Old News

We started into a discussion of some old institutions founded in the wake of old scandals the other day. The Editorial Staff was reluctant at first, since it was old news on a gray day that displayed the earth’s reluctance to commit full-blown to Spring. The Staff is committed to the season, though, and the younger members unfamiliar with archaic terms like “the 1934 Act,” or “Watergate.”

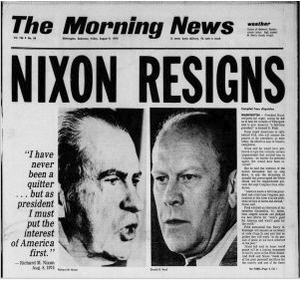

After a quick review, the reaction was pretty cool. Some muttered that “if that sort of stuff went down and got cleaned up, why are we doing all this again?” The older members at the table, representing two of the more popular current genders, recalled the dashing performance of attorney John Dean, and the presence of his lovely wife Maureen in the gallery illuminated by the klieg lights. Richard Nixon, the president at the time, was a suitable villain in the piece, dark-jowled and frowning at the intrusive cast of investigators, including media sensations Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

Watergate was awesome. It had everything. The narrative featured an evil President, accusations of widespread misconduct, a certain amount of sex and a lot of money. The thing went on for a while, picking apart a cover-up of criminal activity that ranged to the very top of the American political food chain. The burglaries at the Watergate- there were two- and the cover-up of both caused a cascade of action.

In Congress, there were the Church and Pike Committees. Both featured disclosures of unethical activity by people in the agencies, and which produced an impressive list of recommendations to ensure the government did not become involved in supporting unlawful acts in the Executive Branch. More impressive was the jail time awarded to the participants.

Sixty-nine indictments were filed against Nixon Administration officials, including Attorney General John Mitchell, and recently deceased G-Man Gordon Liddy. Forty-eight were convicted for clandestine or illegal activities, which freed us from government abuse of public and personal privacy matters. The suffix “Gate” was subsequently appended to any emerging public scandal or controversy. It keeps the original matter current regardless of circumstance.

Our recent scandal, given much shorter shrift, was an amazing two-year investigation played out over five in sensational media coverage. RussiaGate was trumpeted as a massive collusion of domestic political activity with post-Communist Russia. It shared a theme with the original Gate, which was misbehavior of a Chief Executive. His conduct threatened the overturn of the U.S. Government in the interests of foreign powers. There was furtive movement around the table due to short attention span or inadvertent delirium.

Editor-in-Chief Socotra noted the actual probe was focused by an elite team of legal experts selected by veteran Washington insider Robert Mueller, supported by the FBI. His team labored mightily for two years, spending nearly $40 million taxpayer dollars, and produced incontrovertible evidence that Russia’s government enjoyed screwing around with the American electoral process. As did the Americans who began interfering with other nation’s elections shortly after the conclusion of the Second World War.

As a box score, the Mueller Investigation resulted in a number of indictments which in totowas respectable enough to be compared with the long-ago Watergate affair. Mueller and his team of prosecutors indicted 34 individuals and three Russian businesses on charges ranging from computer hacking to conspiracy and financial crimes. It sounds big and serious, but all but a handful of these were Russian nationals working in a “troll farm” or other cyber operations alleged to have penetrated the Democratic National Committee and disseminated internal documents to WikiLeaks. None of these individuals were subject to U.S. jurisdiction, of course, since they never were in the United States nor willing to come here to face charges.

The ten big ones nailed were not government officials at the time, with the exception of a single individual unwise enough to have been named as Mr. Trump’s National Security Advisor. They were:

Paul Manafort, Rick Gates, Konstantin Kilimnik, Roger Stone, George Papadapolous, Carter Page, Alex van der Zwaan, Richard Pinedo and retired Army Lt. General Michael Flynn. Another, cited previously, was a relatively junior FBI lawyer.

The members at the table were clearly losing track. Some asserted that there was a curious difference between how the two scandals unfolded. None of the RussiaGate offenders were officials in the government, with the exception of General Flynn, and he was in his first weeks returning to an official position. Manafort, Gates and Stone were- are- grifters, who used their connections to enrich themselves and their associates.

Stone, a high profile private actor, was born a year after I was. It is a known age for possible resistance to even a certified legal letter. He was deemed such a threat of risk-of-flight that 32 heavily-armed special agents were dispatched before dawn, backed by a CNN breaking news team, to arrest him at his home. It was great theater. Page was a CIA source at the time, a fact not disclosed to the FISA court by FBI attorney Kevin Clinesmith. The surveillance of Page served to open the entire Trump campaign and surprising transition team to detailed surveillance, as did warnings that Papadapoulus had a few drinks overseas and confided that the Russians might have had something on the Clinton campaign. Michael Flynn was already a figure of note to the FBI for his disavowal of Administration policy when he was Director of the DIA, and failure to register as a foreign consultant. Like many in Washington.

Day drinking was not yet prohibited on the Socotra Publishing premises when the Mueller testimony to Congress was rolled out. It was much appreciated in bringing clarity and closure to the long investigation. In his remarks, Mr. Mueller asserted he was not aware of the political lobbying firm “FusionGPS,” the group that provided the spectacular Steel Dossier, a largely fake disinformation paper provided by the Russians to cast colorful aspersions on the conduct of then-real estate mogul Donald Trump.

In amplification of the detailed investigative process, the COVID pandemic provided new tools for information gathering. Office and home delivery services of potable alcohol enabled intense conversations on veracity and credibility of the various information sources. In Watergate, government officials were justly prosecuted for criminal behavior. In RussiaGate, private citizens were prosecuted for becoming inconvenient obstacles to the efficient transition of one administration to the next preferred by the government.

It was sort of interesting. The staff, now mostly sober by circumstance, supported the Old News of the Watergate investigation fully. That was easy. By a vocal majority, it appeared to believe the orchestration of government power against partisan opponents was abhorrent. The subsequent discussion of the role of Government using its inherent powers against partisan opponents was judged to be sort of a strange inversion of ancient reporting. Thankfully, during a vigorous exchange regarding the 2019 Department of Justice IG report of serious violations of FBI procedures and due process the doorbell rang.

Someone had broken the code to what helps old news stay fresh. It is part of the ethos that keeps the Staff abreast of new news. That led directly to an affirmation of the “deliver direct to the conference room” policy of Uptown Spirits, an unofficial and somewhat detached contributor to the editorial production process. The Board agreed that some factors suggest the times have changed.

For example, during Watergate, there were no legal home or office deliveries of bonded liquor. Uptown now provides a legal means by which old can become new, without benefit of car keys. Their large selection of popular spirits and hard-to-find liquors in support of corporate decision making is innovative and forthright. We note that Delta Airlines and Coca-Cola are already onboard.

Whether we are looking for whiskey, tequila, cognac, rum or vodkas, they have us covered for the specific hours most effective for the production process. And at the conclusion of the much more jovial meeting, we agreed that everything was fine and we could talk about the 1934 Act at a later meeting, with the stipulation that nothing be carried concealed, bottle or not. But there was general agreement that maybe we could cut back on the social media thing. Someone might be listening.

Copyright 2021 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com