Life & Island Times: Let’s Pretend We’re Invisible

Editor’s Note: Sorry for being out of touch. Kitchen reconstruction has been a continuing and irritating distraction- not to mention the Stupid Olympics that dragged me back to 1980 and the decades since to think about the years spent thinking about time in the Republic.

Here, and in the now, Leo and some extraordinary former Sandanistas and Puerto Rican Nationalists have had my (almost) complete attention these last few few weeks. I will do a story about it, eventually, with pictures, but I am going to have to get the grout dust and wallboard debris vacuumed up and the place cleaned up before I subject you to it. The quality of mercy is not strained, right?

Oh, for what it is worth, we had Union on the Big River back in the big dust-up, and he married his love in New Orleans as soon as it was safe to put your head up. We are River People, and above all, water people.

I have t tell you how viscerally this one from Marlow hit me. I love Key West. Life is short.

Live it.

– Vic

Let’s Pretend We’re Invisible

I first met Mike somewhere close to 13 years ago at the best Irish pub on the last coral island of the Florida Keys. He was one of the folks who labored at the US government’s secretive counter narcotics task force at the western end of the island. It was located in the building that housed the Fleet Sonar School when it taught Anti-Submarine Warfare to all of the east coast Navy types — surface, subsurface and airdales — spanning three wars from 1940 through 1974.

He was in many ways like a lot of the retired US Navy wayfarers who fetched up on this island’s shores during his fifties. Scarred, still full of piss and vinegar and badly twisted. Twenty plus years of seafaring would do that to you.

For a while neither one of us said much of anything other than maybe howyadoing or howzithanging. We just slouched there on worn wooden armchairs, or was it the rotating armed barstools, and relaxed on the bar’s back patio, while our favorite bartenders poured us large glasses of stout at discount prices. We just stared straight ahead, with no focus except for an occasional apparition of an ocean wave cresting as it rushed towards parallel rows of sand dunes in a light morning fog.

This large squadron of southbound American White Pelicans offshore finally left Key West after a prolonged layover. These almost dinosaur-looking birds are very shy of human contact and made queer antediluvian grunts when they took wing.

“Jesus,” I said. “Did you see all those white pelicans who’ve been hanging out off the US Navy housing beach at Truman Annex? I thought they never came near inhabited areas.”

“White pelicans?” he muttered, slouching down a bit further on his barstool while still staring intently into the patio’s cooling darkness.

“Yeah, just south and east of where your townhouse is on Truman Annex, where the old surface Navy’s officer club used to be . . . just offshore.” I said. “They’ve been hunkered down there for several weeks. Dozens and dozens of them. Yeah . . . like they were heading to Cuba but decided to stay ’cause they don’t like Castro and his weasly little brother.”

“What?” he said, still squinting into the darkness.

I noticed he had been consuming his glasses of the Irish near-black elixir fairly rapidly: First-Second-Third-Fourth and more. Up and down. Up and down. Up and down.

“You better slow down,” I said. “If we try to roll outta here with too much under our belts, we’ll roll ourselves straight into the county jail. These Monroe County mounty bastards love popping us Navy pukes and putting our DUI mugshots up on their website. I don’t have much to worry about, but your bosses will fold you up like a cheap British sports car u-joint.”

He continued to drink, albeit bit more slowly, as the conversation shifted aimlessly, he continued not meeting my gaze. The jukebox music was getting louder — some kind of pop song about lost love and driving homeward bound for days on end with no sleep. We could just barely hear each other.

The next thing I recall was the strong call of nature to drop off my rental beer. I headed off to find a empty urinal only to be joined by Mike two stalls over. While we both steadfastly stared into the wall in front of us, over the partitions he began to tell me his tale. And then later I him mine.

Many more stouts, ales and shots of whuskey have been consumed since then. That’s the way sailors and their stories are.

In the course of our apparently endless story telling during the next decade, we set up shop in various cigar bars, honky tonks and dive bars around town, as well as expanding our gathering to include two other Vietnam era squids. Down on their luck writers and traveling drug company sales persons seemed to gravitate to these places — for reasons I’d rather not think about right now — but they all had one thing in common: they encouraged with rare exception the telling of tall and secret tales from our pasts. You know . . . the ones that we swore sometimes by signature and others by oral oaths to the guilty that we would never divulge anything, proving the rule perhaps, that somethings must be told and retold in order for its memory to be preserved. But for whatever reason, they were almost always cozy, woodsy bars with big rooms and, most importantly, small spaces for private conversations, possessed of decent food, four hour long happy hours with locals discounts, and . . . yes . . . of course long histories of their own roguish memories.

But in truth it all started with was nothing more than a casual conversation between two people standing at adjoining urinals, trying to remain invisible from one another. I went in there to piss — not to talk to Mike. So, when I sensed him standing there, it was only natural to ask him what he did in the Navy.

We both were of Irish extraction. I soon found out that Mike’s stories were long winded, slowly told and at least to my ears perfectly understated.

He was hard of hearing in his right ear from his 50 cal machine gun tub, brown water Navy days in southeast Asian river deltas. As time drifted by, we four old farts would sit around for hours at various pubs, finally settling on the southernmost Legion post, while drinking excessively, swapping sea stories, but mostly listening to Mike’s descriptions of having to go over the side of the patrol river boat a mere several hundred yards downstream from a fire fight to unfoul the water drive intake and other such colorful “no-shitter” sea stories.

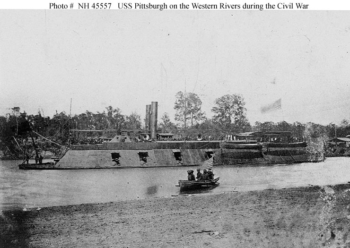

America’s brown water gunboats — Vietnam (l) and Civil War (r)

A long ago ancestor of another of us tale tellers had served on the Union Navy’s western river gunboats during the Civil War. He had read his great grand’s journals. There were more than just hints of the same in those old tales to the details of Mike’s stories — hours of dull cruising on rivers, examples of sheer folly from senior rear echelon leadership, utterly ridiculous happenings (e.g., entire trees falling across the boats while tied up at night), and moments of complete and utter chaos.

Mike told one story that was a dead ringer to a journal tale from the Civil War. Mike’s boat came around the bend in a small river tributary just outside a Viet Cong controlled village and surprising (and being surprised by . . . ) an entire rice field full of people. Mike’s description of people on both sides (US and Vietnamese) very slowly lowering themselves down out of sight and pretending that no one was there was almost a perfect replica of what the great grand had written in his journal.

Maybe it was the number of beers or the cheap, heavy-pour cocktails, but comparing the two experiences was not just eye-opening and chilling but soul searing when we realized that a sort of willful invisibility had made Mike;s presence in our foursome possible many decades later.

Even when pressed, Mike, just like that Civil War journal, could not account why these heavily armed parties did not fall to slaughtering each other. All that we could discern was that these combatants instantly saw everyone everywhere in those two distantly separated moments, and sheer belief in the other side’s belief — not the will to survive — to remain unseen prevailed. Perhaps as one of us remarked, it was a strange momentary darkness that simply prevented their discernment. Others might have called it a form of cowardice or the stain of original sin, but Mike felt like it maybe was a divine grace that had visited them in that brownish back water.

Copyright © 2018 From My Isle Seat

www.vicsocotra.com