Melting Pot

So, if the American Melting Pot got melted and no longer works, it may be time to start wondering about what is coming next. We will be returning to The Grand Tour of Europe as a means of comparing and contrasting our befuddling times with those that have come before. It is a curious thing. Some of the oldest Americans in the family had arrived here in time to have families that contributed young men to The Revolution in 1776. Another wave arrived in time to fight on both sides of our Civil War. That is about where the family stands for immigration issues.

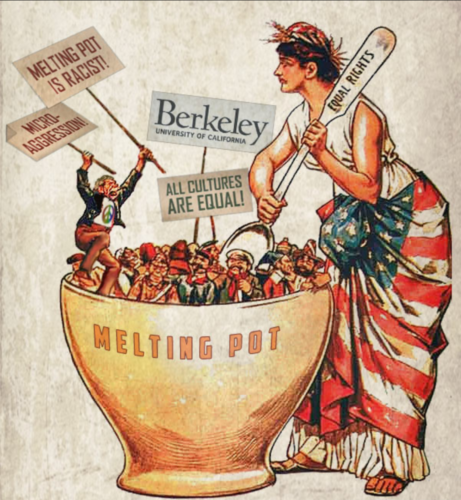

In terms of forensic groups, we are trained observers, of course. Or were, anyway. That is part of why this immigration issue is an emotional around the Circle of Salts. The word is that the old American tradition of the “Melting Pot” has passed away. We are not sure why the term ‘assimilation’ has become associated with another word with old connotations. The rhetoric surrounding our American union conveys the sense that we are all one people. There is even a Latin term for it: “E pluribus Unum.” From the many, one.

Like everything else, the concept has undergone some change. You might consider it another of those social inversions that are so popular. These days of identity politics might phrase the old words with a different emphasis. From One, there are Many. And none of them seem to get along very well.

My younger boy once had a paper due in his college history class. The assignment was to provide a survey of physical migration in American history, specifically during the early decades of the 20th Century when our hometown of Detroit assumed some of its current manifestations. His professor had given out a Compact Disc (anyone remember what those were?) with 15,000 interactive sources, a thick textbook and a strict mandate to utilize both. The topic of the paper was to be about the 1920s and the American urban migration.

Talk on The Patio veered from the America of the Founders, dedicated and educated, to the Socotra and various Celtic and Italian bloodlines represented around the circle. The Irish Diaspora had always appealed to us, but the paper was limited to Italians, Poles and African-Americans. By geography, the migration patterns reflect the south-to-north movement to Chicago or Detroit. My son allowed as how he could use some help, and we arranged for another session on Friday night. The rest of the week we rolled the concept around in our collective mind as we went about our sundry affairs in the Imperial city.

Business tugged us back to the urban landscape. There was an advanced project that popped up as a business opportunity, and overseas there was a sensitive matter that had to be handled with some delicacy. Like events today, we had to divide attention between crisis items. We reviewed the CD and looked at the material. There was some Langston Hughes poetry form the Harlem renaissance, and a manual from the Ku Klux Klan. There were source documents outlining the theories of Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois.

There was this picture of Dodge Main Assembly Plant on Joseph Campau Street in Detroit. We put the advanced network material aside, hypnotized by the soaring smokestack.

Chicago was the more interesting of the towns to study, just as it is this morning. The problems of civic life actually reflect the consequences of policy. The streets reflect an increase in criminal behavior across the spectrum of behavior with the impct of the passage of time. Chicago still exists. Detroit of that day has vanished. Having seen the very last of of it as a child, as a functioning city, gave it a certain doomed fascination.

This is interesting in the context of “melting pots,” since Detroit once was proudly independent and known for its distinct ethnic neighborhoods, thirty or forty of them that formed a crazy-quilt east and west of the River, and out Woodward Avenue to the northwest where the rich lived. Only Poletown and Greektown remain of them, cut off by the concrete rivers of the Interstates.

The Poles were fiercely committed to their institutions because in America, they were in effect emancipated. In pre-World War I German-occupied Poland, Poles were stripped of their land, which was handed over to German immigrants. In Czarist Russian-occupied Poland, Poles were legally prohibited from owning land at all.

