Mutiny in Paradise

(Laura Beach on Eniwetok, Marshall Islands. Photo Wiki)

By mid-morning on the 4th of April, 1946, we had channel fever and decided that the threat posed by a gigantic rogue wave- a tsunami- had passed.

We entered the lagoon at Eniwetok Atoll under tow via the deep-water channel north of Parry Island. We were sporting a rakish seven-degree list to port and poor Nagato looked quite the worse for wear.

It was a relief to drop the anchor and secure the deck department for some much needed rest as we prepared to have workboats alongside to begin emergency pumping. We had hundreds of tons of seawater in compartments fore and aft; the former had flooded due to existing battle damage, and the latter a product of the counter-flooding aft we had to do to maintain steerage.

It was a relief to have a chance to relax a bit and look around. The Crossroads tests were scheduled for July, and with much fanfare, but I considered we would be ready in plenty of time to make our appointment with the atom bombs. We had several pleasant uneventful weeks there. On board we patched up boilers; the sailors went ashore and I spent most of my time with fins and a mask, exploring the coral reefs. Eniwetok Atoll, for which the whole aggregation of 40 islands is named, is home to 850 native Marshall Islanders.

In terms of land area, the whole sprawling chain is only a couple square miles of dry land in toto, and no part of it is more than fifteen feet in elevation. We were only about 190 nautical miles from our destination at Bikini, which had been selected as the optimal location for the Operation Crossroads Atomic test series for which Nagato was going to play a starring role.

We were determined to make it under our own power, and in watching the Bo’sun forge the deck department into a can-do unit, I was confident we could do it, if we could have a few weeks to pump out and conduct some basic repairs to the boilers and take on a reliable quantity of diesel fuel.

The atoll had a curious history. It had passed from Spanish to German control by the time of the First War, and was occupied by the Empire of Japan with the rest of the Marshalls in 1914. That possession was formalized by the League of Nations in 1920, and administered as the Japanese South Pacific Mandate. As part of the buildup for the Pacific War, the Japs built an airfield on Engebi Island, which they used as an emergency strip to refuel planes flying between the big naval complex at Truk and the islands to the east.

Eniwetok was reinforced in 1944 with a few thousand troops from the Imperial Army’s 1st Amphibious Brigade, which had served in China. The Japs were not able to complete their defensive works on the beaches, and were not ready for the five-day American invasion in February of 1944. Most of the major combat occurred on Engebi Islet, the most important Japanese installation on the atoll. Combat also occurred on the main islet of Eniwetok itself and on Parry Island, where the Japanese had constructed a seaplane base.

Following its capture, the anchorage at Eniwetok became a major forward Fleet operating base as we leap-frogged toward the Philippines. We avoided the still-occupied Japanese islands, cutting them off and letting their garrisons starve. When the atoll was a going logistics concern, in July of 1944, the daily average number of ships in the lagoon was 488. That shows you what the impact of war production was, since that number is a hundred more than there were ships in the entire Fleet in 1941.

The total tumbled as the war swept west and north, and now there was a curious sense of abandonment. There were Quonset huts to accommodate the throngs of sailors and airmen who had been here in 1944, and now the runways, repair shops fuel farms, hardstands, hospitals, marine railway and floating pipeline gave the place an eerie sense of abandonment. Only a token garrison on Eniwetok was left, and the outlying facilities were left just as they were in 1945.

The natives seemed phlegmatic about the amazing storm that had passed over and through them. In several instances bunkers and the like were now used as sheds and pigsties, and larger structures, such as air command centers or ammunitions depots, were used for human habitation. The Japanese radio-direction finding and command building on Taroa Island was being used to hold worship services, a holy purpose for a structure built as part of the war machine of the Empire of the Sun.

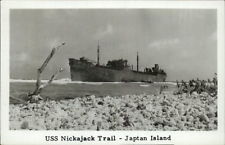

Our former companion-ship Sakawa had arrived long before we did, and as our crew cycled ashore, we began to hear just how bad the blood was between our two ships. The actual events of the cruise south from Yokosuka had been curiously inverted. In one version of the sea-story on Eniwetok, it was Sakawa who had come to the assistance of Nagato, and valiantly had attempted to rescue her senior (and much larger) partner. We discovered that a Liberty Ship tanker, the Nickajack Trail, had been diverted to bring us fuel while we were adrift and dead in the water, but had run aground in bad weather and been lost.

Sakawa had something else we did not have: eleven of her former Japanese officers aboard to assist the American crew. I don’t know if some of the Japanese pride had affected them, but there were obviously some significant morale problems that did not affect the pirate crew of our battleship.

It is often said that the United States Navy has never had a mutiny, and since Sakawa had no standing on anyone’s naval register, that may still be true. But we did discover at Eniwetok that it was not for lack of trying. The story emerged that five of the ship’s American sailors were angry over the dismal working conditions aboard Sakawa. In a ship normally staffed by over 730 men, the Navy had assigned a crew of only 165. Nagato only had 180, but the enormous amount of work required by all hands just made us more determined.

Not so on Sakawa. The five sailors decided that they were not going to Bikini, or anywhere else, and removed the pressure line to the over-speed trip valves in the fuel system to sabotage the ship, and then poured sand into the oil and water pumps. They smashed gauges, tachometers, and cut high -pressure steam lines in an attempt to get relieved of duty aboard the bedraggled cruiser.

Rather than being relieved of duty, the five sailors were brought up on charges. I credit Captain Whipple’s steady, firm leadership for the lack of such profound discipline problems on his battleship.

After three weeks of repairs on Eniwetok, flooded compartments pumped out and repairs performed on the most critical machinery, we were ready to depart for Bikini and Nagato’s last mission. As we made got underway on our own power on the 25th of April, we discovered that the old lady seemed to want to show her stuff for this final sprint. The great monster managed to cruise at 13 knots, the best speed we ever got out of her.

We made the trip alone without any help and managed to drop the anchor at our assigned spot all by ourselves. We made it in two days, down to one serviceable boiler, but she answered all bells right until we made fast to our assigned buoy.

Sakawa did not make it to Bikini Atoll until May. In addition to repairing the sabotaged machinery, they had to take time for five individual Captain’s Masts.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303