Life & Island Times: Plague Chronicle Notes — Part XXIII — Crazy is Always an Option

Can we live without hope? Can we live without faith, tradition, family, ritual?

We are now learning during these plague days of street rage and jihad that we can live without all of these things, but only in a condition of a radical now — a barbarism that is enslaved to immediate sense impressions (hot social media video clips and breaking news audio takes) and sense gratification. My old age and Irish tinged optimism say this will never end our story, since something real and fresh gotta be deep in our hearts. Yet our hearts natural restlessness is peaking, chest pain emerging, mental fog increasing as our hearts look to find an anchor point.

Maybe a safe mooring is in our past?

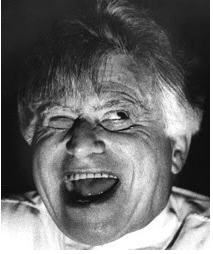

Six and seven years ago my parents passed. A bit more than a quarter century ago, my last grandparent, Otto, passed.

Otto, the first and only born child of East Prussian immigrants Henry and Olga, was born in 19th century just after his parents left their thatched hut in Memel (now Klaipėda in Lithuania) on the Baltic Sea coast.

That cottage stood until WW II.

His life in the new world began without electricity, running water, radio, or telephones, but with distant yet strong echoes of the famine and war years borne by elderly relatives and neighbors. Once when I was sitting at his hospice bedside, he suddenly arose from his semi-conscious state to open his eyes and said in a worried voice, “Is there a famine? If not, I’ll have a drink.” I had never heard him utter the word ‘famine’ before, so I assured him there was no fmine. “Not here, Pops, not now. Have a sip of my drink, since it’s the hospice’s Happy Hour and the cocktail cart has moved on.” He downed it, forcing me to chase the cart for another round for each of us.

Otto grew up in the most intense urban environment imaginable — Brooklyn NY — as an unchurched Protestant amidst a sea of immigrant Catholic Irish and Italians in the 19 aughts and teens. I loved hearing the stories from his mother and aunt of the old country and the (fill in the blank with the ever changing German curse word du jour) Russkies, the drunk singing sailors stumbling about the port city, dogs (Fraulein), the churned butter, the horses, and their life as wives of sailors. They lost their mother from a plague or flu when they were girls, increasing the burden on their father and them to keep the household together and running, while their father was out at sea. They also told me of new world stories how little Otto became toughened on the city streets as he walked home each day from public school through hoods of “Catlic tuffs.” Großmutter forced Otto’s pursuers to line up one day at their stoop and fight him one after the other. He beat the “crap out of all them Papists” (my latter-day sanitized translation of her profaner phrases at the time), one by one. That was when I learned how Otto came to be gifted many years later with his lifelong nickname “Sharkey” — after the Lithuanian heavy weight champion Jack Sharkey.

When WW I came and Otto joined the US Navy, he succeeded in rising to first class Machinist Mate in less than two years. They were immensely proud of that rare achievement, carrying with them a photo of their Sharkey with the senior enlisted man in the US Navy on the deck of Otto’s repair ship with the coast of France in the background. Now and then they would lapse into German as they remembered bad times of tensions with Prussia’s larger neighboring countries, but their memories were quirky, as all memories tend to be. One of their undiminished fears was seeking refuge from armed troops in the wheat fields around town’s outskirts

Then came America. Beautiful America. And Brooklyn. Big, Bad, Brooklyn.

Recounting of new world bad tales faded quickly as time passed, America and Americans prospered, and the good time stories commenced in earnest.

My grandfather was a man of immense strength, herculean work habits, passionate beliefs in fair play yet very fixed views of others not like him and his kind. Curiously, he married one of those other kinds — a Bavarian Catholic beauty and then chose to live just as the 1929 crash loomed with her and their two infant children in the distant Long Island burb of Valley Stream — far away from his disapproving mother and meddling aunt.

Yet, Brooklyn always held sway with me for my elder relatives’ foreign eccentricities were like being in a 19th century Dickens novella. Consequently, as the eldest great grandson, I got to visit and stay overnight with them as the neighborhood evolved in the 50s and early 60s. Those were great experiences that included sleeping in Greenlawn Cemetery on sweltering summer nights as my hosts had an in with the sexton.

It had its share of hardships as well. The old world of ethnic enclaves of Brooklyn, when the schools were filled by remarkable women and the churches were filled by tough men with good habits, was fading. Even our lovable Bums had left town.

One thing remained constant. As the neighborhood changed to become increasingly poorer, rougher and violent, Großmutter and Tanta Lena were still bug-eyed roller coaster riders at Coney Island. They were such regulars that they would ride for free all day long on their birthdays well into their 80s and 90s.

Their crazy was so well known that no one messed with them.

So, during these times of national tumult, it is this spirit that I wish to retain and expand during the years left to me — socially, politically, and personally.

To end this show let us sit down by the piano over in the corner and listen to it accompany an unseen singer belt out “Unchained Melody.” No arrangement and no microphone needed. This encore is not planned. Let’s join the singer as he belts out frighteningly ever stronger high notes. He like we may not have much left, but he’s not holding anything back, and taps into some unknown reserve of strength. Suddenly, we are no longer at death’s door. We’re once again the mythic ones of old — voices, hearts and minds, strong and full, eyes glistening with delight as we glance at one another as if to say, “We still got it, don’t we?”

Screw dying in bourgeois respectability. Thanks, America. Because even in our current decline we are something to behold in the raw joy of life.

Copyright © 2020 From My Isle Seat

http://www.vicsocotra.com