Consequently, Polish-Americans attached great status to home ownership, and as powerful as that motivation was, an even more powerful attraction to their Catholic faith made them erect great churches in the middle of their neighborhoods, a powerful social magnet. Detroit once boasted more owner-occupied homes than any other city.

The third biggest conglomeration of Polish Americans is in Detroit, Michigan. The largest remaining Polish district is called Hamtramck, on the East Side, on Joseph Campau Street.

The pictures from the CD illustrated neighborhoods clustered around the churches, in the shadow of the first Ford Plant at Highland Park, and the enormous Dodge Plant on the East Side. It is now the stronghold of sitting members of the United States Congress who answer the calls to prayer five times per day in accordance with their Faith.

Hamtramck is the township and it outdates the state of Michigan. Established in 1798, it was a township in the Northwest Territory named after Revolutionary War Colonel of German-French heritage. His name was Jean Francois Hamtramck and representative of the original French-Canadian population. Hamtramck maintained that character until it was re-organized as a village in 1901 with an increasing population of Poles.

Detroit is two cities. The original French trading center was oriented on the river. When the Americans came to the old Northwest they brought the strict township grid system of hot-south squares. The French streets jam at angles into the English squares, and contributed to an ability to get lost downtown every time we ventured down there.

John R and Beaubian Streets are not places for a suburban kid to be lost in the shiny borrowed family car, but that is how we first learned our French geography. The junction of the old river city and the ordered squares made no sense. But there were things to look at then, and much of the city remained in those days, though the old neighborhoods had largely emptied out near the downtown.

The riverfront farming towns changed dramatically after the turn of the last century, and Hamtramck was briefly the fastest-growing community in the nation as the population soared between 1910-20, reflecting the Boom brought by War in Europe and the booming new auto industry. The Dodge Brothers opened the Dodge Main plant adjacent to Hamtramck, and it eventually expanded to include 5 million square feet of workspace.

Between 1914 and 1920, Hamtramck’s population swelled from 3,589 to 45,615, in part because of the large influx of newly arrived Poles. By 1930, about 85 percent of the city’s 56,000 residents were of Polish extraction, and the community-which measures just over 2 square miles-was the most densely populated city in the United States. Today, about half of Hamtramck’s 22,976 residents claim some Polish ancestry.

Detroit was already the machine capital of America when the Poles began to flood in. They settled in Hamtramck, which was physically isolated from Detroit by the Grand Trunk Western Railway to the east, and the factories to the south.

Beginning in the 1870’s, another river of immigration began to flow toward Detroit. The agricultural economy of the American South had become unstable.

The Depression of 1873 devastated Southern planters. Cotton prices fell by more than a half, from 15-cents a pound to seven. The ailing Southern agricultural system that was further disrupted in 1915 by floods and the boll weevil infestation that destroyed the cotton crop in the fields. Increased mechanization of farms displaced many African Americans, and they made their way to the cities in two streams.

One flowed north along the Mississippi River to Chicago, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Gary, Indiana. These migrants were originally from Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas. The eastern current followed the railroad lines northward along the Atlantic coast to New York and Philadelphia from Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina, and Florida.

A huge demand for labor developed with the onset of the war in Europe. In order to increase factory output, northern industrialists actively recruited people of color. These agents promised employment and supplied them with free railroad transportation.

The exodus of agriculture labor infuriated southern property owners just as it did ancient Pharaoh. One of the functions of the Ku Klux Klan was to organize and manage the wave violence to keep them in line. In December, 1916, one thousand Negroes gathered at the Macon, Georgia, railroad station. They wanted to board trains, but instead they were dispersed by the police. Other southern communities stopped trains and prohibited the sale of railroad tickets.

Emigration from the eleven states of the old Confederacy skyrocketed from 207,000 in 1900-1910 to 478,000 from 1910-1920. Nearly 800,000 left during the 1920’s and almost 400,000 during the Depression of the 1930’s. Once lines of contact were established between families and friends in these northern cities movement became easier, just as it did with the Polish communities in America and the Old Country.

When they got to Detroit, African Americans were restricted to an area near the downtown called either “Paradise Valley” or “Black Bottom,” It was an area on the near east side of downtown, bounded by St. Antoine, Hastings, Brush, John R, Gratiot, Vernor, Madison, Beacon, Elmwood, Larned and Lafayette Streets. The 1910 census reported that the “Negro” population was 5,741 and owned 25 places of business. But the African-American community grew quickly as the city’s booming auto industry attracted a flood of workers from around the nation and the world.

