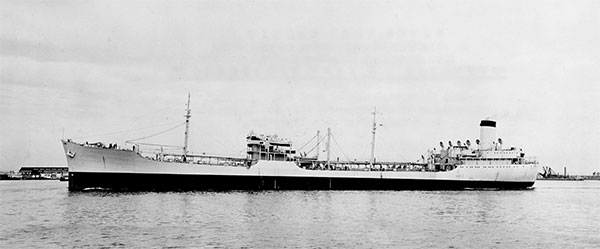

Neosho

(Cimmarron-class fleet oiler Neosho (AO-23) during her fitting out in New Jersey in 1939. Photo USN).

Yesterday I celebrated the extraordinary career of ADM Noel Gayler, Naval Aviator extraordinaire and hero of the Battle of the Coral Sea, a tactical draw between the navies that saved Australia from the predations of the Empire of the sun. Naval Aviators get a lot of ink- they earned it. I grew up in a household headed by one, and heard it all. But that was not anything like the whole story.

USS Neosho (AO-23) was a Cimmarron-class fleet oiler, second ship to be named for the Neosho River that flows through Kansas and Oklahoma. She was new construction (1939) and known affectionately to her crew as “The Fat Lady” for her beamy aspect and ungainly sea-keeping.

She and her crew had been in Hawaii and survived the attack on Pearl, and was one of the high-value units of the American fleet. A mobile gas station to keep the carriers stocked with fuel and aviation gas was absolutely vital to successful operations. She was at the Coral Sea when the Japanese arrived. The significance of their advance was that the Dominions of Australia and New Zealand were at risk of being cut off, at a minimum, and invasion was a strong possibility.

At all costs, the sea-lanes to the Dominions had to be kept open, and they had to be protected against attack and possible amphibious assault.

As the American and Japanese fleets sought each other out on 6 May 1942, Neosho refueled the carrier Yorktown and the heavy cruiser Astoria, and then retired from the carrier force with a lone escort, the destroyer USS Sims.

While independently steaming, Neosho was spotted at 1000 on 07 May by Japanese search planes and misidentified as a carrier with her escort. 78 aircraft from the carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku were scrambled to search the area in vain for an American flat-top. Despite the high-value nature of her vital capabilities, Neosho was not what they were looking for. Eventually they abandoned the search for combatants, and returned to sink Sims and hit Neosho seven times, leaving her adrift and ablaze.

One Japanese pilot, his Val bomber disabled by Neosho’s guns, rode it down into the target, an early example of the Kamikaze tactic that later ravaged the Americans at Okinawa.

(Last known picture of Neosho after the attack. Photo IJN).

Panic was an understandable result of the encounter, and the close-aboard explosion and sinking of the Sims. Neosho’s condition was dire. Captain Phillips sent word from the bridge to his XO, LCDR Firth: “Make preparations for abandoning ship and stand by.”

Firth had been injured during the attack and was fading in and out of consciousness. Seeing the loss of their escort, some of the sailors began jumping over the side and floundered in the five-foot seas that pummeled the hulk.

On the bridge, Captain Phillips called the communications officer and ordered him to destroy all classified material, particularly Neosho’s code books. The compromise of that material would have been disastrous. Seeing that crucial step in the abandon ship drill, sailors on the bridge deserted their stations, shouting that it was “every man for himself.” The officer of the deck, who was also the navigation officer, was among those who panicked. He left the bridge after he heard the captain give the order to flood the ship’s magazines.

Forward, men were throwing the life rafts overboard, and leaping after them. The Navigator warned them that they risked losing the rafts. Other men were trying to launch the Number 1 motor whale boat, and he ordered a life raft moved so it could be swung out. Thinking twice about his actions, he then headed back for the bridge, but as he moved up, he heard more men coming down, crying “every man for himself” and rushing to throw themselves into the water. The Navigator then leaped into the water, along with the enlisted men, as the radio officer and several others tried desperately to launch another boat.

Seeing officers abandoning ship, the men lost all discipline. In a few minutes, the water and the rafts were filled with escaping seamen, who were certain the Neosho’s end had come. That was the crucial moment in the disaster.

With heroic effort, Philips and his crew- the part that had stayed with her, anyway- managed to keep her afloat until the American destroyer Henley found them on 11 May 1942. After transferring the survivors aboard, she sank Neosho with gunfire. What the Japanese could not do, we had to do for her.

The rescued men of Neosho and Sims now safe onboard the Henley said an emotional goodbye to their ship and watched it slip beneath the waves.

But there was the matter of the men who had abandoned ship immediately after the attack. Their rafts had been dispersed by wind and sea and were no longer in sight. Henley set a course that would follow the apparent drift track of Neosho in reverse, in an effort to find them.

The search went on for three days, but she found nothing, and eventually Henley set a course for Brisbane to land the survivors.

As that search went on, the men aboard the rafts were dying. It had been a week already drifting at sea. What supplies they had were quickly consumed without stiff rationing. Men dying of thirst drank seawater, and died more quickly. Sailors fought over what food there was, and the officers failed to impose discipline to preserve what there was.

As Henley returned the bulk of the survivors to Australia, the destroyer Helm was directed to sortie from Noumea to continue the search. Three days out, Helm came upon four rafts lashed together bobbing on the waves. Four men were alive on these rafts, all that remained of the 68 who had been on them when they abandoned ship. Of the nearly one hundred others who had been on single rafts, no trace was ever found.

There was talk of an official investigation into the conduct of those who had abandoned ship, but Higher authority felt it best not to stir up new problems. Neosho was lost, and assigning blame to anyone but the Japanese would only bring bad blood between professional line officers and naval reservists, since all the officers who abandoned ship were both reservists and dead. Actually, in these early days of war such events were only to be expected. There was no time for niceties.

At Coral Sea, the carrier Lexington had been lost, and Yorktown needed repairs. The Japanese were on the march again, this time headed for an unknown target in the mid-Pacific. In the Dungeon at Pearl, Joe Rocherfort’s code-breakers Jasper Holmes, assisted by ENS Mac Showers, on the job for almost two and a half months, were in the process of unraveling the identity of the target as the Neosho’s crew drifted.

The Battle of Midway was just a month away.

So the matter of Neosho’s crew was dropped.

Copyright 2017 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

A full account of the loss of USS Neosho is described in the book, Blue Skies and Blood by Edward P. Hoyt.