, not so much. Self-teaching, laser focused, and entrepreneurial, indeed.

I hadn’t really known my German grands that much until that long ago, brief moment.

All I know now is that at my grandma’s request they spent what was then a week’s worth of pay on a photograph because they were so in love with each other.

———————————–

Initially walking around these remembered moments in a loose oval there was a feeling of hopelessness. I tried it clockwise and then counterclockwise. Forward. Then backward. I then decided to sit in our old, worn leather chair, reviewing. It was one of those “cold” Coastal Empire winter days — it was not supposed to get hotter than 52 degrees, the sky was gray with nights likely in the low 30s, and it might rain the next day, the blond pixie cut hairdo weather lady with the neck tattoos said excitedly that there was a chance of flurries. I’ve always suspected that locals’ longing for a winter rain was an undercurrent of desire for snow. When the weather is like this and the Empire’s smelling rain but hoping for snow, the past appeared clearly without so much of its original confusion, doubts and pleasure, and my days with grandmas surfaced.

It was during this brief moment that these grands started coming into focus and making a bit more sense.

Were they quite perfect because very little of them depended on artifice? Yes — they were the real deal . . .

Grandma battled lifelong melancholia aka depression. She always had this slightly magical air of tragedy beneath her carefulness, quiet grace, and charm where great grandma could be coarse, wry, funny, and sarcastic. Great grandma could be illusive and quick, while grandma was dark but strong. There was just a surface hint in grandma of great grandma’s open anarchy. And I, the prime ticket holder to the front row center seat to their grandma chorus and arts, would watch and appreciate and know. They had fans.

I figured out that my great grandma had added more than a pinch of spice and herbs to my sinister, lazy, and cynical sides, while my grandma contributed a cup’s worth of underlying passion for long, oh-what-the-hell, Hail Mary passes in my personal and professional lives. Neither of them watered down my pre-packaged dry mix. They came from different worlds but similar times of deadly authority where icy, serious things occurred, and explosive danger lurked. Despite their opposite ends of the continent and faith origins, they were senior members of the Ladies Auxiliary of the tough-as-iron men. Their eyes light has long ago gone out, passing by the bridges of the City’s boroughs, the Verrazano Narrows, passing Gibraltar and then the Alps northward perhaps back to Bavaria and the Memel River where their real lives, long ones, found their sources.

They had none of what I would see during the 60s of boomers’ luxuriously innocent corruption and nasally middle-class nonchalance. A decadence on the cheap if you will. They could not and would not ever afford themselves of obscure, jaded humor or waltzing to a different drummer. No enslavement by the hypnotic rhythms of rock and roll for them. Defined by their trying to survive the arbitrary tsunami rogue waves of historical levels of poverty and violence, complicated by the mechanics of war things completely and terminally altering their instincts that what had before been certain death that then surprisingly became for them this booming explosion of their grands and their unending processions of toys and play into their lives. They were unaltered but overjoyed. Like it or not, their very presence fortuitously introduced novices like us to the practice of instinct, of going beyond childish goofiness, until we could treat certain death with a silent coolness and calmly look over the situation and at our options.

As my reflective energies trailed off, it was raining and the kitchen scents of W’s homemade spätzle and beef rouladen made these grands briefly appear before me. They had avoided being trapped in prisons of their own or their times’ device. In the background of the cable music station’s jazz, I heard homeward bound cars on the wet street outside. These two carried on despite pain, not staying home but venturing forth not allowing the power of world’s tragedies to subdue them. They did the extinguishing of their dark skies and forecasts.

Lord, they were grand.

Otto and Irene — Marlow’s German grandparents 100+ years ago during and just after WW I

(the photo described above remains unlocated 35 years after her death and 63 years after she showed it to me)

Copyright 2022 My Aisle Seat

www.vicsocotra.com