Naval Architecture

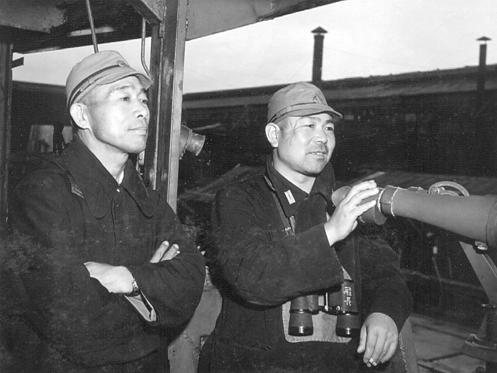

(Two members of Nagato’s original crew. All Photos USN courtesy Lyle Hansen).

Lieutenant Commander Ed Gilfillen confessed to being a little disoriented by the way the Japanese ran their ships of war. He said that:

“The design of USN ships were shot through with definite principles, all born of experience and most have the force of an article of faith. We American sailors like clean lines. No matter how useful a ladder, a pad eye, an anchor platform or bearing for an outboard davit might be, we cannot have them. We hoard space and weight with single-minded intensity. If a pump can be made a little smaller or lighter by using alloy steel bearings and supplying the highest-grade lubricating oil under pressure, we do it.

Around the guns we allow exactly enough space to protect the men from the recoil- not an inch more. Cleanliness aboard our ships matches that of hospitals If that requires a clean sweep-down six times a day and a quarter of the crew busy chipping pain, no matter. By which is called “preventative maintenance,” we keep our ships always in fighting condition, It is a way of thought which has produced the most effective ships in existence, and which won the war in the Pacific.

Japanese practice is different, or at least it was before the Imperial fleet was reduced to Nagato alone. This ship was roomy, to a degree, even in the turrets. Machinery was simple, rugged and large, made of easily-obtainable materials with plenty of room around it to maneuver. There was no such thing as preventive maintenance. Engines were designed to operate a long time without repair and then to be replaced inn a Navy shipyard. The crew was there to fight, not to clean ship; every aspect of their lives focused on the single issue of battle. This is in marked contrast to our way of doing business, which was to keep the ship squared away and ready for action.

(Member of Prize crew checks a flooded compartment, 1946).

Other navies of the world operate closer to the Japanese principles than to those of the Us Navy. The war has just proved that our way is superior. Whether it will continue to be best in the face of new developments seems problematical.

During the July air raids of 1945, Nagato was hit on the port anchor chain, losing the anchor and holing the bow just above the water line. The patch placed over this rent in the hull was going to give us trouble later. Another large bomb entered the superstructure just under the catapult deck, exploding on the face of the Number 5 barbette, on which it etched a mark that resembled a rising sun, The face of the steel was left smooth at the point of impact. From there out the metal was spattered and gouged in outward as though a firecracker has exploded on softened butter. The interior of the barbette was quite uninjured- the face of the turret was protected by nearly a foot of armor steel.

(Nagato’s Movie Theater).

The space around the barbette had been cluttered with ventilating shafts, bulkheads, and other impediments, but all of there were carried away by the blast that also bulged the deck over it upward. The result was to form a large hall, partially open to the weather where we later showed the movies. At sea, waves sometimes burst in through the shattered bulkhead, swishing and gurgling through the chair legs as the movie-goers raised their feet out of the water without taking their eyes off the action on the screen.

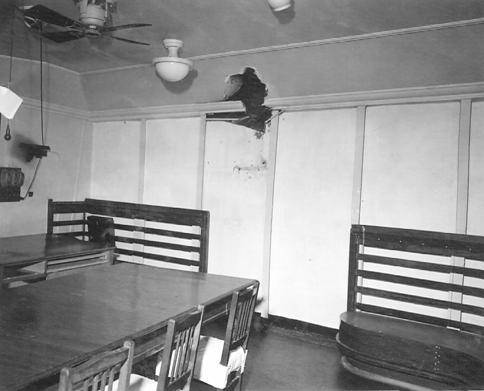

(The Wardroom entry wound).

Some sort of projectile traveling upward entered the wardroom to port and went out to starboard without detonating. I don’t know whether anyone was in the compartment at the time, but there were marks on the table that might have been made by teeth. I have no idea what it might have been.

The gross detail of the engineering equipment and spaces of Nagato were obvious enough, and conventional in appearance, but the piping and trunk system was so complex that we were never able to use it with any certainty. All about the deck, and below, were hand wheels to open and close valves. The problem for us was that in most cases, the valve was not co-located with the wheel. The turning force from the wheel was transmitted through Rube Goldberg-style reach rods to the actual valve. These in turn were routed right through bulkheads and inaccessible spaces. To have traced them all would have been a prohibitive effort and we did not bother.

Some were important, though, and we had to investigate by direct observation, sometimes helped by Japanese inscriptions, sometimes by experiment to see what happened when we turned them. We managed to identify some of the more important valves, but there was always an element of doubt.

One night in Yokosuka, the petty officer of the watch noticed that the end of the accommodation ladder had sunk underwater. He took a sailor’s fatalistic view of that and joisted it out, but when it went under again he thought it worthwhile to call the Command Duty Officer. Investigation revealed what had occurred. A visitor to the quarterdeck had turned a hand-wheel on deck out of idle curiosity and had managed to flood the Number 3 Magazine!

We scrambled around and has to bring a tug alongside the mooring to pump it out again. I always had the feeling that some of the crew knew far more about the valves than the officers did.

In fact, several times I seemed to hear a disgruntled sailor mutter: “I know just where that valve is!”

They could have sunk the ship at any time without risk of being identified and court-marshaled. All I knew was that sailors are sailors the world over, and many of our guys thought the war was over and wanted to go home, not steam a Japanese battlewagon to the Marshall Islands to blow it up with an atom bomb.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303