By 1920, the time of the exploding Polish population, African-Americans owned 350 businesses in Detroit, including a movie theater, the only black-owned pawn shop in the United States, a co-op grocery and a bank.

World War Two brought another tidal wave of African- American immigration to work in the plants. Even as World War II was transforming Detroit into the Arsenal of Democracy, cultural and social upheavals brought about by the need for workers in the bustling factories threatened to turn the city into a domestic battleground.

The new war factories, like the Willow Run bomber plant, attracted so many workers that it was impossible to house them all. Not only was housing inadequate, but the entire infrastructure was pressed to near bursting. Transportation, schools and recreational facilities were jammed, and there were lines for everything. Rationing made gas scarce and, and there were fights at the grocery stores, lines for the buses, and even newsstands were the site of conflict over the classified ads offering rooms for rent.

Projects were thrown up to accommodate the demand. One of them was intended for African-Americans, and named for Sojourner Truth, the famous conductor of the Underground Railway. Its location near a white neighborhood sparked Detroit’s first significant race riot in 1943. It would not be the last.

In the 1960s, activist/comedian Dick Gregory quipped: “In the South, whites don’t care how close Negroes get, just as long as they don’t get too big. In the North, whites don’t care how big Negroes get, just as long as they don’t get too close.” His observation fits the reality of the changing city of the 1950s. The population of Detroit was transforming. Waves of blockbusting changed neighborhoods over night, as cynical real estate developers moved African American families into white neighborhoods, charging them premium prices, and then buying out the fleeing whites at bargain basement rates.

The shift in demographics was not visible until the disastrous civil uprising in 1967, when outrage against the brutal tactics of the largely white Detroit Police on Twelfth Street brought on five days of rioting that left 43 dead. The remaining white population of the city fled to the suburbs, either east to the Grosse Points, or northwest to Royal Oak and Birmingham and Bloomfield Hills. With the election of Coleman Young, Detroit became an overwhelmingly African-American city.

The loss of the tax base after the riots killed the place. Schools and services disintegrated, and they stopped cutting the grass along the interstates.

My family was part of the flight. I was born in Mount Carmel Hospital. Doctor Doerr presiding, and was taken to the family home at 14897 Sussex Street. We moved to 14230 Kentucky Street shortly thereafter, just off 6 Mile. The folks had arrived in town in 1949, hearing that there were jobs in the automobile business. They stayed in the suburbs first, in a town called Birmingham. They rented rooms from a Miss Guezzey, and then shared a place with their friends the Veryzers in Ferndale.

The town was starting to hum again on the construction of civilian goods after war production ended. The first house I remember was the one on Kentucky Street, near the D&W Oil Company.

Then the neighborhood began to change and we left. Dad said he had a really good year, with a hefty bonus, and cleared $14,000 dollars income. That was the ticket out.

Hamtramck stood with Greektown as the remaining ethnic enclave. The construction of I-75 to the east of the neighborhood completed the moats around the area, and the Poles hung on. Where there is value and community, people will stay put. The migration of the manufacturing jobs away will inevitably weaken the foundation of a community based on home-ownership and church.

Some of the Poles are still there, but there has been another migrational pattern, Hamtramck has attracted new immigrants, especially from Yemen, Bangladesh and Pakistan. Hamtramck became the first Muslim-majority American city in 2013. Two years later, it became the first to have a Muslim-majority city council with four of the six council members being Muslim. In November 2021, Hamtramck’s city council and mayor were elected to unify Hamtramck under a civic government of one Faith.

That comes with a cost, of course. The recent Gaza troubles have emphasized a lingering problem with anti-semitism. But we will see how that works out over time. There was enthusiasm about the first municipality in the United States to be governed entirely by Muslim-Americans. But in September 2023 the social wars erupted as Hamtramck drew attention for it’s refusal to fly the Rainbow Flag and perceived homophobia. We will see how that turns out, since things could still melt together or cool and fragment.

Detroit may be a place we can see if the word “assimilation” still means something that brings us together. In a few words, “E pluribus Unum,” you know? There are only three words, you know?

Copyright 2023 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com